“Far away in northwestern Montana, hidden from view by clustering mountain peaks, lies an unmapped corner — the Crown of the Continent.”

— George Bird Grinnell

Glacier National Park in Montana, “America’s Switzerland,” covers almost 1,600 square miles filled with pristine forests, alpine meadows, rugged mountains, waterfalls, and spectacular lakes. Here may be seen, in all the majesty of their rock-bound settings, the remnants of the massive ice sheets that played a big part in shaping the surface of the earth millions of years ago. Not one or two, but 25 of them are clinging to the sides and ridges of the Continental Divide. Within the park are more rugged mountain peaks, glaciers, picturesque lakes, streams, and waterfalls than anywhere else in America in so condensed an area.

Within the park, physical evidence of human use dates back more than 10,000 years, when Native American tribes utilized the area for hunting, fishing, ceremonies, and gathering plants and berries. When the first white explorers began arriving in the region, the Blackfeet controlled the prairies on the east side of Glacier, while the Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai lived on the more forested west side. The Indians also traveled east of the mountains to hunt buffalo.

These indigenous people left a lasting impression of their occupation of this region, as the names of many of the mountains, lakes, and waterfalls still bear the original Indian names, such as Rising Wolf, Going-to-the-Sun and Almost-a-Dog Mountains, Morning Eagle Falls, and Two Medicine Lakes. They also contributed to the mysticism and romance of the country through the tales of their early day ceremonies in the walled-in valleys, their hunting exploits on the prairies, and the religious significance they attach to several of the high peaks. During these years, when their hunting grounds extended from the Missouri River on the south to the Saskatchewan River in Canada, this region was known to them as the “Land of Shining Mountains.” The Blackfeet considered the bold, grey perpendicular peak of Chief Mountain sacred because, according to the legend of the old Medicine Men, this was “where the Great Spirit lived when he made the world.”

The Kootenai Indians call Lake McDonald “The Place Where They Dance.” Since time immemorial, the Kootenai had returned to the foot of the lake to dance and sing songs. Here, they received help and guidance from different spirits.

White trappers’ exploration of the area began in the late 1700s, and by the turn of the century, French, English, and Spanish trappers searched for beaver and other pelts. They also traded with the local tribal communities. In 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition came within 50 miles of the park’s area.

The name “Lake McDonald” most likely derives from that of a Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader, Duncan McDonald. On one occasion, McDonald was on an expedition to the east side of the mountains when his scouts warned him of a Blackfeet war party waiting in ambush in the mountain pass. The party turned back and camped at a beautiful lake, and McDonald carved his name on one of the giant cedar trees there. When his name was later found, the lake was named after him.

“The sun set gloriously behind the Chief Mountain just as I would have given anything for one half-hour’s longer light. I was, most probably, the only white man that had ever been there.”

— Captain John Palliser, August 8, 1858

By the time the Civil War began in 1861, the mountainous region of Glacier had been “discovered” and explored. Fur trappers had crossed these mountains, and some continued to live nearby; missionaries had visited the region; a major American railroad survey scouted possible routes through the area; a British survey team skirted the region; attempts were made to pacify the nearby Indians, and two official boundary survey teams came to mark the boundary line. However, their collective impact upon Glacier was negligible, for the Blackfeet continued to dominate the region until the 1870s, deterring any influx of settlers or any other travel through the mountain passes.

The Blackfeet Indians continued to dominate the region until the 1870s. However, white settlers soon started to take a foothold in the area as more significant interest in exploring and exploiting resources increased. After the Civil War, men came in greater numbers to prospect for minerals, hunt for animals, establish homesteads, and develop businesses. With them, they brought intentions of acquisition and exploitation and a desire for economic gain. As the Indians’ resources were depleted, the tribes eventually signed treaties that would increasingly confine them to reservations and leave them dependent on the U.S. government. Today, the 1.5-million-acre Blackfeet Reservation adjoins the park’s east side, while the Salish and Kootenai reservation, encompassing 1.3 million acres, is located southwest of Glacier, mainly along the Flathead River.

The Great Northern Railway completed the first railroad tracks over Marias Pass in 1891, increasing the number of people in the area. They came to trap, establish homesteads, prospect, or enjoy the scenery. Soon, several small towns developed.

The first buildings constructed in the area were homestead cabins, but early visitors and residents soon realized the tourism opportunities. By 1892, settlers Milo Apgar and Charlie Howe offered rental cabins, meals, pack horses, guided tours, and boat trips for visitors who arrived in Belton on the Great Northern Railway. Frank Geduhn offered cabins and services at the head of the lake.

At this time, the west entrance to what is now Glacier was shrouded and tree-lined with towering, ancient western red cedars. After visitors arrived by train at Belton, they were rowed across the Middle Fork until a bridge was built in 1897. From there, they would ride in a stagecoach along a rugged dirt road connecting the river to Lake McDonald’s foot, where guests would board George Snyder’s steamboat for the eight-mile trip up the lake to the Snyder Hotel. It took most of the day to reach the hotel if all the equipment ran smoothly. After a night at the hotel, visitors could ride horseback into the mountains.

Miners also came searching for copper and gold. Under pressure from miners, the U.S. government acquired the mountains east of the Continental Divide from the Blackfeet in 1895. The mining towns of St. Mary and Altyn were within the present-day boundaries of the park when copper was booming in Butte and Anaconda, Montana. Though the miners hoped to strike it rich, no large copper or gold deposits were ever located. Although the mining boom lasted only a few years, abandoned mine shafts are still found in several places in the park.

Around the turn of the century, people started to look at the land differently. Rather than just seeing the minerals they could mine or land to settle on, they started to recognize the value of its spectacular scenic beauty. The area that would become Glacier National Park first received protection from Congress as a forest preserve in 1900 but was still open to mining and homesteading. In the meantime, people like George Bird Grinnell, an anthropologist, historian, and naturalist, and Great Northern Railway president Louis Hill, were pushing for the creation of a national park. In 1910, President Taft signed the bill establishing Glacier as the country’s 10th national park.

Afterward, the growing staff of park rangers needed housing and offices to help protect the new park, and the increasing number of park visitors required roads, trails, and lodging facilities. The Great Northern Railway built a series of hotels and small backcountry chalets throughout the park. These facilities were built in a Swiss style with characteristics like gabled roofs, exposed beams, ornate decorative moldings, balconies, and plenty of large windows. Three of these historic hotels continue to operate today, including the Glacier Park Lodge, built in 1912-13; the Lake McDonald Lodge, built in 1913-14; and the Many Glacier Hotel, built in 1914-15. The backcountry Granite Park Chalet, built in 1914 and 1915, also provides overnight accommodations.

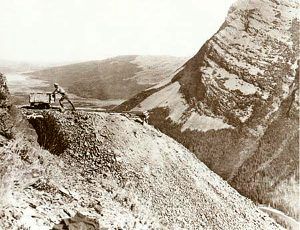

Eventually, the demand for a road across the mountains led to the building of the Going-to-the-Sun Road. The road construction was a considerable undertaking, and the final section over Logan Pass wasn’t completed until 1932, after 11 years of work. Today, the road is considered an engineering feat and was a National Historic Landmark in 1997. It is one of the most scenic roads in North America. The road’s construction forever changed how visitors would experience Glacier National Park, as visitors could drive over sections of the park that previously had taken days of horseback riding to see.

When the park was established, an existing wagon road up the North Fork became the park’s western boundary. This placed 44 homesteads east of the new boundary within the park. This area had long attracted pioneers due to its abundant wildlife, minerals, timber, fresh water, and the potential of coal and oil. The earlier arrival of the Great Northern Railway provided people living as settlers of the North Fork Valley with resources to sell to a national market. Though the homesteaders retained their private ownership of their lands, new park rules restricted hunting, trapping, and logging, and the private landowners felt that the National Park Service had an unofficial policy of trying to extinguish private property titles.

In 1912, every homesteader on the east side of the river signed a petition requesting that the North Fork Valley be removed from the park’s boundaries. The petition stated, “We submit that it is more important to furnish homes to a land-hungry people than to lock the land up as a rich man’s playground.” Park Superintendent Logan responded, “Instead of giving up any land there, I think we should take steps to obtain more land; in fact, get rid of every settler on the North Fork of the Flathead River.”

After the Half Moon fire of 1929, Congress appropriated nearly $200,000 to acquire private property within Glacier National Park’s boundary and began buying private landowners out. The National Park Service received another Congressional appropriation for land acquisition in the 1950s to acquire more private property. By 1954, no year-round residents lived on the east side of the North Fork Valley.

Just across the border, in Canada, is Waterton Lakes National Park. In 1931, members of the Rotary Clubs of Alberta and Montana suggested joining the two parks as a symbol of the peace and friendship between our two countries. In 1932, the United States and Canadian governments voted to designate the parks as Waterton Glacier International Peace Park, the world’s first. More recently, the parks have received two other international honors. The parks are both Biosphere Reserves and were jointly made a World Heritage Site in 1995.

The Glacier National Park features 185 mountains, 25 glaciers, 762 lakes, over 700 miles of trails, three visitor centers, and 13 drive-in campgrounds. People enjoy hiking, fishing, boating, wildlife viewing, horseback riding, guided tours, and more here. Historically, the park has six National Historic Landmarks, including the Going-to-the-Sun Road, Sperry Chalet, Granite Park Chalet, Two Medicine Camp Store, Many Glacier Hotel, and the Lake McDonald Lodge. Additionally, 358 historic structures are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Some of the most popular places in the park include:

Lake McDonald Valley – The hub of activity on the west side of Glacier National Park, this area was once occupied by massive glaciers that carved this area thousands of years ago. The valley is filled with spectacular sights, hiking trails, diverse species of plants and animals, historic chalets, and the grand Lake McDonald Lodge. Lake McDonald, at ten miles long and nearly 500 feet deep, is the largest lake in the park. High peaks surrounding the lake all show evidence of the power of glaciers to carve even the hardest of rock. The mighty glaciers that carved the broad “u-shaped” valley that Lake McDonald sits in also carved smaller hanging valleys with incredible waterfalls accessible by numerous hiking trails.

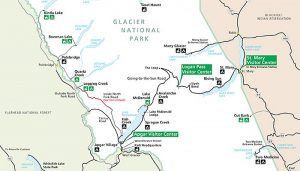

Glacier National Park Map courtesy of the National Park Service.

Along the shore of Lake McDonald sits Lake McDonald Lodge. Originally, this was the site of the Snyder Hotel, which John Lewis bought in 1896. During the winter of 1913-14, Lewis built a new 65-room hotel on the site, constructed to resemble a rustic hunting lodge with Swiss-influenced architecture. Construction materials that could not be locally sourced had to be hauled from the depot in Belton before ferrying nearly ten miles up the lake. The Lewis Hotel became a community gathering point where artist Charlie Russell could sometimes be found telling stories in the lobby. In 1930, Lewis sold the property, and new management changed the hotel’s name to Lake McDonald Lodge. Today, this warm and inviting building provides comfort for overnight guests.

Logan Pass – The highest elevation, at 6646 feet, is reachable by car in the park, Logan Pass is towered over by Reynolds Mountain and Clements Mountains. Beautiful fields of wildflowers can be found in the summer, and plenty of wildlife viewing opportunities, where visitors see mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and the occasional grizzly bear lumbering through the meadows. Also, two of the area’s most popular trails are the Hidden Lake Trail and the Highline Trail. An extremely popular stop with visitors, the parking lot can often be full, so guests are encouraged to use free shuttles or come early or late in the day.

The Logan Pass Visitor Center is located in the middle of the park at the highest point along Going-to-the-Sun Road, approximately 32 miles from the West Entrance and 18 miles from the St. Mary Entrance. It offers ranger-led activities, restrooms, and a shuttle service.

Many Glacier – Situated in the heart of Glacier National Park, massive mountains, active glaciers, sparkling lakes, hiking trails, and abundant wildlife make this a favorite of visitors and locals alike. The small glaciers seen today sculpt the land in much the same way as the larger ancient ice-age glaciers did, slowly grinding away on the mountains, carving rock, and leaving a changed landscape.

Many Glacier is also a destination where one can travel by car, foot, boat, or horseback. But, visitors should know that the access road into the valley is rough, and potholes abound. Low-clearance vehicles should use extra caution, and parking is very limited. In fact, on extremely busy days, access to the valley will be restricted until parking becomes available. Visitors might want to shuttle to the destination. Upon arrival, Many Glacier is a hikers’ paradise with trails radiating in all directions, including two of the most popular hikes in the park, the Grinnell Glacier Trail and the Iceberg Lake Trail. Springtime brings bighorn sheep close to the road, and late summer is the best time to see grizzly and black bears feasting on huckleberries on the slopes above the Swiftcurrent Motor Inn.

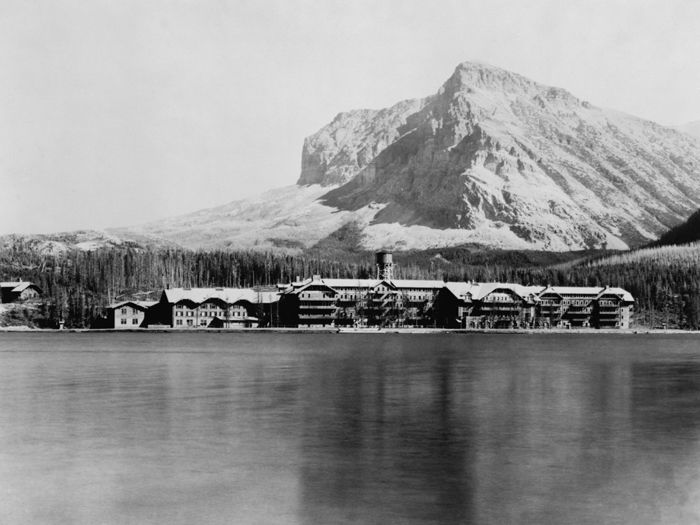

Here sits the historic Many Glacier Hotel, built in 1914-15 by the Great Northern Railway as the showplace of their network of chalets and hotels. A hardy crew of craftsmen overcame the difficulties of building what was then Montana’s largest hotel while withstanding winter temperatures below zero degrees to complete the hotel for a July 4, 1915, opening. Most of the hotel’s timber was logged nearby and milled at a sawmill on the shores of Swiftcurrent Lake. Today’s secluded, five-story hotel contains two suites, seven family rooms, and 205 guest rooms, offering lakeside, deluxe, standard, and value lodging options. Other facilities at the site include a campground, ranger-led activities, hiking, restaurants, a camp store, scenic boat tours and rentals, and horseback riding.

North Fork – This area in the northwest corner of Glacier National Park can only be reached by private vehicles on unpaved roads. Those who travel the rough dirt roads are rewarded with a living laboratory of forest succession in recently burned areas, views of Bowman and Kintla Lakes, homesteading sites, and chances to see and hear rare park wildlife. With limited amenities, the North Fork invites a self-reliant visitor. The only services in this area are available outside of the park in the community of Polebridge, and cell phone signals are nonexistent. Vehicles over 21 feet and/or trailers are prohibited on any North Fork roads. Facilities include four campgrounds, picnic areas, drinking water, and restrooms.

St. Mary Valley – Located adjacent to the St. Mary Entrance Station on Going-to-the-Sun Road, near the town of St. Mary, this is the eastern gateway to Glacier National Park. Here, the prairies, mountains, and forests all converge to create a diverse and rich habitat for plants and animals. A drive along St. Mary Lake, which spans almost ten miles, provides some of the most incredible vistas available in the park. Bordering the Blackfeet Reservation, Native American history and culture are vital in the St. Mary Valley. Blackfeet, Salish, and Kootenai tribal members participate in the park’s Native American Speaks programs. These programs feature award-winning performing artists, local drummers, and dancers at the St. Mary Visitor Center. Facilities and services include two campgrounds, ranger-led activities, hiking, picnic areas, restrooms, and a shuttle service.

Two Medicine – Before Going-to-the-Sun Road was constructed, Two Medicine was a primary destination for travelers arriving by train. After spending a night at Glacier Park Lodge, visitors climbed on horseback to travel to Two Medicine for a night in one of several rustic chalets or canvas tipis built by the Great Northern Railway. From Two Medicine, a system of backcountry tent camps and chalets within the park allowed these adventurous visitors to live in Glacier’s wild interior. Today, Two Medicine has become a somewhat off-the-beaten-path discovery for most park visitors. Backpackers and day hikers find this area rich in scenery, with its incredible vistas, extensive trails, crashing waterfalls, and sparkling lakes. Once discovered, many people consider this their favorite part of Glacier National Park. Facilities and services include a campground, ranger-led activities, hiking opportunities, a camp store, scenic boat tours and rentals, picnic areas, and restrooms.

The historic Glacier Park Lodge is located just outside the boundaries of Glacier National Park in the village of East Glacier Park, Montana. This was the first hotel built by the Great Northern Railway in 1912-13 and has been the first stop on visitors’ Glacier vacations for decades. Today’s visitors can step off the train platform in East Glacier and immediately walk across the street to the lodge grounds. With unpeeled log pillars and open campfire-like fireplaces in the lobby, the lodge acted as a grand entry to the wilderness, as most visitors came by train from the east. The lodge is located at the intersection of U.S. Route 2 and MT-49.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

More Information:

Glacier National Park

PO Box 128

West Glacier, Montana 59936

406-888-7800

Also See:

Glacier National Park Photo Gallery

National Parks, Monuments & Historic Sites

Sources:

Glacier National Park

Glacier’s Past

Man in Glacier

National Park Publications