When the French and Indian War finally ended in 1763, no British subject on either side of the Atlantic could have foreseen the coming conflicts between the parent country and its North American colonies. Even so, the seeds of these conflicts were planted during, and as a result of, this war. The French and Indian War, known in Europe as the Seven Years’ War, was a global conflict. Even though Great Britain defeated France and its allies, the victory came at great cost. In January 1763, Great Britain’s national debt was more than 122 million pounds, an enormous sum for the time. Interest on the debt was more than 4.4 million pounds a year. Figuring out how to pay the interest alone absorbed the attention of the King and his ministers.

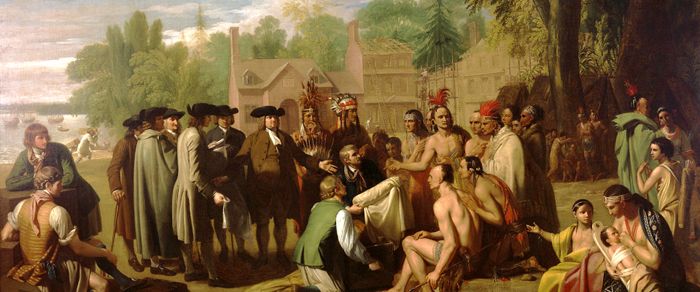

Nor was the problem of the imperial debt the only one facing British leaders in the wake of the Seven Years’ War. Maintaining order in America was a significant challenge. Even with Britain’s acquisition of Canada from France, the prospects of peaceful relations with the Indian tribes were not good. As a result, the British decided to keep a standing army in America. This decision would lead to a variety of problems with the colonists. In addition, an Indian uprising on the Ohio frontier–Pontiac’s Rebellion–led to the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade colonial settlement west of the Allegany Mountains. This, too, would lead to conflicts with land-hungry settlers and land speculators like George Washington.

British leaders also felt the need to tighten control over their empire. To be sure, laws regulating imperial trade and navigation had been on the books for generations, but American colonists were notorious for evading these regulations. They were even known to have traded with the French during the recently ended war. From the British point of view, it was only right that American colonists should pay their fair share of the costs for their own defense. If additional revenue could also be realized through stricter control of navigation and trade, so much the better. Thus the British began their attempts to reform the imperial system.

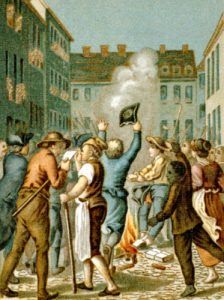

In 1764, Parliament enacted the Sugar Act, an attempt to raise revenue in the colonies through a tax on molasses. Although this tax had been on the books since the 1730s, smuggling and laxity of enforcement had blunted its sting. Now, however, the tax was to be enforced. An outcry arose from those affected, and colonists implemented several effective protest measures that centered around boycotting British goods. Then in 1765, Parliament enacted the Stamp Act, which placed taxes on paper, playing cards, and every legal document created in the colonies. Since this tax affected virtually everyone and extended British taxes to domestically produced and consumed goods, the reaction in the colonies was pervasive. The Stamp Act crisis was the first of many that would occur over the next decade and a half.

Even after the repeal of the Stamp Act, many colonists still had grievances with British colonial policies. For example, the Mutiny Act of 1765 required colonial assemblies to house and supply British soldiers. Many colonists objected to the presence of a “standing army” in the colonies. Many also objected to being required to provide housing and supplies, which looked like another attempt to tax them without their consent, even though disguised. Several colonial assemblies refused to vote the mandated supplies. The British then disbanded the New York Assembly in 1767 to make an example of it. Many non-New Yorkers resented this action, seeing rightly that their own assembly could also be shut down.

The Stamp Act had led Americans to ask fundamental questions about the relationship between their local, colonial, legislatures, which were elected bodies, and the British Parliament, in which Americans had no elected representation. Many colonists began to assert that only an elected legislative body held legitimate powers of taxation. The British countered that, even in England, many people could not vote for delegates to Parliament but all English subjects enjoyed “virtual representation” in a Parliament that considered the interests of everyone when formulating policy. Americans found “virtual representation” distasteful, in part because they had elected their domestic legislators for more than a century.

In 1767, Parliament also enacted the Townshend Duties, taxes on paper, paints, glass, and tea, goods imported into the colonies from Britain. Since these taxes were levied on imports, the British thought of them as “external” taxes rather than internal taxes such as the Stamp tax. The colonists failed to understand the difference between external and internal taxes. In principle, most Americans admitted a British right to impose duties intended to regulate colonial trade; after 1765, however, they denied Parliament’s power to tax for the purpose of raising funds or raising revenue. Again, they saw the purpose of the Townshend Duties as raising revenue in America without the taxpayers’ consent.

The British also established a board of customs commissioners, whose purpose was to stop colonial smuggling and the rampant corruption of local officials who were often complicit in such illegal trade. The board was quite effective, particularly in Boston, its seat. Little wonder then that Boston merchants were angry about the new controls and helped organize a boycott of goods subject to the Townshend Duties. In 1768, Philadelphia and New York joined the boycott. As the boycott spread, harassment of customs commissioners grew apace, especially in Boston.

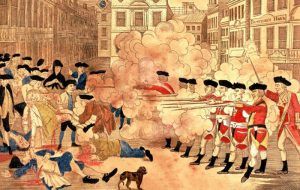

As a result, the British posted four regiments of troops in Boston. The presence of British regular troops was a constant reminder of the colonists’ subservience to the crown. Since they were poorly paid, the troops took jobs in their off-duty hours, thus competing with the city’s working class for jobs. The two groups often clashed in the streets. In March 1770, just when Parliament decided to repeal the Townshend Duties (on everything except tea) but before word of the repeal reached the colonies, the troops and Boston workers again clashed. This time, however, five Bostonians were killed and another dozen or so were wounded. Almost certainly the “Boston Massacre,” as colonists called the episode, was the result of confusion and panic by all involved. Even so, local leaders quickly publicized the incident as a symbol of British oppression and brutality.

Overall, American revolutionaries viewed English actions from 1767-1772 with suspicion. They read in British policy a systematic conspiracy against their liberties. As the colonists saw it, tax revenues fed corrupt British officials who used monies they coerced from the colonies to line their pockets, hire additional tax collectors, and pay mercenaries to come to America and complete the process of “enslaving” colonists.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander, updated April 2019.

Also See:

Heroes and Patriots of America

Initial Battles for Independence

Source: Library of Congress