Southern California Indians

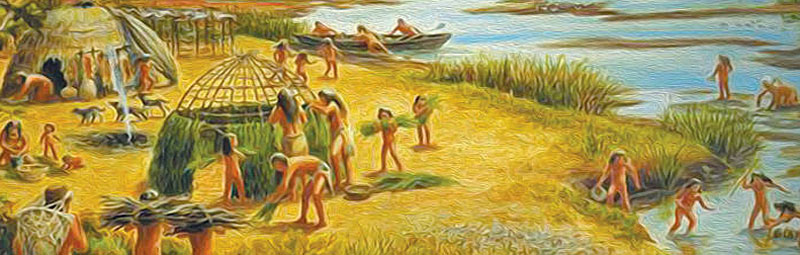

The Acjachemem (Ah-HAWSH-eh-men) people historically lived in present-day Orange, northern San Diego, southern Los Angeles, and western Riverside Counties of California. Archaeological evidence shows they lived there for over 10,000 years. They are very closely related to the Quechnajuichom or Luiseño people to the south, both culturally and linguistically.

Living in permanent, well-defined villages and seasonal camps, village populations ranged between 35 and 300 inhabitants. The village size depended upon if it was a single lineage or a dominant clan joined with other families. While the placement of residential huts in a village was not regulated, the ceremonial enclosure and the chief’s home were most often centrally located.

Each clan had its own territory and was “politically” independent. They believed in owning private property, including land and goods. Though villages were autonomous, ties to other villages were maintained through the immediate region’s economic, religious, and social networks.

There was a well-developed political system, including a hereditary chief. Native leadership consisted of the Nota, or clan chief, who conducted community rites and regulated ceremonial life with the council of elders. The people were composed of three hierarchical social classes — the elite class comprised chiefly of families, lineage heads, and other ceremonial specialists; a middle class of established and successful families; and a lower class of disconnected or wandering families and war captives.

The Acjachemen had a patrilineal society and lived in groups with other relatives. These groups had established claims to places, including their villages’ sites and resource areas. Marriages were usually arranged from outside villages establishing a social network of related peoples in the region.

Religion was an important aspect of their society, which included ceremonies of puberty rites of passage and mourning rituals.

In addition to hunting terrestrial animals, they harvested seafood, including marine mammals.

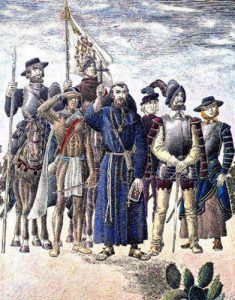

Although earlier explorers had contact with the Acjachemem, they began to be associated with the Spanish when colonists arrived in the early 1770s. At that time, the highest concentration of Acjachemen villages was along the lower San Juan Creek. In 1775, the Spanish erected a cross on an Acjachemen religious site before retreating to San Diego due to a revolt at Mission San Diego. The next year, Father Junipero Serra, Spanish soldiers, and a recently baptized “neophyte” Indian returned to the area. The native was a translator for the Spanish authorities when a crowd of painted and well-armed Acjachemen men surrounded the intruders. The “neophyte” informed the Acjachemen that attacking would only result in further violence from the Spanish military. As a result, the warriors desisted, aware of the serious threat that military retaliation represented.

On November 1, 1776, Father Junipero Serra founded Mission San Juan Capistrano as the seventh of 21 missions to be established in California by the Spanish. Immediately, the missionaries began to convert the Acjachemen people. Early converts were often children whose parents may have brought in an attempt to make alliances with missionaries, who had new knowledge and goods and presented the “threat of force.” Those who had been converted, both children and adults, were known as “Juaneños.” Until 1783, they represented a relatively small percentage of the Acjachemen population.

During the late 18th century, the mission economy extended over the entire territory of the Acjachemen, and things began to change for the tribe. The mission system and colonization effectively destroyed the collectively owned areas and private property system of the Acjachemen as the Spanish transformed the countryside into grazing lands for livestock and horticulture. Between 1790 and 1804, the mission herds increased from 8,034 to 26,814 head. The Spanish military presence ensured the mission system’s continuation in the next years, and most non-converts were baptized. By 1812, the mission was at the peak of its growth, at which time, 3,340 people had been baptized, and 1,361 Juaneños resided in the mission compound. Afterward, the number of Juaneños who died surpassed those who were baptized, as European disease began to decimate the native population as the power of the Spanish missions further increased.

However, the Acjachemen resisted assimilation by practicing their cultural and religious ceremonies and performing sacred dances and healing rituals in villages and within the mission compound. Missionaries attempted to prevent these customs from passing on to younger generations by placing recently baptized Indian children in monjerios (chaperoned dormitories), away from their parents, from about seven years old until their marriage.

Additionally, children and adults were punished for disobeying Spanish priests through confinement and lashings. Gerónimo Boscana, a missionary at San Juan between 1812 and 1822, admitted that, despite harsh treatment, attempts to convert Native people to Christian beliefs and traditions were largely unsuccessful, stating, “the true believer was the rare exception.”

On July 25, 1826, the first Mexican governor of Alta California, José María de Echeandía, issued a “Proclamation of Emancipation,” which freed Native people from San Diego Mission, Santa Barbara, and Monterey. When news of this spread to other missions, it inspired widespread resistance to work and sometimes open revolt. At San Juan Capistrano, the missionary stated that if the 956 neophytes residing at the mission in 1827 were ‘kindly begged to go to work,’ they would respond by saying simply that they were ‘free.'”

Following the Mexican Secularization Act of 1833, the neophyte alcades requested that the community be granted the land surrounding the mission, which the Juaneños had irrigated and were using to support themselves.

By 1834, the Juaneño population had declined to about 800.

While rancho grants issued by the Mexican government on the lands of the San Juan Mission were made in the early 1840s, the land was “never formally ceded” with a legal title, and their village lands went unrecognized. Though “free,” they were increasingly vulnerable to being forced to work on public projects. Because of a lack of formal recognition, most of the former Acagchemem territory was incorporated into Californio ranchos by 1841 when San Juan Mission was formed into a pueblo. However, the formation of the San Juan pueblo granted both Californios and Juaneño families lots for houses or plots of land to plant crops.

Following the American occupation of California in 1846 and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the native population continued to decline while any rights under Mexican rule were completely erased. During this time, the claims of Indians who had acquired land in the 1841 formation of the San Juan pueblo were ignored, despite evidence that the American land commission had data substantiating these Juaneños’ titles.

By 1860, Juaneños were recorded in the census with Spanish first names and no surnames, the occupations of 38% of their heads of household went unrecorded, and they owned only one percent of the land. After the census, almost all the natives began to leave the area for villages to the southeast of San Juan. In 1862, a smallpox epidemic took the lives of 129 Juaneño people in a single month, leaving only 227 Juaneños remaining. The remaining natives then established themselves among the Luiseño, with who they shared linguistic and cultural similarities, family ties, and colonial histories.

In the 1990s, the Acjachemen Nation was divided into three different governments, all claiming their identity as the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation. Today, the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation, is recognized as a tribe by the state of California.

Though they filed a petition in 1982 to seek federal recognition as a tribe and are working with the Bureau of Indian Affairs on documentation, they are still not federally recognized today.

The Juaneño Band of Mission Indians has organized a government. It elects a tribal council assisted by tribal elders. The Juaneño Band headquarters is in San Juan Capistrano. There are more than 2,800 enrolled members.

Though their language became extinct by the early 20th century, the tribe is working at reviving it, with several members learning it.

More Information:

Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation

31411 La Matanza St Suite A

San Juan Capistrano, California 92675

949-488-3484

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2023.