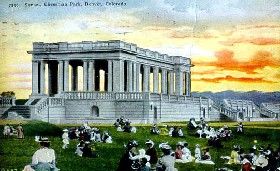

While taking a stroll on the rolling hills or having a picnic under the shade of one of the many trees in the beautiful 80-acre Cheesman Park, many visitors don’t realize that they very well may be walking or sitting right upon the grave of one of the many who were buried here in the 19th century. Surrounded by Capitol Hill mansions in the heart of downtown Denver, Colorado, Cheesman Park is not only frequented by visitors wanting to explore its botanical gardens or enjoy its 150-mile panoramic view from the pavilion but is also said to be home to several restless spirits.

The park’s history began in 1858 when General William Larimer jumped the claim of the St. Charles Town Company and established his town, which he called Denver.

The property didn’t belong to the Town Company either; instead, the land legally belonged to the Arapaho Indians. In November 1858, Larimer set aside 320 acres for a cemetery, now the site of present-day Cheesman and Congress Parks. Larimer called it Mount Prospect Cemetery, and several large plots were designated on the crest of the hill for the exclusive use of the city’s wealthy and most influential citizens. The outermost edge of the cemetery was reserved for criminals and paupers, while the middle class was to be interred somewhere in between.

The first man buried in the cemetery was named Abraham Kay, who died after being suddenly stricken with a lung infection. He was buried on March 20, 1859. However, the most often story told of the first person buried was a man hanged for murder. Making for a far more interesting tale, it has become the preferred version.

The second man buried at the cemetery was a Hungarian immigrant named John Stoefel. Having arrived in Denver to allegedly settle a dispute with his brother-in-law, he shot the man on April 7, 1859. Both men were gold prospectors, and witnesses believed Stoefel was there because he wanted his brother-in-law’s gold dust. Because the nearest official court was in Leavenworth, Kansas, a “people’s court” was assembled, where Stoefel was convicted of murder. On April 9, 1859, he was hanged from a cottonwood tree at the intersection of 10th and Cherry Creek Streets. Though Denver consisted of only 150 buildings then, about 1,000 spectators attended the Stoefel hanging. Afterward, his body and his brother’s were dumped into the same grave at the edge of the cemetery.

As the outermost edge of the cemetery began to fill with outlaws, vagrants, and paupers, Denver citizens began to call the cemetery the “Old Boneyard” and “Boot Hill.” Mt. Prospect gained another nickname when a popular professional gambler named Jack O’Neill was gunned down outside a saloon in March 1860. The event began when O’Neil, a handsome Irish man, quarreled with a less-than-credible man named “Rooker.” O’Neill suggested the two settle the argument with bowie knives in a back room as the argument progressed. However, when Rooker refused, O’Neill questioned his heritage and that of several of his family members. A couple of days later, Rooker shot O’Neil down as he passed by the door of the Western Saloon. When the Rocky Mountain News printed the story, the cemetery also became known as “Jack O’Neil’s Ranch.”

After receiving these many nicknames, the cemetery never gained the respect that Larimer intended for it to have. The influential citizens of Denver’s society were most often buried elsewhere, leaving the graveyard for burials of the poor, criminal, and diseased.

When Larimer eventually left Denver, Mt. Prospect was claimed by a cabinet maker named John Walley, who also just happened to be an aspiring undertaker. A report in 1866 stated that 626 persons were buried in the cemetery. Walley did an extremely bad job of keeping up the cemetery, which soon fell into a terrible state of disrepair as headstones were toppled, graves were vandalized, and sometimes, even cattle were allowed to graze upon the land. Some legends even tell of homesteaders who began to live on the land.

Denver City Cemetery.

In 1872, the U.S. Government determined that the property upon which the cemetery stood was federal land, having been deeded to the government in 1860 by a treaty with the Arapaho Indians. The government then offered the land to the City of Denver and purchased it for $200. The cemetery’s name was changed to the Denver City Cemetery a year later.

Over time, separate areas of the cemetery were designated for various religious, organizational, and ethnic groups, such as the Odd Fellows, Society of Masons, Roman Catholics, Jews, the Grand Army of the Republic, and a far-away segregated section for the Chinese near the pauper’s graves. While family descendants or their organizations well maintained some of these sections, others were neglected.

In 1875, twenty acres at the north part of the cemetery were sold to the Hebrew Burial Society, who then maintained it, while much of the rest of the graveyard grew tall with weeds.

In 1881, a “hospital” for smallpox patients was established just south of the Jewish Cemetery. The hospital, more often referred to as a “pest house,” was where smallpox victims were quarantined. Some had contagious diseases, and some were merely sick, elderly, or handicapped. Most “patients” were left at the pest house to die. Behind the building was the Potter’s Field section of the graveyard, where most of the dead were buried in mass graves.

By the late 1880s, the cemetery was seldom used. It had fallen into even worse disrepair, becoming a terrible eyesore in what had become one of the most prestigious parts of the burgeoning city. Real estate developers soon began to lobby for a park rather than an unused cemetery. Before long, Colorado Senator Teller persuaded the U.S. Congress to allow the old graveyard to be converted into a park. On January 25, 1890, Congress authorized the city to vacate Mt. Prospect, and in recognition, Teller immediately renamed the area Congress Park.

Families were then given 90 days to remove the remains of their departed to other locations. Those who could afford to began to transfer the bodies to other cemeteries throughout the city. Due to many graves in the Roman Catholic section, Mayor Bates sold the 40-acre area to the archdiocese and named the Mount Cavalry Cemetery. The Chinese section of the graveyard was placed in the hands of a large population of Chinese who lived in the “Hop Alley” section of Denver. Most of these bodies were removed and shipped to their homeland, China.

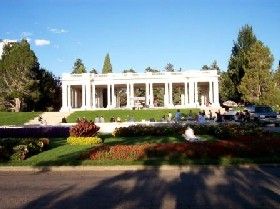

Cheesman Park in Denver, Colorado.

However, most of those buried in the cemetery were vagrants, criminals, and paupers. When most bodies remained unclaimed, the City of Denver awarded a contract to undertaker E.P. McGovern to remove the remains in 1893. McGovern was to provide a “fresh” box for each body and transfer it to the Riverside Cemetery for $1.90 each. The gruesome work began on March 14, 1893, before an audience of curiosity-seekers and reporters. For the first few days, the transfer was orderly. However, the unscrupulous McGovern soon found a way to make a larger profit on the contract. Rather than utilizing full-size coffins for adults, he used child-sized caskets that were just one foot by 3 ½ feet long. Hacking the bodies up, McGovern sometimes used as many as three caskets for just one body. In their haste, body parts and bones were strewn everywhere, and in the disorganized mess, “souvenir” hunters began to loot the open graves and coffins.

When the Denver Republican got hold of the story, its headline proclaimed on March 19, 1893: “The Work of Ghouls!” The article described, in detail, McGovern’s practice of hacking up what were sometimes intact remains of the dead and stuffing them into undersized boxes. The article, in part, described the scene like this:

“The line of desecrated graves at the southern boundary of the cemetery sickened and horrified everybody by the appearance they presented. Around their edges were piled broken coffins, rent and tattered shrouds, and fragments of clothing that had been torn from the dead bodies… All were trampled into the ground by the footsteps of the gravediggers like rejected junk.”

Ghoul.

The Health Commissioner immediately began investigating the matter, so Mayor Rogers terminated the contract. Afterward, the city built a temporary wooden fence around the cemetery, leaving it in shambles with open holes still displayed. Though numerous graves had not yet been reached and others sat exposed, a new contract for moving the bodies was never awarded.

In 1894, grading and leveling began in preparation for the park, though several open graves wouldn’t be filled in until 1902, when many shrubs were planted. The park was finally completed in 1907 without moving the rest of the bodies. Two years later, in 1909, Gladys Cheesman-Evans and her mother, Mrs. Walter S. Cheesman, donated a marble pavilion in memory of Denver pioneer Walter Cheesman. The donation was conditional that part of the park be designated as Cheesman Park, and so it was. The pavilion continues to stand today.

In 1923, the bodies from the Hebrew Burial ground were removed to other sites, and the cemetery returned to the city, where it currently serves as the reservoir in Congress Park.

The section once used as the Chinese cemetery was used as the city tree and shrub nursery until 1930, when a Works Project Administration project converted it into an addition to Congress Park.

In 1950, the Catholic Church moved the remains of those interred in the Mount Cavalry Cemetery and sold the land back to the city. The land is now the location of Denver’s Botanical Gardens.

The vast majority of present-day Cheesman Park was mostly the Protestant portion of the old cemetery. A residential community separates Cheesman from Congress Park.

Today, an estimated 2,000 bodies remain buried in Cheesman Park.

It is no surprise that the spirits of these forgotten, looted, and sometimes desecrated bodies continue to make their presence known, not only at Cheesman Park but in the neighborhood surrounding it.

Almost immediately, when the bodies began to be removed from the cemetery in 1893, strange things began to happen. One of the first reports was when a gravedigger named Jim Astor felt a ghost land upon his shoulders. Astor, who had been looting the graves as he moved the bodies, immediately ran from the graveyard and failed to return to work the next day.

Cheesman Park, Denver, Colorado.

Those living in residences surrounding the graveyard began to report sad and confused-looking spirits knocking at their doors and windows, as well as the sounds of moans coming from the still-yet-open graves.

Today, these restless spirits are still said to occupy the park, and dozens of tales continue to be told of paranormal activities. Most visitors tell of feelings of unexplainable sadness or dread in a place today meant for pleasure and relaxation. However, other reports are more specific, often including hundreds of whispering voices and moans that continue to come from the fields where the open graves once lay.

Children have been seen playing in the park at night before they mysteriously disappear, and a woman is said to have been seen singing to herself before she, too, suddenly vanishes.

On some moonlit nights, the outlines of the old graves can still be seen. Others have also claimed that after lying on the grass, they have found it difficult to get up, as if unseen forces are restraining them.

Yet more reports tell of strange shadows and misty figures wandering through the park in confusion.

Cheesman Park is located at Franklin and 8th Streets and is open from dawn until 11:00 p.m.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Slackjaw of Cheesman Park

By Lee Cook

Ghostly Cheesman Park, Denver, Colorado.

I live and work only blocks from the infamous Cheesman Park in Denver, Colorado. I’ve heard stories of its haunted nature but never thought much of it—until lately.

One night, my friend Rubin and I decided to take a walk through the park. We walked across the south lawn to the pavilion, where several skateboarders were jumping on the sides of the old fountain, and other people were walking about. We talked about work and other mundane things as we strolled away from the old pavilion to the rose gardens, where there is a natural maze of huge rose bushes.

I heard a rattling chain behind us and said, “Rubin, can you hear that?” As I looked around, he replied that he hadn’t heard anything.

“There, I heard it again!” I exclaimed as I heard the chain jingling.

Still, he didn’t hear it, and we could see no one. Continuing our stroll, we moved toward the middle of the big field, which was more open, and sat down in the cool grass to smoke a cigarette.

Moments later, we were surprised to see a kid riding a bicycle with a chain dangling from his pocket. Turning circles around a thin, pale man dressed in what appeared to be a shredded hospital gown covered with blood, the pair moved toward us. To say the least, we were petrified!

As they grew closer, I saw that the pale man’s jaw was broken. He then approached us and asked for a smoke. As I handed him a cigarette, he said, “Did you see them?”

Dumbfounded, I replied, “Who?”

“The ones who did this to me. They stabbed me fifteen times,” the man said.

He then lifted his sleeves to show us what looked like very deep stab wounds in his arms, back, and chest.

Horrified, I said, “Shouldn’t you be in the hospital?”

He shook his head and said, “They let me go because I had no money.”

He then warned us to watch out for “them” and repeatedly stated: “I’m going to get them!”

When I reassured him that we would let him know if we saw “them,” the pair casually moved away from us into the darkness.

When we could no longer see them, Rubin and I ran toward my apartment, never looking back. Afterward, we talked about what we saw for a long time, both confident that we had seen and talked to “the walking dead!”

So, if you ever go out to Cheesman Park at night, know that you just might be questioned by a ghost in a hospital gown who continues to look for his killers. I have dubbed the ghost “Slackjaw.”

Submitted by Lee Cook, November 2005.

Lee worked at King Soopers, a supermarket near Cheesman Park, and lived in an apartment right across the street from the park. He is also a musician and recording artist trying to make a living in this field part-time. Lee is also fascinated with ghosts.

Also See: