By David Saville Muzzey, 1920

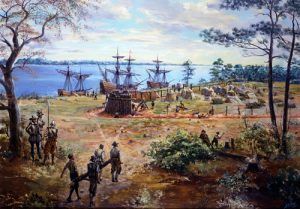

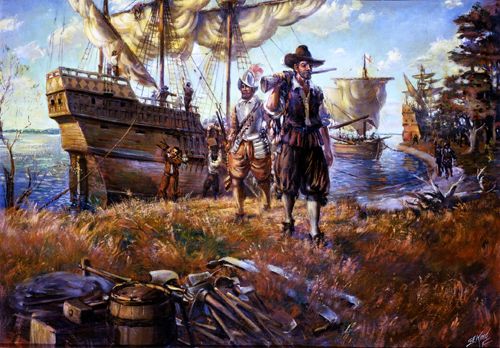

On May 13, 1607, the Jamestown colonists came ashore of what would become the first permanent English settlement in North America. Painting by Sidney E. King, courtesy Colonial National Historical Park

The gorgeous dreams of gold and empire which filled the minds of the explorers of the 16th century slowly faded into the sober realization of the hardships involved in settling the wild and distant regions of the New World. The romantic age of discovery succeeded in the practical age of colonization. The motives which led thousands of Europeans to leave their homes in the 17th century and brave the storms of the Atlantic Ocean to settle on the shores of the James, Charles, Hudson, and St. Lawrence Rivers, were those which have prompted migration in every age; namely, the desire to get a better living and the desire to enjoy a fuller freedom. Now it happened that both these desires were greatly stimulated by the events of the sixteenth century in Europe.

In the first place, the masses of the people, who had lived as serfs on the great feudal estates of the nobles in the Middle Ages, were finding more and more diversified employment as citizens of national states — artisans and mechanics in the towns, free tenant farmers, merchants, and traders.

In other words, a middle class was emerging and was beginning to amass money. At the same time the military and civil expenses of the kings, whose responsibilities were growing with their states, made taxes high and land dear. The limitless virgin lands of the New World offered a tempting relief for the hard-pressed.

In the second place, large parts of northern Europe had broken away from the ecclesiastical authority of the Roman Church in the sixteenth century, in the movement known as the Protestant Reformation. State churches were established in England, Germany, Scandinavia, and the Netherlands, with the rulers in authority instead of the Pope; and dissent from the doctrine of these established churches was treated, not only as religious heresy but also as political treason. But, the spirit of free inquiry and religious innovation which had destroyed the unity of the Roman Church could not be held in check by rulers. Men claimed individual freedom of belief and worship. A great variety of religious sects appeared. Kings and princes tried to reduce them to submission, and the persecutions in Europe sent many refugees as colonists to the New World.

From the 17th to the 20th century the tide of immigration flowed from Europe to America until, by the early 1900s, less than half the population of the United States was native-born with native-born parents. Yet, these immigrants did not transport the political and social institutions of their own lands to the United States, but, instead, with remarkable rapidity, adopted the speech, customs, and ideals of America. For although Spain and France held or claimed by far the largest part of North America, while the English settlements were still confined to a narrow strip along the Atlantic coast, nevertheless those English settlements absorbed all the rest in their spread to the Pacific and made the English civilization — English speech, English political ideals, English common law, English courts and local governments, English codes of manners and standards of culture — the basis of American life. We severed our political connection with England by the American Revolution, but we could not lay aside the culture or destroy the institutions in which our forefathers had been trained for centuries. We still remained the daughter country, though we left the mother’s roof and set up our own establishment.

Queen Elizabeth’s long and glorious reign came to an end in 1603, when she was succeeded on the throne of England by James Stuart of Scotland. In the year 1606, King James gave permission to “certain loving subjects to deduce and conduct two colonies or plantations of settlers to America. The Stuart king began his reign with a pompous announcement of peace with all his European neighbors; consequently, though England claimed all North America by virtue of Cabot’s discovery of 1497, James limited the territory of his grant so as not to encroach on the Spanish settlements of Florida or on the French interests about the St. Lawrence River.

The powers of government bestowed on the new companies were as complicated as the grants of territory. The companies were to have a council of 13 in England, appointed by the king and subject to his control. This English council was to appoint another council of 13 members to reside in each colony, and, under the direction of a president, to manage its local affairs; subject always to the authority of the English council, which in turn, was subject to the king.

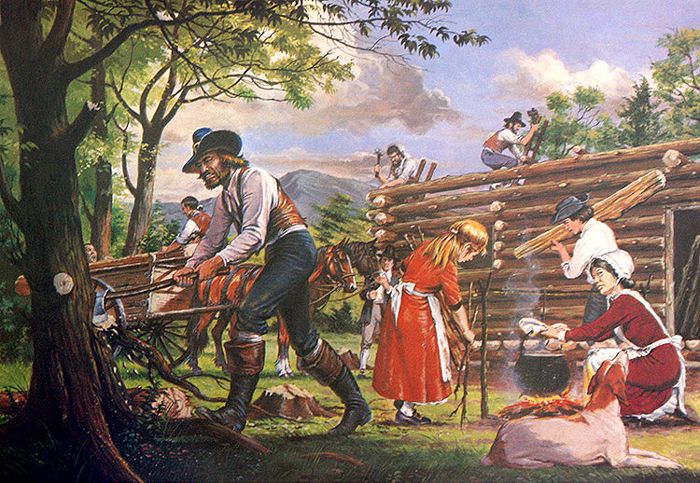

In May 1607, about 100 colonists, sent out by the London Company, reached the shores of Virginia and sailing at some miles up a broad river started a settlement on a low peninsula. They named the river and settlement James and Jamestown in honor of the king. However, the colony did not thrive.

The charter provided that the harvests should be gathered into a common storehouse, and then dispensed to the settlers, thus encouraging the idle and shiftless to live at the expense of the industrious. Authority was hard to enforce with the clumsy form of government, and the proprietors in England were too far away to consult the needs of the colonists. Exploring the land for gold and the rivers for a passage to Cathay proved more attractive to the settlers than planting corn. In addition, the unwholesome site of the town caused fever and malaria.

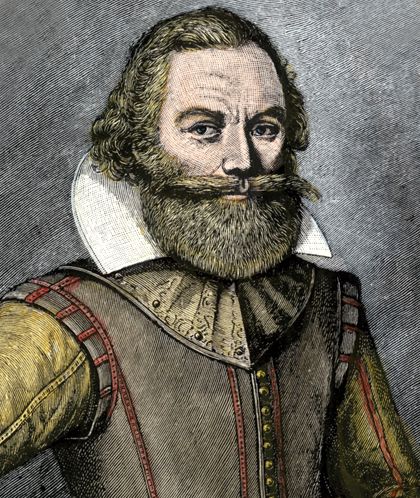

Had it not been for the almost superhuman efforts of one man, Captain John Smith, the little colony could not have survived. Smith had come to Virginia after a romantic and worldwide career as a soldier of fortune. His masterful spirit, at once, assumed the direction of the colony in spite of its president and council. His courage and tact with the Indians got corn for the starving settlers, and his indomitable energy inspired the good and cowed the lazy and the unjust. In his vivid narratives of early Virginia in 1624, he gave himself and his services to the colony full credit, for he was not a modest or retiring man. But his self-praise does not lessen the value of his services. In the summer of 1609, he was wounded by an explosion of gunpowder and returned to England.

The winter following Captain John Smith’s departure was the awful “starving time.” Of five hundred men in the colony in October, only 60 were left in June. This feeble remnant, taking advantage of the arrival of ships from the Bermudas, determined to abandon the settlement. With but a fortnight’s provisions, which they hoped would carry them to Newfoundland, they bid a final farewell to the scene of their suffering and dropped slowly down the broad James River. But, on reaching the mouth of the river they spied ships flying England’s colors. It was the fleet of Lord de la Warre (Delaware), the new governor, bringing men and supplies. Thus, narrowly did the Jamestown colony escape the fate of Raleigh’s settlements. De la Warre brought more than food and recruits. The London Company had been reorganized in 1609, and a new charter granted by the king, which altered both the territory and the government of Virginia.

Henceforth, a large and rich corporation in England was to conduct the affairs of the company, without the intervention of the king. Virginia was to have a governor sent out by the company. Under the new regime, the colony picked up, Order was enforced under the harsh but salutary rule of Governor Dale. The colonists, losing the gold fever, turned to agriculture and manufacturing.

Tobacco became the staple product of the colony, and experiments were made in producing soap, glass, silk, and wine. A better class of emigrants came over, and in 1619 a shipload of “respectable maidens” arrived, who were auctioned off to the bachelor planters for so many pounds of tobacco apiece. At the same time, the sharing of harvests in common was abandoned, and the settlers were given their lands in full ownership.

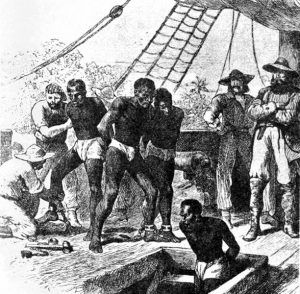

The year 1619, which brought the Virginian’s wives and lands, is memorable also for two events of great significance for slavery and later history of the colonies and the nation. In that year the government’s first cargo of black slaves was brought to the colony, and the ‘first representative assembly convened on American soil. On July 30th, two citizens from each plantation met with the governor and his six councilors in the little church at Jamestown. This tiny legislature of 27 members, after enacting various laws for the colony, adjourned on August 4th. Spanish, French, and Dutch settlements existed in America at the time of this first Virginia assembly, but none of them had or copied later the system of representative government. Democracy was England’s gift to the New World.

The man to whom Virginia owed this great boon of self-government, and whose name should be known and honored by every American, was Sir Edwin Sandys, treasurer of the London Company. Sandys belonged to the country party in Parliament, who was making James’ life miserable by their resistance to his arbitrary government based on “divine right,” or responsibility to God alone for his royal acts. In the meantime, Gondomar, the Spanish minister in London, whispered in James’s ear that assemblies like that in Virginia were “hotbeds of sedition.”

But, James had let the London Company get out of his hands by the new charter, and when he tried to interfere in their election of a treasurer, they rebuked him by choosing one of the most prominent of the country party, the Earl of Southampton. Not being able to dictate to the company, James resolved to destroy it. In a moment of great depression for the colony, just after a horrible Indian massacre in 1622 and a famine, James commenced suit against the company, which a subservient court declared had overstepped its legal rights and forfeited its charter. James then took the colony into his own hands and sent over men to govern it that was responsible only to his Privy Council. Virginia thus became a “royal province” in 1624, and remained so for one hundred fifty years, until the American Revolution.

James intended to suppress the “seminary of sedition” too and rule the colony by a committee province of his courtiers. But he died before he had a chance to extinguish the liberties of Virginia, and his son, Charles I, hoping to get the monopoly of the tobacco trade in return for the favor, allowed the House of Burgesses to continue. So, Virginia furnished the pattern which sooner or later nearly all the American colonies reproduced, namely, that of a governor with a small council appointed by the English king, and a legislature, or assembly, elected by the people of the colony.

The people of Virginia were very loyal to the Stuarts. When the quarrel between King and Parliament in England reached the stage of the civil war in 1642, and Charles I was driven from his throne and beheaded in 1649, many of his supporters in England immigrated to Virginia, giving the colony a decidedly aristocratic character. And, when Charles II was restored to his father’s throne in 1660, the Virginian citizens recognized his authority so promptly and enthusiastically that he called them “the best of his distant children.”

He even elevated Virginia to the proud position of a “dominion,” by quartering its arms (the old seal of the Virginia Company) on his royal shield with the arms of England, Scotland, and Ireland. The Virginians were very proud of this distinction, and remembering that they were the oldest as well as the most faithful of the Stuart settlements in America, adopted the name of “The Old Dominion.”

Though there were actually many occasions of dispute between the governors sent over by the king and the legislature elected by the people, only one incident of prime importance occurred to disturb the peaceful history of the Old Dominion under its royal masters. In 1675 the Susquehannock Indians were harassing the upper settlements of the colony, and Governor William Berkeley, who was profiting largely by his private interest in the fur trade, refused to send a force of militia to punish them. He was supported by an “old and rotten” House of Burgesses, which he had kept in office, doing his bidding, for 14 years.

A young and popular planter named Nathaniel Bacon, who had seen one of his overseers murdered by the Indians, put himself at the head of 300 volunteers and demanded an officer’s commission of Governor Berkeley. Berkeley refused, and Bacon marched against the Indians without any commission, utterly routing them and saving the colony from tomahawk and firebrand.

The governor proclaimed Bacon a rebel and set a price upon his head. In the distressing civil war which followed, the governor was driven from his capital and Jamestown was burned by the “rebels.” But, Bacon died of dysentery shortly after his victory, and his party, being made up only of his personal following, fell to pieces. Berkeley returned and took grim vengeance on Bacon’s supporters until the citizens petitioned him to “spill no more blood.”

Bacon’s Rebellion, despite its deplorable features, did good work. It showed that the colonists dared to act for themselves. It forced the dissolution of the “old and rotten” assembly and the choice of a new one representing the will of the people. It led to the recall of Governor Berkeley by King Charles II, who explained indignantly when he heard of the governor’s cruel reprisals: “That old fool has taken away more lives in that naked country than I did here for the murder of my father.” And, finally, it showed that the people of the Old Dominion, though loyal to their king, had no intention of submitting to an arbitrary governor in collusion with a corrupt assembly.

Today, historic Jamestown is part of the Colonial National Historic Park. The park provides views of both Old Towne, where a triangular fort was constructed by English settlers in the spring of 1607, as well as New Towne, east of the fort, which was first surveyed in the 1620s. Jamestown served as the capital of Virginia until 1699, when it was moved to Williamsburg.

Jointly administered by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities and the National Park Service, the site is located at 1368 Colonial Parkway, Jamestown, Virginia.

Replicas of the three ships which carried settlers to the Virginia settlement in 1607 are docked in the harbor. Photo courtesy National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

By David Saville Muzzey, 1920. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated May 2021.

Also See:

Jamestown – First Successful English Settlement

Nathaniel Bacon — First American Rebel