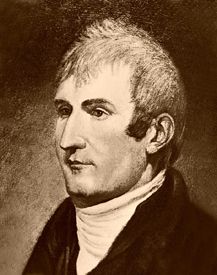

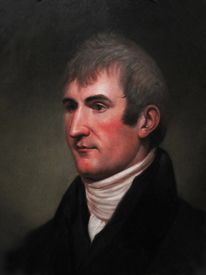

Meriwether Lewis, a diplomat, explorer, scientist, governor, soldier, and the official leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition has been called “undoubtedly the greatest pathfinder this country has ever known.”

Born near Charlottesville, Virginia, to William and Lucy Meriwether Lewis, he faced the world with opportunity and advantage. After William died in 1781, Lucy remarried and moved the family to Georgia when Meriwether was ten. At 13, private tutors sent him back to Virginia for education. He also began to manage his family’s estate. Upon the death of his stepfather, Lewis, not yet out of his teens, became the head of a household that included his mother and four siblings.

Later, he joined the Virginia militia and, in 1794, participated in putting down the Whiskey Rebellion. The following year, he joined the regular army, which he continued to serve until 1801, reaching the rank of captain. During this time, he met and befriended one of his commanding officers, William Clark.

In 1801, shortly after his election, President Thomas Jefferson invited Lewis to serve as his personal secretary, where Lewis became immediately involved in planning the Corps of Discovery Expedition. Lewis served as secretary for less than two years before being reassigned as an intelligent officer who was “fit for the enterprise and willing to… explore… to the Western Ocean.”

Jefferson selected 28-year-Lewis to lead the expedition, afterward known as the Corps of Discovery. Lewis, in turn, selected former Army comrade, 32-year-old William Clark, to be co-leader. Due to bureaucratic delays in the U.S. Army, Clark officially only held the rank of Second Lieutenant at the time. However, Lewis concealed this from the men and shared the expedition’s leadership, always referring to Clark as “Captain.”

In 1803, while preparing for his journey to the Pacific Ocean, Lewis spent a month in Philadelphia studying with the eminent scientists of the day. His education included intensive courses in medicine, preservation of plant and animal samples, using navigation instruments, cartography, and studying fossils.

Between 1804 and 1806, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led the Corps of Discovery from Wood River, Illinois, to the Pacific Ocean. As they traveled, Clark mapped their route, and Lewis recorded information about and collected samples of the unfamiliar plants and animals they encountered. The explorers met with the tribes of the Louisiana Purchase to tell them of the changes that would transpire under U.S. ownership. Lewis and Clark also tried to establish peace between tribes. Not understanding complex intertribal relations and tribal structures, few peace-making efforts met with enduring success.

After three years, the pair returned, and President Thomas Jefferson appointed Lewis governor of the Louisiana Territory in 1806. Taking up his post nearly two years later, Lewis faced challenges almost immediately. Personality conflicts, political differences, and questions about the appropriation of government funds all contributed to his difficulties. Hoping to resolve the financial questions, Lewis set out from St. Louis, Missouri, for Washington D.C., in September 1809. His servant, John Pernia, and Major James Neely traveled with him.

Adding to Lewis’s problems in his career, he was also experiencing personal problems. Meriwether Lewis had long suffered from periodic spells of what was then termed “melancholy.” In addition, land speculation had drained his finances, and he had begun to drink too much. Though his traveling companions worried for his safety and tried to talk him out of taking the trip, Lewis insisted, even though he complained of terrible headaches and a fever.

Just a little more than a month later, Lewis died mysteriously from gunshot wounds on October 11, 1809.

While traveling through Tennessee on October 10, it began to rain heavily, and two of the pack horses fled into the woods. Neelly advised Lewis to continue while he rounded up the horses. Governor Lewis complied and secured lodging at a public roadhouse called Grinder’s Stand. His servant Pernia was given lodging in the barn. Mrs. Grinder would later say that Lewis spent time that evening in the common room pacing and mumbling strangely and that she had heard the gunshots but was too afraid to investigate. The following day, Lewis was found with a gunshot in the head and one in his chest, but he was still alive for a while.

Major James Neelly, Lewis’s traveling companion, arrived at Grinder’s Stand within hours of Lewis’s death and buried his body nearby, where it remains today. He then took charge of Lewis’ papers and carried them the rest of the way to Washington. On October 18, from Nashville, McNeelly wrote to Thomas Jefferson: “It is with extreme pain that I have to inform you of the death of His Excellency Meriwether Lewis, Governor of Upper Louisiana, who died on the morning of the 11th Instant and I am sorry to say by Suicide.”

From the beginning, there were questions about whether Lewis committed suicide or was murdered. Career associates, including Thomas Jefferson, believed that he died at his own hand. However, some family members and others maintained that he was killed. Though most historians today accept that Lewis took his own life, a conspiracy theory also lingers.

Those who believe Meriwether Lewis took his own life have differing theories regarding his reasons, including depression, personal problems, and debilitating illnesses. Major James Neelly, the U.S. agent to the Chickasaw Nation; Captain Gilbert Russell, commander of Fort Pickering in present-day Memphis, Tennessee; and Alexander Wilson, a friend of Lewis’, all reported his death as a suicide in letters and statements written later. Neelly and Russell based their conclusions on personal observations of Lewis’ strange behavior shortly before his death, while Wilson accepted Mrs. Grinder’s story two years after the event. In addition, three men probably closest to Lewis — William Clark and Mahlon Dickerson immediately assumed that Lewis had taken his own life when they heard the news. In a letter to his brother Jonathan, William Clark wrote, “I fear O! I fear the weight of his mind has overcome him.” Thomas Jefferson would later write:

“While he lived with me in Washington, I observed at times sensible depressions of mind… During his western expedition, the constant exertion required of all the faculties of body & mind suspended these distressing affections, but after his establishment in St. Louis in sedentary occupations, they returned upon him with redoubled vigor and began seriously to alarm his friends. He was in a paroxysm of one of these when his affairs rendered it necessary for him to go to Washington.”

Later, some historians theorized that Lewis might have suffered from either paresis, defined medically as “a disorder characterized primarily by impaired mental function, caused by damage to the brain from untreated syphilis.” Others believe he may have been suffering from malaria. Both diseases would affect both his mind and body.

Adding more evidence that Lewis had died by his own hand was that before leaving St. Louis, he had given several associates the power to distribute his possessions in the event of his death, and he had recently composed a will. Reports also surfaced that he had attempted to take his own life several times a few weeks earlier.

Despite what appears to be a clear-cut case of suicide, given Lewis’ state of mind, rumors of murder were circulating as soon as Lewis’ death was made known. Why would such a prominent young man take his own life? And why would he do it in such a way that he would linger in great pain? Several motives were put forth — a jealous husband, robbery, and political assassination.

Because Mr. Robert Grinder was not at home when Lewis was provided lodging, some suspected that when he arrived, he shot Lewis. Some accounts later investigated Robert Grinder due to his coming into a large sum of money. He was also said to have been brought before a grand jury, but the charges were dismissed as no evidence or motive existed for the crime. However, there are no court records.

The robbery motive goes further with numerous suspects, including random bandits known to have lurked upon the wilderness road, Lewis’ servant, John Pernier, and Major James Neelly. As to Major Neelly, Mrs. Grinder would report that Neelly did not react to Lewis’ death. He was conveniently absent all night. Others would say that when he retold the story, it sounded rehearsed. Some documents appeared to be missing when they were delivered to Washington. Neelly was known to be heavily in debt. John Pernia, a Creole, vanished immediately after death, supposedly returning to New Orleans. Later, a watch that belonged to Lewis turned up in New Orleans. The third theory of assassination suggests that Lewis had discovered secrets about General James Wilkinson, his predecessor as Governor of Upper Louisiana. If revealed, it would not only destroy the reputation of General Wilkerson and tarnish that of Thomas Jefferson. For years, Lewis lay in an unmarked grave off the Natchez Trace. However, in 1848, a special commission was established by the State of Tennessee to consider building a monument to Lewis. That commission examined his body, and the physician on the committee wrote in his report that Lewis was most likely a “victim of assassins.”

Today, his isolated burial spot near Hohenwald, Tennessee, is marked by a monument. Even the historical marker at the site acknowledges the controversy surrounding his death, stating that it marks the spot where Lewis’ “life of romantic endeavor and lasting achievement came tragically and mysteriously to its close.”

If his death is not mystery enough, more tales speak of his burial site being haunted. Several visitors have reported having seen ghostly figures, heard voices, and told of restless energy that pervades the spot. Yet others have described specifically hearing the words “so hard to die.” So perhaps what appears to be a suicide is not enough, and Lewis continues to reach out for the mystery to be solved.