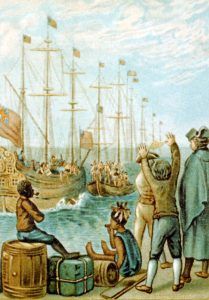

Boston Tea Party by D. Berger

The Boston Tea Party stands out as one of the defining moments in the annals of American history. After the imposition of unwanted, and, to their mind, unfair taxes on imported tea, dissident-minded Bostonians snuck aboard an East India Company ship disguised as Mohawk warriors and jettisoned the “noxious weed” into the Boston Harbor. While this story has become the stuff of legend in the United States, Boston was not the only city, nor was it the first, to oppose the importation of highly taxed tea. Charleston, South Carolina, or, as it was known in the eighteenth century, “Charlestown,” became the first colonial port to oppose Britain’s new tea policy. The events that transpired in Charleston Harbor between the winters of 1773 and 1774 have become known as the Charleston Tea Parties.

December 1773: The First Charleston Tea Party

Nine days before the famed overboarding of tea in Massachusetts, the artisans and planters of the Low Country staged their own act of rebellion. While the first of Charleston’s three tea parties was a bit of an anti-climax compared to that staged by their Bostonian cousins, it still made it into the record books as the first ‘tea party’ in American history.

On December 1, 1773, an East India Company ship named the London sailed into harbor carrying 257 chests of tea. This in itself was not unusual, Charleston was one of the colonies’ largest ports, and by far the biggest port in the South. But, in the weeks leading up the London’s arrival, Charleston’s papers had been fuming over the latest taxes imposed by Parliament. Calling it an “unconstitutional tax,” the South-Carolina Gazette told the citizens of Charleston how the British government sought “to raise a revenue, out of your pockets, against your consent – and to render assemblies of your representatives totally useless.”

With a fire now lit under them, albeit a contained one, the people of Charleston refused to allow the tea to be brought to shore. For two days, the London sat in the city’s harbor while its leaders decided what to do. On December 3, the city held a meeting, organized by Christopher Gadsen, a leading man in South Carolina, and the Sons of Liberty, in the Old Exchange building, space typically reserved for doing business. Charlestonians ranted about how “it would be criminal tamely to give up any of our essential rights as British subjects, and involve our posterity in a state better than slavery.” While the irony of slaveholders making such a proclamation seems to have been lost on them, the meeting prompted the townsfolk to action.

Charleston Exchange Building by G. Barnard 1865

Those in attendance decided to boycott the importation of tea. Despite this decision, Gadsen and the city’s other leaders still had to convince Charleston’s merchants, who would stand to lose a good bit of money on the deal, to join them. It took three weeks, but ultimately the Patriots won out, and a tea boycott began. Though, as we said a few paragraphs ago, it turned out to be rather anticlimactic. Rather than throwing the tea into the Charleston Harbor, the boycotters unloaded the tea and stored it in the Exchange building.

July 1774: The Second Charleston Tea Party

While Charleston’s first tea party proved an anticlimax, its second reached a fever pitch. In late June 1774, Charleston got word that the British merchant ship Magna Carta was headed its way. After reaching Charleston harbor on July 18, its captain, Richard Maitland, registered three crates of tea with the city’s royal customs office. Upon hearing of this, the city’s representatives, also known as the General Committee, called Maitland in to explain his “conduct” which was “contrary to the sense of this Colony in particular, and of America in general.”

According to Mailtand’s testimony, he had had no knowledge of the tea’s presence aboard his ship until he had set sail and had time to look over the wares stored below deck. Whether Maitland’s tea was truly a managerial oversight or just a quickly improvised lie to keep Charlestonians’ tempers at bay, the General Committee believed him. To his credit, Maitland quickly realized the potential lion’s den into which he had stepped and offered to throw the tea “into the river at his own cost.”

On July 19, the day after Maitland’s arrival in the Low Country, the General Committee and other Charlestonians gathered at the harbor to watch Maitland destroy his cargo as promised. But, Mailtand’s attempts to quell the anger of the onlooking South Carolinians hit a snag in the form of imperial red tape. When he went to the customs office and “tendered the duty in money” that he owed for importing the tea, the royal officials refused the transaction.

The Committee members were upset and they quickly took bureaucratic action. These well-to-do Charlestonians created a second committee “to desire the merchants not to ship or receive any goods in any bottom, wherein Captain Maitland was, or should be concerned.” The rest of the city’s residents took a different tact.

Charleston, South Carolina

Throughout the rest of the day, as word of Maitland’s failure to destroy his cargo spread, “the folks call’d Patriots” worked themselves up into a lather. That night, a mob of “several hundred men” went to the Magna Carta looking for Maitland, and “intended [to lay] hands” on the poor fellow. When they reached the area of the wharf where the vessel sat anchored, they clamored over its sides, bringing pitch tar and feathers in tow. Their intentions were clear: they wanted to tar and feather the man who had brought the unwanted tea into their city. This was a clear departure from the city’s other attempts at peaceful demonstration, as tar and feathering was an extremely painful, scarring, and potentially deadly process. Indeed, one eyewitness noted that “it is generally thought that if [Maitland] had fallen into their hands, it would have cost his life.”

Fortunately for Captain Maitland, it’s relatively easy to spot an angry mob numbering in the hundreds. Before his would-be torturers could lay hands on him, he quickly abandoned ship and headed for another British vessel nearby, the Britannia. While Maitland had escaped the mob’s fury, the angry Charlestonians found one full chest and two half-full chests of tea on the Magna Carta, which they took, with surprising politeness, to the Exchange building once again.

November 1774: Charleston’s Third and Final Tea Party

HMS Britannia in Charleston Harbor, painting by George Hyde Chambers, 1834

It did not take long for the Britannia, the ship that provided a safe haven for Maitland, to return to Charleston’s waters. Four months after it had escorted the erstwhile captain for the Magna Carta back to London, it reappeared in Charleston Harbor carrying seven crates of tea.

The General Committee seemed flabbergasted that their message had yet to get through to the shippers in London. So, as they were wont to do, they summoned the captain of the Britannia, Samuel Ball, Jr. to explain himself. Just as Maitland had done, Ball deferred responsibility for the presence of the “ the mischievous Drug ” aboard his ship. According to reports from the South-Carolina Gazette, Ball claimed that “ he was an entire Stranger to [the tea] being on board his Ship, ‘till he was ready to clear out when he discovered that his Mate had received [the chests] in his Absence. … That, as soon as he made the Discovery, he did all in his power to get them relanded, but all his Endeavours, for two Days together, proving ineffectual.”

If throwing his subordinates under the bus wasn’t enough, Ball also presented evidence that muddied the truth of his narrative. When meeting with the General Committee, Ball produced a document that had been notarized before he left London which stated he had no responsibility for the tea aboard his ship. According to the Gazette, Ball hoped this would “acquit him from the Suspicion of having any Design to act contrary to the Sense of the People here, or the Voice of all America.”

Despite the contradictory nature of Ball’s testimony that he did not know of the tea’s presence on the Britannia before he was at sea and unable to dock anywhere to remove it and that he had gone through the trouble of going to a notary before leaving London to create a document that said the tea wasn’t his, the Committee bought it – or at least they went with it.

The blame, instead, fell on three Charleston importers, Robert Lindsay, Zephaniah Kinsley, and Robert Mackenzie. Interestingly, there were no threats of violence by locals like there had been in July. Rather, the three merchants simply carried the crates down to Charleston Harbor and dumped the tea in the water. As reported by the South-Carolina Gazette :

“On Thursday at Noon, an Oblation was made to Neptune of the said seven chests of Tea, by Messrs. Lindsay, Kinsley, and Mackenzie themselves; who going on board the Ship in Stream, with their own Hands respectively stove the Chests belong to each, and emptied their Contents into the River… in View of the whole General Committee on the Shore besides numerous Concourse of People, who gave three hearty Cheers after the emptying of each Chest, and immediately after separated as if nothing had happened.”

And so the Charleston Tea Party came to an end.

©Jordan Baker, for Legends Of America, March 2021.

About the Author: Jordan Baker holds a BA and MA in History from North Carolina State University. A lover of all things historical, he concentrates his research and writing on the history of the Atlantic World. He also blogs about history at eastindiabloggingco.com .

Also See:

Samuel Adams and the Boston Tea Party