When Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office in 1933, he promptly set about to deliver on his presidential campaign promise of a “New Deal” for everyone. At that time, the nation was in the midst of the Great Depression and in great crisis. It was so bad that some political and business leaders feared revolution and anarchy.

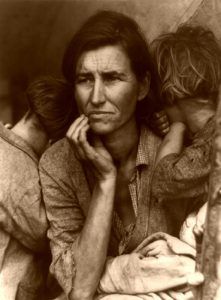

In the previous three years since the stock market crash in October 1929, unemployment in the United States had increased from 4% to 25%, manufacturing output decreased by one-third as prices fell by 20%, and thousands of banks had failed.

In addition to the many who lost their jobs, one-third of those were downgraded to working part-time on much smaller paychecks, resulting in almost 50% of the nation’s human workforce being underutilized. Thousands lost their money in the stock market, and even more lost all financial security when the banks closed. At that time, there were no safety nets – no unemployment insurance, no insurance on bank deposits, and no social security. Each year, conditions worsened, as any relief that might have come from family, private charities, and local governments fell far short in the face of increased demand.

In the summer of 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Governor of New York, was nominated as the presidential candidate of the Democratic Party. In his acceptance speech, Roosevelt addressed the problems of the depression by telling the American people:

Reacting to the ineffectiveness of President Herbert Hoover’s administration in meeting the ravages of the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s campaign promises, Roosevelt won by a landslide in the November 1832 election.

“I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a New Deal for the American people.”

Franklin Roosevelt took the oath of office on March 4, 1933. By then, there were 13,000,000 unemployed, and almost every bank was closed. Of those that remained open, withdrawals were restricted. Farm income had fallen by over 50%, and an estimated 844,000 non-farm mortgages had been foreclosed on.

The day after Roosevelt took office, he began to make changes. That day, he proclaimed a four-day bank holiday and called a special session of Congress to begin March 9.

On the first day of its special session, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act, which gave the president power over the banks. Within a few days, many banks reopened, lifting national spirits.

In his first “hundred days,” he proposed and Congress enacted sweeping programs to alleviate the suffering of the nation’s huge number of unemployed workers, bring recovery to business and agriculture, relief to the unemployed and to those in danger of losing farms and homes, change to the financial system, and other reforms to propel the nation out of its Depression. These included:

- The Reforestation Relief Act established jobs for 250,000 young men in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). By the program’s end in 1941, 2 million people worked on these many projects.

- The Federal Emergency Relief Act provided funds to states for relief.

- The Agricultural Adjustment Act established prices for farm products and paid subsidies to farmers, and the Farm Credit Act provided agricultural loans.

- The Tennessee Valley Authority Act to build dams and power plants.

- The Federal Securities Act gave the executive branch the authority to regulate stocks and bonds.

- The Home Owners Refinancing Act provided aid to homeowners in danger of losing their homes.

- The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) established the Public Works Administration (PWA), which employed people to build roads and public buildings.

- The National Recovery Administration (NRA) to regulate trade and stimulate competition.

- The Banking Act of 1933 created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to protect depositors’ funds.

- The National Labor Board (NLB) protects workers’ rights to join unions to bargain collectively with employers.

In the next few years, more relief and reform legislation was passed, which included:

- The Securities Exchange Act established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to regulate the sale of securities.

- The National Housing Act established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to provide insurance for loans needed to build or repair homes.

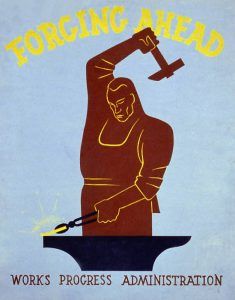

- The Emergency Relief Appropriation Act funded the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to put unemployed workers back to work on public projects. The WPA not only created manual labor jobs in construction and other industries, but it also created jobs for white-collar workers and helped those in the performing and fine arts. The WPA would continue through June 1943, providing jobs for 8.5 million Americans with 30 million dependents.

- The Social Security Administration (SSA) created a basic right to a pension in old age and insurance against unemployment.

- The Farm Security Administration (FSA) to improve the conditions of poor landowning farmers.

Over the years, some of the New Deal laws were declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court because neither the commerce nor the taxing provisions of the Constitution granted the federal government authority to regulate industry or undertake social and economic reform. As a result, in 1937, Roosevelt proposed a reorganization of the court. Though his proposal met with much opposition and ultimate defeat, the court ruled in favor of the remaining contested legislation.

The New Deal program was based on “socialistic” tendencies that the federal government’s power was needed to get the country out of the Depression. Although public support was widespread, not everyone agreed with Roosevelt’s agenda, arguing that the federal government had no place spending millions on public works, going into debt, and regulating business and industry. Others thought that the New Deal did not go far enough and that the federal government should control the banks and industry.

By 1939, the New Deal had run its course. In the short term, New Deal programs helped improve the lives of people suffering from the events of the Depression despite resistance from businesses and politicians. However, in the long run, New Deal programs set a precedent for the federal government to play a key role in the nation’s economic and social affairs. Roosevelt’s domestic programs were largely followed in the Fair Deal of President Harry S. Truman (1945–53), and both major U.S. parties came to accept most New Deal reforms as a permanent part of national life. In the end, these programs produced a political realignment, making the Democratic Party the majority for the next seven out of the nine presidential terms from 1933 to 1969.

Today, historians still debate whether the New Deal succeeded. Those who say it succeeded point out that economic indicators, while they did not return to pre-Depression levels, did bounce back significantly and also point to the infrastructure created by WPA workers as a long-term benefit. Alternatively, critics point out that while unemployment fell after 1933, it remained high. They argue that the New Deal did not provide long-term solutions and only World War II ended the Depression. Furthermore, many critics feel the New Deal changed the government’s role, which did not benefit the nation.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Works Progress Administration of the Great Depression

Federal Writers’ Project – Real Life Stories

The Bum Blockade – Stopping the Invasion of Depression Refugees

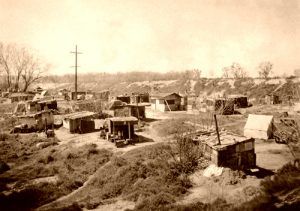

Hoovervilles of the Great Depression

Sources:

American Memory

Encyclopedia Britannica

Library of Congress

Wikipedia