Mission San Juan Capistrano is a Spanish mission in San Juan Capistrano, California. The birthplace of Orange County, it was founded over 240 years ago by Spanish colonists as the seventh of 21 Catholic missions in California. Today, it is a monument to California’s multicultural history, embracing its Native American, Spanish, Mexican, and European heritage.

The Spanish established these missions from 1769 through 1823 to provide control over the area and its indigenous peoples. Once established, each Mission developed its economy through cattle ranching and farming.

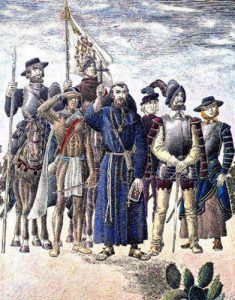

Father Junipero Serra of the Franciscan Order permanently founded Mission San Juan Capistrano on November 1, 1776. It was named for Saint John of Capistrano, a 14th-century theologian and “warrior priest.” The Spanish Colonial Baroque-style church was in the Alta California province of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. It was initially started on October 30, 1775, by Father Fermin Lasuen, but it had to be abandoned after only a week when Kumeyaay Indian warriors destroyed Mission San Diego at the beginning of November. The soldiers and missionaries were ordered back to San Diego to reinforce the garrison.

Mission San Juan Capistrano was established to expand Spain’s territorial boundaries and spread Christianity to the native peoples. Missions and presidios were projected to be the major institutions to spread Spanish rule. They were also to be agents of assimilation, convincing the native people to become Catholics and teaching them the fundamentals of Spanish agricultural and village life to become self-sustainable. Presidios were built to protect the missions from hostile natives and the territory from potential incursion by other foreign powers.

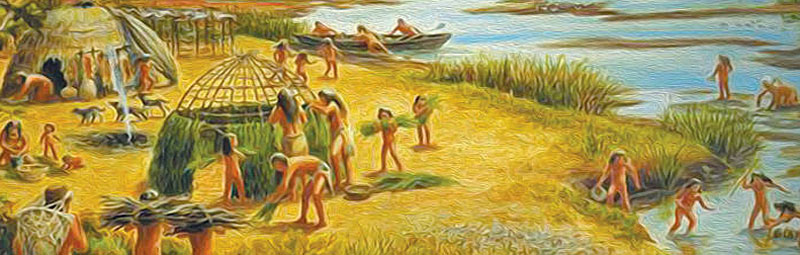

The mission’s establishment as a center for agriculture, industry, education, and religion meant many changes and challenges for the indigenous Acjachemen people of the area. Introducing new technology, clothing, food, animals, and ideas, the missionaries encouraged the Acjachemen to learn about the Catholic faith and be baptized to join the Mission. However, officially joining the Mission meant the Acjachemen had to change almost everything about their life, including their culture, language, religion, work, clothing, food, and daily schedule.

The adobe chapel of Mission San Juan Capistrano, built with the help of local Indians, was dedicated in 1778 by Father Junipero Serra. These natives were later named Juaneno Indians. The Serra Chapel, the only original Mission Church where Father Serra was known to have celebrated sacraments in California, still stands today.

The Criolla, or “Mission grape,” was first planted at San Juan Capistrano in 1779, and in 1783 the first wine produced in Alta California was from the Mission’s winery.

In 1794, The Great Stone Church construction began in the shape of a cross. The church is 180 feet long by 40 feet wide, with a 120-foot bell tower. The sandstone building sat on a foundation seven feet thick. Construction efforts required the participation of the entire neophyte population. Stones were quarried from gullies and creek beds up to six miles away and transported in carts drawn by oxen, carried by hand, and even dragged to the building site. Limestone was crushed into a powder on the Mission grounds to create a more erosion-resistant mortar. On the afternoon of November 22, 1800, tremors from the 6.5-magnitude San Diego earthquake cracked the walls of the Great Stone Church, necessitating repair work.

The church was finally completed in 1806 and blessed by Fray Estévan Tapís on September 7, followed by a two-day-long fiesta. The sanctuary floors were paved with diamond-shaped tiles, and brick-lined niches displayed the statues of various saints. Local legend said the tower could be seen for ten miles or more, and the bells could be heard from farther away. The mission complex included the chapel, the Great Stone Church, workshops, granaries, residences, kitchens, and a hospital.

Unfortunately, on the morning of December 8, 1812, a series of large earthquakes shook Southern California during the Sunday service. The 7.5-magnitude earthquake racked the doors to the church, pinning them shut. When the ground finally stopped shaking, the bulk of the nave had come crashing down, and the bell tower was obliterated. The earthquake destroyed the Church, and 42 people died. The priests immediately resumed holding services in Serra’s Church.

As the transept, sanctuary, and sacristy were left standing, an attempt was made to rebuild the stone church in 1815. However, it failed due to a lack of construction expertise. Afterward, the Mission began to decline.

On December 14, 1818, the French privateer Hipólito Bouchard, sailing under an Argentina flag, brought his ships La Argentina and Santa Rosa to within sight of the Mission. Aware that Bouchard had recently conducted raids on the mission settlements at Monterey and Santa Barbara, Comandante Ruíz sent forth a party of 30 men under Spanish Lieutenant Santiago Argüello to protect Mission San Juan Capistrano at the first news of the approach on December 13. When two members of Bouchard’s contingent made contact with the garrison soldiers, they demanded provisions; they were rebuffed.

Lieutenant Argüello replied that if the ships did not sail away, the garrison would gladly provide “an immediate supply of shot and shell.” In response, Pirate Bouchard ordered an assault on the Mission, sending some 140 men and two or three light howitzer cannons to take the supplies by force. Though the Mission guards engaged the attackers, they were quickly overwhelmed; and the pirates looted the Mission warehouses, left minor damage to several buildings, and set fire to a few outlying straw houses. Reinforcements from Santa Barbara and Los Angeles, led by Comandante Guerra from El Presidio Real de Santa Bárbara, arrived the next day, but it was too late — the ships had already set sail.

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, making Alta California a Mexican territory. Under new governmental direction, the Mission faced continued decline. Disease thinned out the once ample cattle herds, and a sudden infestation of mustard weed made it increasingly difficult to cultivate crops. Floods and droughts took their toll as well. Over time the disillusioned Indian population gradually left the Mission, and without regular maintenance, its physical deterioration continued at an accelerated rate.

On July 25, 1826, José María de Echeandía, the first native Mexican to be elected Governor of Alta California, issued his “Proclamation of Emancipation.” At that time, all Indians within the military districts of San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Monterey who were found qualified were freed from missionary rule and made eligible to become Mexican citizens.

Even though Echeandía’s emancipation plan was met with little encouragement from the neophytes who populated the southern missions, he was determined. He appointed a board of commissioners to oversee the emancipation of the Indians. Because some Spanish missionaries refused to take the oath of allegiance to the “bogus republic of Mexico,” the Mexican government passed legislation on December 20, 1827, that mandated the expulsion of all Spaniards younger than 60 years of age from Mexican territories. After that, the Franciscans abandoned the Mission, taking almost anything of value with them. The locals then plundered many of the Mission buildings for construction materials.

The Mexican government secularized the Mission in 1833. By the next year, the population of San Juan Capistrano had decreased to 861 people. By 1835, little of the Mission’s assets remained. By 1840 it was probably less than 500, with less than 100 at the pueblo proper. The Mission was declared “in a ruinous state,” and the Indian pueblo was dissolved in 1841. The first secular priest to take charge of the mission, Reverend José Maria Rosáles, arrived on October 8, 1843. Vicente Pascual Oliva, the last resident missionary, died on January 2, 1848.

Governor Pio Pico sold the property to his brother-in-law Juan Forster and James McKinley in exchange for hides and tallow in 1845. The Forster family resided at the Mission until 1864.

After the Mexican-American War of 1848, California became a state in 1850. California’s Catholic bishop, Joseph Alemany, petitioned the U.S. government to return mission buildings and lands to the Catholic Church.

A smallpox epidemic swept through the area in 1862, nearly wiping out the remaining Juaneño Indians.

In 1865, United States President Abraham Lincoln returned Mission lands to the Roman Catholic Church.

Starting in the 1870s and throughout the early 1900s, artists, photographers, and visionaries were interested in the missions.

By 1891 a roof collapse required that the Serra Chapel be abandoned entirely. Modifications were made to the original adobe church to render it suitable for use as a parish church.

Numerous efforts were made over the latter 19th century to restore the Mission to its former state, but none succeeded until Father St. John O’Sullivan arrived in 1910. The padre was one of San Juan Capistrano’s greatest preservation proponents, ushering in a new era for the landmark.

Severe flooding destroyed a portion of the Mission’s front arcade in 1915, and heavy storms a year later washed away one end of the barracks building. The Mission grounds were enclosed with a wood picket fence, and beginning on May 9, 1916, a ten-cent admission fee was charged to help defray preservation costs. In 1917, Father St. John O’Sullivan rebuilt the barracks building. In 1918, the Mission was given parochial status, with O’Sullivan serving as its first modern pastor.

In 1925 the full restoration of the Serra Chapel was completed. O’Sullivan died in 1933 and was interred in the Mission cemetery. Afterward, Arthur J. Hutchinson assumed leadership of the Mission and played a central role in raising needed funds to continue the Mission’s preservation work.

In 1937, U.S. National Park Service’s Historic American Buildings Survey representatives extensively visited and photographed the grounds and structures. Their efforts laid the groundwork for future excavation and reconstruction of the west wing industrial complex.

In 1984, a modern church complex was constructed northwest of the Mission compound, now known as Mission Basilica San Juan Capistrano. Today, the mission compound serves as a museum, with the Serra Chapel within the compound serving as a chapel for the mission parish.

Today the mission hosts over 500,000 visitors annually.

Partial reinforced ruins of The Great Stone Church are still visible today. The 1788 Serra Chapel, located just northwest of The Great Stone Church, has the original baroque, hand-carved alter with gold leaf overlay from Barcelona, Spain, and was renovated in 2008. The church is still used for daily services.

The existing rectangular adobe buildings on the site are well preserved, and portions of the gardens retain significant representations of the working mission and interpretive sites commemorating the Juaneno Indians who inhabited the area.

The 1791 soldier’s barracks provides interpretive scenes of life while stationed at the Mission. A water ditch, used to connect the Mission to the nearby river for everyday Mission use, has been preserved near the Soldier’s Barracks. The Padres’ living quarters, kitchen, storerooms, and warehouse have also been restored.

Several large, square courtyards with central water fountains are elaborately decorated with trees, plants, grasses, and various landscape elements, which help create a romantic atmosphere of past Mission life.

While the ruins of “The Great Stone Church” are a renowned architectural wonder, the Mission is also well known for the annual “Return of the Swallows.” Every year on March 19, St. Joseph’s Day, the swallows fly 6,000 miles from Goya, Argentina, to San Juan Capistrano.

More Information

Historic Mission San Juan Capistrano

26801 Ortega Highway

San Juan Capistrano, CA 92675

949-234-1300

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2023.

Also See:

Acjachemen People of Southern California

Spanish Missions in California

Spanish Missions & Presidios Photo Gallery

Sources:

Historic American Landscapes Survey

National Park Service

Mission San Juan Capistrano

Wikipedia