The Pawnee, sometimes called Paneassa, historically lived along the Platte River in what is now Nebraska. The name is probably derived from the word “parika,” meaning “horn,” a term used to designate the peculiar manner of dressing the scalp-lock, by which the hair was stiffened with paint and fat and made to stand erect and curved like a horn. The Pawnee called themselves Chahiksichahiks, meaning “men of men.”

Descended from Caddoan linguistic stock, the Pawnee were unlike most Plains Indians as their villages tended to be permanent. Initially, they were agricultural, growing maize, beans, pumpkins, and squash. With the coming of the horse, they did begin to hunt buffalo, but it always remained secondary to agriculture.

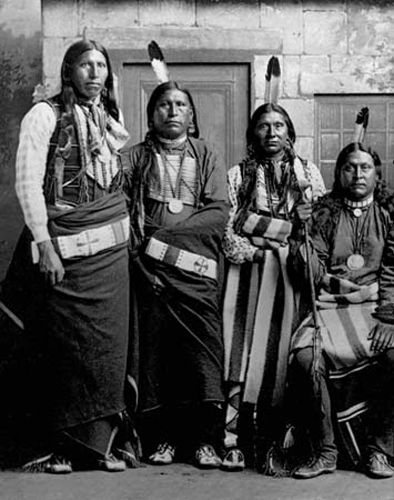

The Pawnee Confederacy was divided into the following four bands:

- Chaui – Grand

- Kitkehaki – Republican Pawnee

- Pitahauerat – Tapage Pawnee

- Skidi – Loup or Wolf Pawnee

The Chaui are generally recognized as the leading band. However, each band was autonomous, seeing to its own until outside pressures from the Europeans and neighboring tribes saw the Pawnee drawing closer together.

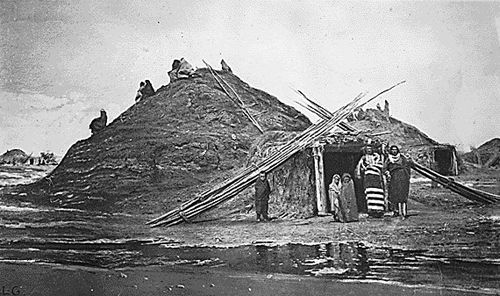

Living in large oval lodges formed of posts, willow branches, grass, and earth, as many as 30-50 people would live in the same lodge. Each village would consist of about 10-15 lodges.

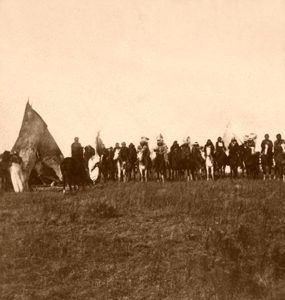

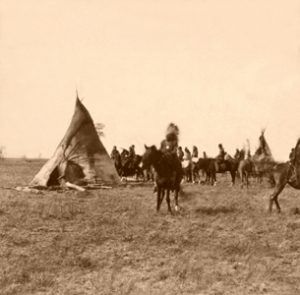

Twice a year, the tribe went on a buffalo hunt, and on their return, the inhabitants of the lodges would often move into another lodge. However, they generally remained within the village. The Pawnee were a matriarchal people with descent recognized through the mother. When a young couple married, they traditionally moved into the bride’s parents’ lodge. Women were active in political life, although men would take decision-making responsibilities.

The Pawnee were spiritual people, placing great significance on Sacred Bundles, which formed the basis of many religious ceremonies, maintaining the balance of nature and the relationship with the gods and spirits. The Pawnee were not followers of the Sun Dance, although they did fall victim to the Ghost Dance phenomenon of the 1890s. They equated the stars with the gods and planted their crops according to the position of the stars. Like many tribal units, they sacrificed maize and other crops.

There are also references to human sacrifice until the mid-18th century, when a book refers to a Lakota captive tied to a tree and shot with arrows. She was thought to be the last human sacrifice performed by the Pawnee.

The first European to see a Pawnee was Francisco Vásquez de Coronado while visiting the neighboring Wichita Indians in 1541. He encountered a Pawnee chief from Harahey, located north of Kansas or Nebraska. Little more is known about the Pawnee until the 17th and 18th centuries, when successive expeditions of Spanish, French, and English settlers attempted to enlarge their territory. At this time, Pawnee hunters first saw horses racing back to camp, eager to describe the tall, bizarre “man-beasts” they had seen—creatures with four legs, long tails, hairy faces, and clothing that gleamed like the sun on the water.

While expanding their territories, the first Europeans traded with the Pawnees in present-day Kansas and Nebraska, and the various Pawnee bands established loyalties to the different colonial powers according to each band’s best interest.

By the early 19th century, the Pawnee were thought to have numbered between 10,000 and 12,000. In 1818, the Pawnee agreed to the first in a long series of treaties that would eventually culminate in land cessions and placement of the Pawnee on Nebraska reservations in 1857 and Indian Territory (Oklahoma) in 1875. Despite governmental control of the reservations, the Pawnee tried to maintain their tribal structure and traditions.

Many Pawnee men joined the U.S. cavalry as scouts rather than face life on the reservations and the inevitable loss of their freedom and culture. By 1900, Christianity had replaced the Pawnee’s older religion, and smallpox, cholera, warfare, and devastating reservation conditions had reduced their number to only about 600.

The Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936 established the Pawnee Business Council, the Nasharo (Chiefs) Council, a tribal constitution, bylaws, and a charter. An out-of-court settlement in 1964 awarded the Pawnee Nation $7,316,096.55 for undervalued ceded land from the previous century.

Today, the Pawnee still celebrate their culture and meet twice a year for the inter-tribal gathering with their kinsmen, the Wichita Indians. A four-day Pawnee Indian Veterans Homecoming & Powwow is held in Pawnee, Oklahoma, each July. Many Pawnee return to their traditional lands to visit relatives, display at craft shows, and participate in powwows. As of 2002, there are approximately 2,500 Pawnee, most of them located in Pawnee County, Oklahoma.

More Information:

Pawnee Tribe

881 Little Dee Drive

P.O. Box 470

Pawnee, OK 74058

918-762-3621

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2025.

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

See Sources.