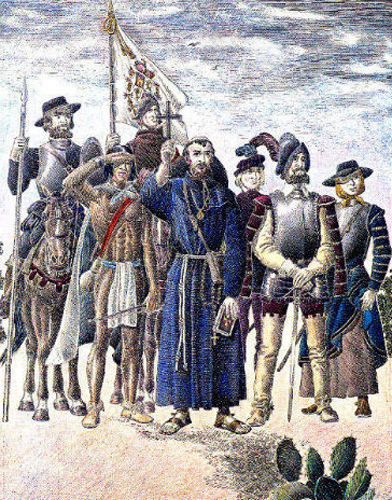

Friar Alonso de Benavides, known as the Custodio y Conversión de San Pablo, the newly appointed ecclesiastical dignitary of the New Mexico mission field, he arrived with a supply caravan in 1626. The Portuguese Franciscan missionary was accompanied by 12 Franciscans, who joined 14 missionaries already residing in New Mexico. Benavides’ arrival signaled a new beginning for the New Mexican missions. The tireless friar toiled in the expanded mission field and promoted it with his prolific quill. Written for the Pope and Spanish king, his Memorial of 1630, and a revised version in 1634 were published in five languages before the end of the 17th century. The New Mexico missions were not unlike other mission provinces in the Americas, an offshoot of the colonial Mexican Church. In his Memorial, Benavides offered a composite, albeit romanticized, view of “the pious tasks of the friars in these conversions.”

Of a day in the life of a missionary, Benavides, seeing through the eyes of a colonial missionary, wrote a description of a friar’s daily routine that could be applied anywhere in the Americas during the Spanish colonial period. Benavides’ Memorial embellished the successes of the New Mexico missions and brushed off the American Indian view — particularly that of anti-mission Pueblo Indians. Their view was often expressed as a rejection of the missionaries. When passive resistance failed, the Indians turned to armed rebellion. The friars ultimately settled for imperfectly converted Christian Indians who integrated Christianity, native beliefs, and spirituality into their customs and traditions despite their goals. The missionaries had satisfied the Spanish government’s objectives to pacify the frontier and the church’s quest to save souls and spread Christianity.

Benavides’ universal description of a day in the life of a missionary resonated in the daily lives of missionaries in remote lands. He wrote:

“Since the land is very remote and isolated and the difficulties of the long journeys require more than a year of travel, the friars, although there are many who wish to dedicate themselves to those conversions, find themselves unable to do so because of their poverty. Hence, only those who go there are sent by the Catholic King, at his own expense, for the cost is too excessive that only his royal zeal can afford it. This is the reason that there are few friars over there and that most of the convents have only one religious each, and he ministers to four, six, or more neighboring pueblos, in the midst of which he stands as a lighted torch to guide them in spiritual as well as temporal affairs. More than 20 Indians, devoted to the service of the church, live with him in a convent. They take turns relieving one another as porters, sextons, cooks, bell ringers, gardeners, refectioners, and other tasks. They perform their duties with as much circumspection and care as if they were friars. At eventide, they say their prayers together, with much devotion, in front of some image.

In every pueblo where a friar resides, he has schools to teach praying, singing, playing musical instruments, and other interesting things. Promptly at dawn, one of the Indian singers, whose turn it is that week, goes to ring the bell for the Prime, at the sound of which those who go to school assemble and sweep the rooms thoroughly. The singers chant the Prime in the choir. The friar must be present at all of this and note those who have failed to perform this duty to reprimand them later. When everything is neat and clean, they again ring the bell, and each one goes to learn his particular specialty; the friar oversees it all so that these students may be mindful of what they are doing. At this time, those who plan to get married come and notify him, so that he may prepare and instruct them according to our holy council; if there are any, either sick or healthy persons, who wish to confess to receiving communion at mass, or who wish anything else, they come to tell him. After they have been occupied in this manner for an hour and a half, the bell is rung for mass. All go into the church, and the friar says mass and administers the sacraments. Mass over, they gather in different groups, examine the lists, and note those absent to reprimand them later. After taking the roll, all kneel by the church door and sing the Salve in their tongue. This concluded, the friar says: “Praised be the Most Holy Sacrament,” and dismisses them, warning them first of the circumstances with which they should go about their daily business.

At mealtime, the poor people in the pueblo who are not ill come to the porter’s lodge, where the cooks of the convent have sufficient food ready, which is served to them by the friars; food for the sick is sent to their homes. After mealtime, it always happens that the friar has to go to some neighboring pueblo to hear a confession or to see if they are careless in the boys’ school, where they learn to pray and assist at mass, for this is the responsibility of the sextons. It is their duty always to have a dozen boys for the service of the sacristy and to teach them how to help at mass and how to pray.

In the evening, they tolled the bell for vespers, which are chanted by the singers who are on duty for the week, and, according to the importance of the feast, they celebrate it with organ chants as they do for mass. Again the friar supervises and looks after everything, the same as in the morning.

On feast days, he says mass in the pueblo very early and administers the sacraments and preaches. Then he goes to say a second mass in another pueblo, whose turn it is, where he observes the same procedure, and then he returns to his convent. These two masses are attended by the people of the tribe, according to their proximity to the pueblo, where they are celebrated.

One of the weekdays, which is not so busy, is devoted to baptism, and all those who are to be baptized come to the church on that day unless some urgent matter should intervene; in that case, it is performed at any time. With great care, their names are inscribed in a book; in another, those who are married; and in another, the dead.

One of the greatest tasks of the friars is to adjust the disputes of the Indians among themselves, for since they look upon him as a father, they come to him with all their troubles, and he has to take pains to harmonize them. If it is a question of land and property, he must go with them and mark their boundaries and thus pacify them.

For the support of all the poor of the pueblo, the friar makes them sow some grain and raise some cattle because if he left it to their discretion, they would not do anything. Therefore, the friar requires them to do so and trains them so well that with the meat, he feeds all the poor and pays the various workmen who come to build the churches. With the wool, he clothes all the poor, and the friar himself also gets his clothing and food from this source. All the wheels of this clock must be kept in good order by the friar without neglecting any detail; otherwise, all would be lost.

The most important thing is the good example set by the friars. This, aside from the obligations of their vows, is forced upon them because they live in a province where they concern themselves with nothing but God. Death stares them in the face every day! Today one of their companions is martyred, tomorrow, another; they hope that such a good fortune may befall them while living a perfect life.”

Though Benavides wrote some of the most detailed documentary information about the Spanish province of New Mexico in the early decades of the 1600s, he only spent three years in the area. When his term was done, he claimed there were 50 well-built and beautifully decorated churches in New Mexico. He also presented a highly rosy picture of relations between the Indians, Franciscans, and lay Spaniards, which was a stretch of the imagination.

However, he did accomplish much during his short tenure, including establishing new missions among the Piro and Tompiro Pueblos. Among the Piro, he founded the Blessed Most Holy Virgin of Socorro church at present-day Socorro, New Mexico. He also oversaw the erection of two other churches and associated conventos, or friars’ residences, among the Piro. He also ordered the construction of a substantial adobe church for the Hispanic residents of Santa Fe. Among the Pueblos of Jemez, he erected one impressive church and rehabilitated another. He also had some success with his missionary work among various bands of Apache.

When a new dignitary arrived to take his place in 1629, Benavides traveled to Mexico City to spread the good news of the province; he was a successful booster of his successes. However, history would later find that he had not relayed or given emphasis to some important information.

During this period, the Spanish colonists had found it necessary to cultivate fear among the Pueblos by often firing their long guns at the native people. However, he admitted: “If this were not the case, the Indians would often be inclined to murder the Spaniards.” Though there was animosity lying just below the surface of early Spanish New Mexico, he mostly ignored and concealed it. He also failed to add that New Mexico’s climate, then as now, was subject to marked extremes of temperature and precipitation, creating problems for Pueblo farmers.

However, Benavides’s descriptions to his superiors in Mexico City were so glowing that he was sent to Spain to persuade the royal court that increased expenditures in New Mexico would be amply rewarded. Thrilled with his stories to his listeners, a written version of his report was published in 1630, and hehe succeeded in obtaining authorization for 30 more friars for New Mexico.

Just three years after his departure, the Zuni Indians rose and killed two friars in 1632. This, however, didn’t affect him, as in 1635, he earned an appointment as auxiliary bishop of the island of Goa, a former Portuguese outpost in the Arabian Sea. He departed for his new post from Lisbon in April 1635, and that was the last time he was ever seen of him. Never reaching his destination, he was presumed drowned at sea.

Compiled by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Missions & Presidios in the United States

San Antonio Missions National Historic Park

Significance of Spanish Missions in America

About the Article: The first portion of this article was written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. and featured by the National Park Service. However, some edits occurred. The source for the latter part of the article, beyond Benavides’ description, is courtesy of the New Mexico Office of the State Historian.