Fort Ashby was built during the French and Indian War in the Patterson Creek Valley of West Virginia.

In the late summer and early fall of 1755, settlers in the Patterson Valley were attacked by marauding bands of hostile Indians. In response, on October 26, 1755, Colonel George Washington ordered three forts to defend the Western Virginia frontier – Forts Ashby, Sellers, and Cocke

Fort Ashby, which took its name for its first commander, was built by Lieutenant John Bacon and his men from Fort Cumberland, Maryland. The fort was a square stockade of 90 feet on each side with bastions at each corner. Within the fort were barracks and a powder magazine.

It was completed in about six weeks and Captain John “O.C.” Ashby took command of the fort, which was garrisoned by about 30 men. Ashby was ordered to remain quiet as long as he could and to hold the fort as long as possible, but if necessary, he was to burn it rather than surrender it.

Although the fort was initially intended to protect the area’s residents, the valley was virtually abandoned by the time of its occupancy. The fort protected the supply line between Fort Loudoun in Winchester, Virginia, and Fort Cumberland in Maryland.

From the outset, Captain Ashby was beset with personnel problems that appeared to stem from a failure to enforce discipline. On December 20th, ten of his troops informed him they were going home and then summarily left the fort. When this news reached Fort Cumberland, Captain Charles Lewis, with 22 men, was sent to investigate on December 27. Lewis found the fort in poor condition for defense and the soldiers surly and undisciplined. They also found that rum was being sold to the soldiers by a man named Joseph Coombs, yet it appeared the liquor actually belonged to Ashby. However, the troops’ main complaint was Ashby’s wife’s misbehavior. As a result, George Washington wrote a letter to Ashby stating that his wife sowed sedition among the men and was the leader of every mutiny. He also firmly instructed Ashby to immediately remove her from the fort, or he would personally drive her out himself.

In the meantime, Captain Charles Lewis took control of the post, and the Articles of War were read to the troops. After several weeks, Ashby resumed command and had gained control of his wife’s activities, for there is no record that Washington enforced his threat to “drive her out.”

However, Ashby was still plagued with troubles caused by unruly soldiers. On March 29, 1756, he had 40 men in his command when ten of them unceremoniously walked off to join Colonel Stephen’s command at Fort Cumberland.

In April 1756, a large band of Indians descended on Patterson’s Creek and surrounded Fort Ashby. They demanded a parlay at which they wanted the fort to surrender. However, Captain Ashby refused to give them a dram of whiskey, and the Indians soon departed. These Indians may have been the ones who inflicted a disastrous defeat on the Virginia Regiment forces stationed at Fort Edwards just a few days later.

By May 1756, Indian attacks in the area prompted the Virginia House of Burgesses to approve funding to erect a “chain of forts” that would stretch from the Potomac River to the Mayo River, a span of nearly 500 miles. Fort Ashby was made a part of the defensive chain. At that time, Washington ordered Colonel Adam Stephen at Fort Cumberland, Maryland, to keep Forts Ashby and Sellers well supplied with food and ammunition.

In late July 1756, a courier from Winchester arrived at the fort carrying dispatches for Colonel Washington, who was then at Fort Cumberland. Because the area was so dangerous due to hostile Indians, he requested a soldier escort. Ashby sent Lieutenant Robert Rutherford with about 16 rangers and militiamen along with the messenger to Fort Cumberland, about 12 miles distant. Along the way, they were suddenly fired upon by a band of Indians lying in ambush, at which time the militiamen turned a fled back to Fort Ashby without even firing a shot. Vastly outnumbered, Rutherford and the ranger remnants had no choice but to follow the panicked militia.

Upon hearing of the affair, George Washington, who had little respect for militiamen to begin with, was disgusted. At one time, he stated, “they are obstinate, self-willed, perverse, of little or no service to the people, and very burdensome to the country.” But, in this case, Washington’s chief criticism was directed at Ashby and his officers because they failed to properly control their men.

On one occasion, when Captain Ashby was outside the fort without his rifle, he unexpectedly came upon three Indians. He quickly fled as shots were fired upon him and obtained the fort’s safety.

In April 1757, George Washington ordered the Virginia militia to abandon Fort Ashby and Fort Cocke, as he could no longer provide enough troops. By that time, the area had been abandoned by settlers.

British General John Forbes

The fort was regarrisoned in 1758, when a force of 6,000 soldiers, led by British General John Forbes, including those from Virginia’s frontier Forts and other colonies, formed in 1758 to take Fort Duquesne, Pennsylvania. At that time, the fort was again tasked with protecting the supplies and dispatches that moved along the road between Winchester and Fort Cumberland.

At the successful conclusion of this campaign, the region was stabilized, and the fort was closed again. Afterward, it was used intermittently until the end of hostilities in 1763.

In hindsight, Fort Ashby was poorly located, as the nearest stream was 200 yards to the west and was dominated by a hill to the south, from where the enemy could have fired into the stockade. Its chief value had been escorting convoys and messengers along the military road leading from Fort Loudoun at Winchester to Fort Cumberland and on roads leading north the Will’s Creek and south to Fort Cocke, twelve miles away. In fact, Washington would later say that this was the fort’s only value.

Though records suggest that Captain John Ashby was inept in his role, he continued to serve as a military leader until the end of the French and Indian War in 1863. He also remained on friendly terms with George Washington. After the war, he returned to his home in the Shenandoah Valley, where he operated a ferry across the Shenandoah River for many years.

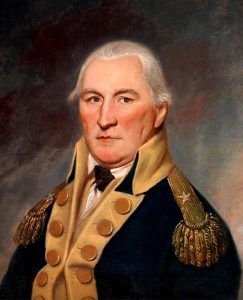

Major General Daniel Morgan

After the fort was officially abandoned, it was periodically manned by local militia.

In October 1794, the old Fort Ashby was again the scene of military activity when Major General Daniel Morgan, with 500 or more troops, encamped around the fort while awaiting orders to proceed during a tax-related protest known as the Whiskey Rebellion. Over the next few days, more than 1,200 more troops joined the others a Fort Ashby before moving on to western Pennsylvania. This army of more than 1,700 men was by far the largest number of military personnel ever to assemble in the area, and the settlers would see no more armed troops of such great numbers until the outbreak of the Civil War 67 years later.

In the meantime, a settlement was established around the fort, which was first called Frankfort. Later the town’s name was changed to Alaska, and finally, the community took its name from the old military post and became Fort Ashby.

A portion of the log barracks was converted into a dwelling and was used as such for more than 130 years. In 1927, the building was bought by the

Potomac Valley Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and in 1935, it was conveyed to Mineral County for restoration purposes. Through the assistance of the Works Progress Administration, the Fort was restored in 1938 and opened as a museum to visitors the next year. In 1970, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

More Information:

Fort Ashby

227 Dan’s Run Road

Fort Ashby, West Virginia 26719

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Also See:

Forts & Presidios Across America

Sources:

Ansel, William H., Jr.; Frontier Forts Along the Potomac and its Tributaries; McClain Print. Co., 1984

Fort Ashby

Terry Gruber

West Virginia Public Broadcasting