The Call Building in San Francisco, California, was once the tallest and was renowned for its beauty. Though the building was not demolished, it underwent a facade renovation in the 1930s, leaving it unrecognizable. Today, it is called Central Tower, a name as bland as the building itself.

By the late 19th century, San Francisco was undergoing a significant transformation to a world-class city after leaving its pioneer beginnings behind. Its citizens strived for the best, building fine hotels, great restaurants with unique cuisines, and new buildings that reflected wealth and power.

In 1890, Michael H. de Young, the owner of the San Francisco Chronicle, built the city’s first skyscraper, the 218-foot Chronicle Building, to house his newspaper. In response, Claus Spreckels, a wealthy businessman with whom de Young had been feuding, bought the very successful San Francisco Call newspaper in 1895, intending to bring down de Young and the Chronicle. The same year, Claus and his son, John D. Spreckels, commissioned another building to eclipse the 10-story Chronicle Building.

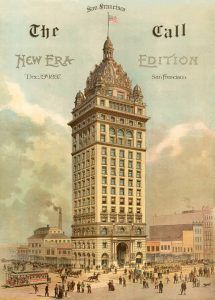

In September 1895, the Call wrote:

“The San Francisco Call is to have the finest building ever erected for a newspaper office. It is to be built on the corner of Market and Third streets, of granite and white marble, and will be fifteen stories — 310 feet high, the highest building this side of Chicago. Unlike the Chronicle building, it will be a beautiful building and a credit to its owner, Claus Spreckels, and worthy of the great paper to be printed within its walls. A light granite will be used for the first three stories, but above the third story, white marble will be used. The main entrance or rotunda will be finished in some polished California marble, the very choicest obtainable, and the floor will be mosaic.”

Aware of the earthquake risks, the Spreckels hired noted local architects James and Merritt Reid and nationally recognized bridge engineer named Charles Strobe, who had invented the Z-bar structural steel design. In September 1895, the first ceremonial shovel of dirt was removed from a 70 feet x 75 feet lot at the corner of Third and Market Streets. Soon, a large base was laid 25 feet below street level to support and stabilize the structure.

By the end of 1897, Claus Spreckels had spent over $1 million on constructing his new building, almost all of which was spent on local labor and materials. At 310 feet tall, the lower portion of the building was 15 stories, topped by a dome that housed the 16th through the 18th floors.

The ornate terra cotta dome and its corner cupolas defined its baroque architectural style. This style exemplifies royalty, permanence, and power, which is exactly what Spreckels wanted to achieve.

The interior was as modern and elegant as the facade, featuring maple floors, window frames, and doors made of hardwood. All offices featured polished oak wainscoting. The marble dome of the lobby had a mosaic floor with a circular motif bearing the monogram “CS.” This motif was repeated on every doorknob in the building as well as on three bronze doors. The building was one of the first to use electricity as its sole source of lighting. Elevators served the building from lobby to dome, ascending to the 19th floor in less than a minute.

On the evening of Friday, December 17, 1897, crowds were treated to a spectacular light show to celebrate the city’s newest attraction — the tallest building in San Francisco, on the Pacific Coast, and west of Chicago.

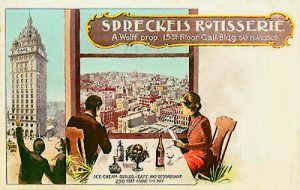

By early 1898, offices in the Call Building housed many prominent men and businesses, including attorneys, bankers, accountants, and other men of commerce who paid premium rent for space. On the 15th floor was the Spreckels Rotisserie, which boasted some of San Francisco’s finest cuisine. Spreckels hired some of the finest chefs, who provided a seven-course dinner with wine that cost $1.00. Advertising invited tourists and San Franciscans to “dine in the clouds” and see the city from a unique vantage point.

In the dome, the 16th and 17th floors were reserved for the San Francisco Club meetings, whose president was Adolph Spreckels. The 16th floor housed a private dining room finished in marble, glass, bronze, and mahogany, which could host 200 guests, while the 17th floor was reserved for meetings. The Reid brothers architectural firm occupied the 18th floor, which provided 12 porthole windows that provided panoramic views of the city. There was also a small 19th floor that provided storage and housed the Call Lantern — a red light signaled an extra edition was coming.

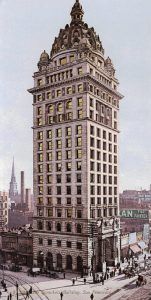

The ornate Call Building in San Francisco was completed in 1898. Though it still exists today, its beauty has been stripped, and it is unrecognizable. Photo by Detroit Photographic, 1905.

One admirer, who remains unknown today, wrote of the building:

“It is, per se, a beautiful building–that is the unanimous verdict. After that, it is imposing, magnificent, costly, a pride to San Francisco, a monument to the good taste and enterprise of its owner and builder, Claus Spreckels; the greatest newspaper building in the world, the handsomest of tall buildings, the tallest of the tall buildings west of Chicago–all these things and more; but first, last and all the time, it is the most beautiful building.”

The building and the newspaper were a success, but tragedy met them when San Francisco was rocked by a series of devastating earthquakes beginning on the morning of April 18, 1906. While the Call Building withstood the earthquake, several fires broke out across the city, and the Winchester Hotel behind the Call building succumbed to the flames. As the fire continued to spread, it reached the third floor of the Call Building, burning through a suite of offices and reaching the corridor and the elevator shafts. The blaze began to rage through the elevator shaft, which acted as a huge flue, and the fire raced through the center of the building, even blowing out the round windows of the tiny 19th floor in the dome. The fire continued through the rest of the building, blowing out windows on each level as spectators watched from the street. Within just two hours, the city’s most famous structure was a smoldering shell.

However, its structure was still sound, and within a month, the lower floors of the building had been reopened while workers made extensive repairs to the upper stories. Scaffolding covered the building for more than a year as the rest of the building was refurbished. By the time Claus Spreckels died in 1908, the building was complete, and his sons then took over his business. However, his son John moved his family to San Diego to pursue other business opportunities, and his son Adolf was in ill health.

The San Francisco Call newspaper was sold to Michael H. de Young, the owner of the San Francisco Chronicle, in 1913, and, at some point, the Call Building was also sold.

In the 1930s, the building was purchased by investors, and after architect Albert Roller learned that the structure would easily support six full stories above the 15th floor, plans were made for extreme changes. In 1937, the baroque dome was seen as “uneconomical” and replaced with floors in a square style. The entire building also went through more “modern” changes reflecting an Art Deco style that was popular at the time. He modified the entrance, lobby, and elevators with the classic art deco adornments, which he felt would bring the building into the 20th century. When it was complete, the building included 21 full stories of usable, rentable office space, even though the building’s height was reduced to 298 feet. In the meantime, the terra cotta ornaments, including decorative friezes, columns, arched windows, and other “inefficient” ornamentation, were removed and discarded.

Central Tower in San Francisco was formerly the Call Building before it was refurbished in the 1930s. Photo by Phliar-Flickr.

The whole building was refaced with cream-colored concrete, creating a severe, unadorned vertical shaft. The interior offices and corridors were also “modernized” with interior marble stairs, and the arches and columns in the lobby were removed. Polished black marble floors, bronze Art Deco motif elevators, and curved glass brick walls were acclaimed as a feat of remodeling. Though success might have been found in an Art Deco style on the inside, the outside was bland, unadorned, and boring.

The structure then took on the name of the Central Tower, which continues to stand at the corner of Third and Market Streets. But, what was once called the “handsomest commercial edifice in the world” is now just one more downtown building. Today, its former glory exists only in vintage photographs.

While Claus Spreckels won the short-term battle of buildings and newspapers, he lost the war in the end. His San Francisco Call newspaper was purchased by his enemy Michael H. de Young, the owner of the San Francisco Chronicle, in 1913. Over the years, it was sold several times and went by various names before the San Francisco Examiner purchased it in 1965, and the “Call” name was discontinued.

The San Francisco Chronicle is still in publication today, though it moved to a new location at Fifth and Mission Streets in 1924. Afterward, the old Chronicle Building became a typical office building. In 1962, it too was modernized with a new facade of aluminum, glass, and porcelain paneling. The Old Chronicle Building was designated as a San Francisco Landmark in 2004 and became the Ritz-Carlton Club and Residences in November 2007.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Lost Historic Landmarks and Vanished Sites

Sources:

San Francisco City Guides

San Francisco Found

San Francisco Love to Know

Wikipedia