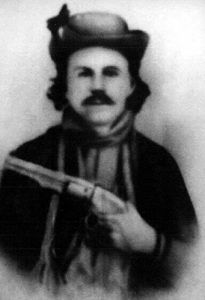

Bob Lee

One of the best-known of all feuds in Texas was the Lee-Peacock Feud. In northeast Texas following the Civil War, this was not simply a feud between families but a continuation of the war that would last for four bloody years after the rest of the nation had laid down their arms.

The feud played out in the Corners region of northeast Texas, where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin Counties converged in an area known as the “Wildcat Thicket.” This thicket, covering many square miles, was so dense with trees, tall grass, briar brush, and thorny vines that few people had even ventured into it until the Civil War when it became a haven for army deserters and outlaws.

It was in the northern part of this thicket that Daniel W. Lee had built his home and raised his son, Bob Lee, who would become one of the leaders in the feud that was to come.

When the Civil War broke out, Bob Lee, though by that time married with three children, quickly joined the Confederate Army, serving with the Ninth Texas Cavalry. Other young men in the area, including the Maddox brothers – John, William, and Francis; their cousin Jim Maddox, and several of the Boren boys, also joined the Ninth.

Towards the end of the war, he began to hear that his home ground had become troublesome, as the Union League, an organization that worked for the protection of the blacks and Union sympathizers, had set up its North Texas headquarters at Pilot Grove, just about seven miles away from the Lee family homes.

At the Union League’s helm was Lewis Peacock, who had arrived in Texas in 1856 and lived just south of Pilot Grove. Though Union sympathizers mainly were persecuted and made outcasts by the predominately Confederate residents during the war, things began to change as Union forces began to put down the Confederates toward the war’s end. By the war’s end, the Union League had grown stronger, and afterward, Federal Troops were sent to Texas to aid in reconstruction efforts.

When the Confederate soldiers returned to their homes in northeast Texas, the area was already rife with conflict. Whether they owned slaves or not, most area residents resented the intrusion of Reconstruction ideals and new laws. When Bob Lee returned home, he was seen as a natural leader for the “Civil War” still being fought in northeast Texas.

To Peacock, however, he saw Lee as a threat to his cause and to reconstruction itself. The Union League conceived the idea of extorting money from Lee to circumvent this. Peacock and his cohorts arrived at Lee’s house one night and “arrested” him, allegedly for crimes he had committed during the Civil War. Lee later said he recognized Lewis Peacock, James Maddox, Bill Smith, Sam Bier, Hardy Dial, Doc Wilson, and Israel Boren. Stating to Lee that he was to be taken into Sherman, they stopped in Choctaw Creek bottoms, where they took Lee’s watch, a $20 gold coin, and forced him to sign a promissory note for $2,000. The Lees refused to pay the note, bringing suit in Bonham, Texas, and winning the case. This started an all-out war known as the Lee-Peacock Feud.

Both men gathered their friends and sympathizers and from 1867 through June 1869, a second “Civil War” raged in northeast Texas, with an estimated 50 men losing their lives. By the summer of 1868, it had become so heated that the Union League requested help from the Federal Government, to which General J.J. Reynolds posted a reward of $1,000 for the capture of Bob Lee.

In late February 1867, Bob Lee was in a store in Pilot Grove when he ran across Jim Maddox, one of the men who had kidnapped him. Confronting Maddox, Lee offered Maddox a gun so they could fight. However, when Lee turned around to walk away, a bullet grazed his ear and head, and he fell to the ground unconscious. Lee was taken to Dr. William H. Pierce, who treated him at home.

A report went to Austin to the Headquarters of the Fifth Military District under the command of General John J. Reynolds, and the following entry was made in his ledger:

“Murder and Assaults with Intent to Kill,” listed as criminals were James Maddox, and John Vaught, listed as injured, was Robert Lee. The charge: “Assault with intent to murder.” The result: “Set aside by the Military.”

A few days later, on February 24, 1867, while Lee was still convalescing in Pierce’s home, Hugh Hudson, a known Peacock man, shot the doctor to death. Lee swore to avenge Pierce’s death, and as word spread to both sides of the conflict, neighbors in the thickets of Four Corners began to arm themselves.

Hugh Hudson, the doctor’s killer, was later shot at Saltillo, a teamster’s stop on the road to Jefferson. The feud had begun in full force. In 1868, Lige Clark, Billy Dixon, Dow Nance, Dan Sanders, Elijah Clark, and John Baldock were killed, and many others were wounded. Even Peacock suffered a wound at the hands of Lee’s followers.

On August 27, 1868, General John J. Reynolds issued the $1,000 reward for Bob Lee, dead or alive, an act that attracted bounty hunters from all over the country to the “Four Corners.” Three of these men, union sympathizers from Kansas, converged on the area in the early spring of 1869 to try to capture Lee. Instead, all three were found dead on the road. Bob Lee, in the meantime, had set up a hideout in the “Wildcat Thicket.”

General J. J. Reynolds responded by dispatching the Fourth United States Cavalry to search for Lee and attempt to settle the trouble in the area. As they began a search from house to house for Lee, in which several gun battles ensued, and several men were killed. In the end, one of Bob Lee’s “supporters,” Henry Boren, betrayed him to the cavalry, who shot down Lee on May 24, 1869. Later, Boren would be shot down by his own nephew, Bill Boren, who was obviously a Lee supporter and felt that a “traitor” had to be put to death. After he killed his uncle, Bill Boren left the area and began to ride with John Wesley Hardin.

As the Texas authorities had hoped, the killing of Lee began to dissolve the two heated factions, as many of them scattered to other parts of the state. However, though their numbers decreased, the “war” would continue for two more years as more men were killed in the four-corners region and other parts of the state. It wouldn’t be until Lewis Peacock was shot on June 13, 1871, that the feud truly ended.

As the Texas authorities had hoped, the killing of Lee began to dissolve the two heated factions, as many of them scattered to other parts of the state. However, though their numbers decreased, the “war” would continue for two more years as more men were killed in the four-corners region and other parts of the state. It wouldn’t be until Lewis Peacock was shot on June 13, 1871, that the feud truly ended.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See: