The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes from about 1760 to about 1830. During this time, the production of goods moved from home businesses, where products were generally crafted by hand, to machine-aided production in factories. This revolution, which involved significant changes in transportation, manufacturing, and communications, transformed the daily lives of Americans as much as — and arguably more than — any single event in U.S. history.

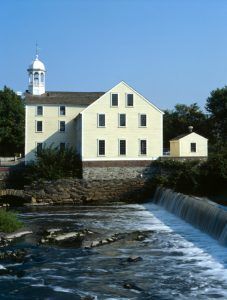

An early landmark moment in the Industrial Revolution came near the end of the 18th century when Samuel Slater brought new manufacturing technologies from Britain to the United States and founded the first U.S. water-powered cotton mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Like many of the mills and factories that sprang up in the next few decades, Slater’s Mill was powered by water, which confined industrial development to the Northeast at first. The concentration of industry in the Northeast also facilitated the development of transportation systems such as railroads and canals, which encouraged commerce and trade.

A major supporter of the industrial revolution was Alexander Hamilton. After the American Revolution ended, he began promoting his views on the economic needs of the new nation. He was concerned over the lack of industry in the United States; it was prohibited by English law during colonial times. Hamilton believed that a strong industrial system was the best way to help the United States gain financial independence and become a world presence.

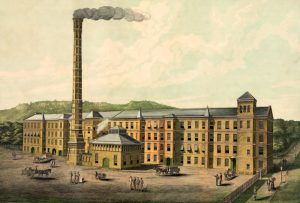

After Hamilton was appointed as the United States’ first Secretary of the Treasury, he continued to advocate for the establishment of industry in America. Toward that end, he co-founded the “Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures,” which would be operated by private interests but would have the support of the government. The organization’s charter called for the society to both manufacture goods and trade in them. In 1792, the group purchased 700 acres of land above and below the Great Falls and established the city of Paterson, New Jersey. It was America’s first planned industrial city, and here, the methods for harnessing water power for industrial use were pioneered. Many of the factories that were established enabled the young United States to become an economic player on the world stage.

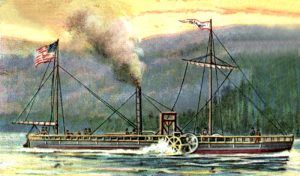

The technological innovation that would come to mark the United States in the 19th century began to show itself with Robert Fulton’s establishment of steamboat service on the Hudson River, Samuel F. B. Morse’s invention of the telegraph, and Elias Howe’s invention of the sewing machine, all before the Civil War.

Following the war, industrialization in the United States increased at a breakneck pace. This period, encompassing most of the second half of the 19th century, has been called the Second Industrial Revolution or the American Industrial Revolution. Over the first half of the century, the country expanded greatly, and the new territory was rich in natural resources. Completing the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 was a major milestone, making transporting people, raw materials, and products easier. The United States also had vast human resources: between 1860 and 1900, 14 million immigrants came to the country, providing workers for various industries.

Andrew Carnegie’s U.S. Steel Works, Duquesne, Pennsylvania by the Historic American Buildings Survey

The American industrialists overseeing this expansion were ready to take risks to make their businesses successful. Andrew Carnegie established the first steel mills in the U.S. to use the British “Bessemer process” for mass-producing steel, becoming a titan of the steel industry in the process. He acquired business interests in the mines that produced the raw material for steel, the mills and ovens that created the final product, and the railroads and shipping lines that transported the goods, thus controlling every aspect of the steelmaking process.

Other industrialists, including John D. Rockefeller, merged the operations of many large companies to form a trust. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust came to monopolize 90% of the industry, severely limiting competition. These monopolies were often accused of intimidating smaller businesses and competitors to maintain high prices and profits. Economic influence gave these industrial magnates significant political clout as well. The U.S. government adopted policies that supported industrial development, such as providing land for the construction of railroads and maintaining high tariffs to protect American industry from foreign competition.

American inventors like Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Alva Edison created a long list of new technologies that improved communication, transportation, and industrial production. Edison made improvements to existing technologies, including the telegraph, while also creating revolutionary new technologies such as the light bulb, the phonograph, the kinetograph, and the electric dynamo. Bell, meanwhile, explored new speaking and hearing technologies and became known as the inventor of the telephone.

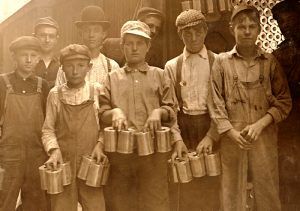

For millions of working Americans, the industrial revolution changed the very nature of their daily work. Previously, they might have worked for themselves at home, in a small shop, or outdoors, crafting raw materials into products or growing a crop from seed to table. When they took factory jobs, they were working for a large company. The repetitive work often involved only one small step in the manufacturing process, so the worker did not see or appreciate what was being made; the work was often dangerous and performed in unsanitary conditions. Some women also entered the workforce, as did many children. Child labor became a major issue.

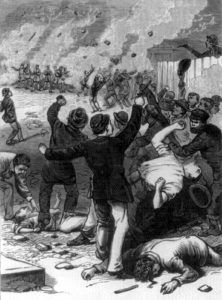

Dangerous working conditions, long hours, and concern over wages and child labor contributed to the growth of labor unions. In the decades after the Civil War, workers organized strikes and work stoppages that helped to publicize their problems.

One especially significant labor upheaval was the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Wage cuts in the railroad industry led to the strike, which began in West Virginia and spread to three additional states over a period of 45 days before being violently ended by a combination of vigilantes, National Guardsmen, and federal troops. Similar episodes occurred more frequently in the following decades as workers organized and asserted themselves against perceived injustices.

The new jobs for the working class were in the cities. Thus, the Industrial Revolution began the transition of the United States from a rural to an urban society. Young people raised on farms saw greater opportunities in the cities and moved there, as did millions of immigrants from Europe. Providing housing for all the new residents of cities was a problem. Many workers lived in urban slums, where open sewers ran alongside the streets, and the water supply was often tainted, causing disease. These deplorable urban conditions gave rise to the Progressive Movement in the early 20th century, which would result in many new laws to protect and support people, eventually changing the relationship between government and the people.

Compiled Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2021.

Also See:

American History Photo Galleries

Industrial American and the Progressive Era Timeline, 1876-1929

Sources: