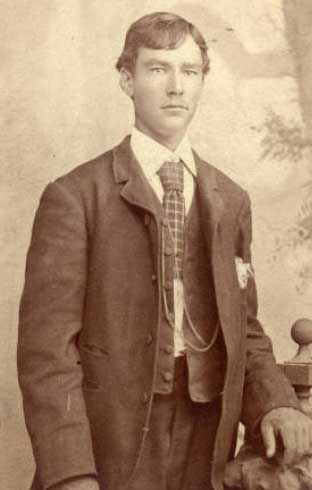

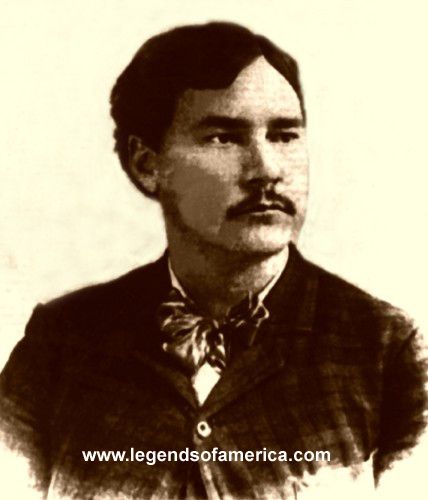

Elfego Baca 1883

By Jesse Wolf Hardin

“I will show the Texans there is at least one Mexican in the county who is not afraid of an American Cowboy.” — Elfego Baca, 1884

The tiny hamlet of Reserve, New Mexico, lies almost a hundred miles north of Silver City in the state’s mountainous southwest, adjacent to the Gila: this country’s first protected wilderness. While lately characterized by its world-class elk hunting and the county’s outspoken resistance to federal lands policies, the bucolic Catron Country village of Reserve was once better known as the site of the fabled “Frisco War.” In a dramatic display of skill, spunk, and luck, an unimposing 5′ 7″ Hispanic named Elfego Baca instigated and prevailed in what was likely the most unequal gunfight in the history of the American West.

Elfego Baca

This singular battle has long served as a symbol of the power of the lone individual, standing up against overwhelming odds for what they happen to believe is right. For some folks at the turn of the century, this meant the “sod-busting” granger taking a stand against big-moneyed Eastern ranching interests. More recently, the oft-told siege has been adopted by small-time ranchers seeking to hold onto their livelihoods and lifestyles in the face of increasing government regulation and economic downturns. Still, others see the spirit of Elfego in the most powerless of the disenfranchised: those species of wildlife facing extinction and waging their own battle for survival. And for the lay historian, the odds Baca faced evoking not only Gary Cooper in “High Noon” but the ragtag army of the original 13 colonies resisting the might of the British empire, the tiny phalanx of Spartans holding the pass of Thermopoli against the pressing Persian hordes, and the boy David boldly facing a giant Goliath… swinging a modest sling with all his might.

Residents of the rural West, in the 1800s as now, seem to share a common grit: a way of being born of a certain wildness nursed on freedom and raised in intimate contact with the natural world. The early West’s lawbreakers and those appointed to “bring them to justice” were generally rugged, earthy individualists. Folks on either side of the badge often considered themselves refugees from the constraint and propriety of an ever more perplexing urban society. Both were quick to resort to gunplay’s decisiveness, ignore the law’s finer points, and pursue their whims and agendas with a vengeance. Not to mention with particular humor and flair.

And surely none more so than our man Baca delivered on the softball field of Socorro, Territory of New Mexico, in February 1864. Local legend has it he was kidnapped by renegade Indians at the age of one and then promptly returned.

He later cited this affair as another example of his lifelong good fortune, but if true, the incident may say more about his native incorrigibility. Any way you toss it, Elfego grew up into one “tough bite to chew.” At the age of twelve, he may have helped his father (and consequently several other, less savory inmates) to escape from the freshly built Socorro jail by sawing through the ceiling of their cell. Much later in life, while serving as a Sheriff himself, he is said to have reversed the procedure by coaxing various wanted men with a simple correspondence: “Dear Sir… Please come in on (whatever date) and give yourself up. If you don’t, I’ll know you intend to resist arrest, and I will feel justified in shooting you on sight when I come after you. Yours truly, Elfego Baca”). Legend and fact intertwine in uncertain ways in that place we’ve come to call the Wild West. What is certain is that during the three days of October 29th through the 31st, 1884, Baca managed to survive the murderous intent of nearly a hundred irate cowboys.

While nearly everyone knows something about Wyatt Earp and the world-famous O.K. Corral, few in this country have heard of New Mexico’s Gila country or the once-celebrated antagonist of the Frisco siege. Odd, considering that the famous Tombstone shootout rather fairly matched four men against five, involved less than a dozen rounds fired altogether, and lasted only three-fourths of a minute… while the “Frisco War” pitted a single person against something over eighty armed antagonists, hundreds or thousands of shots were exchanged, and the confrontation lasted over thirty-three hours! The walls of the flimsy structure where he’d taken refuge were splintered from the constant firing, with one report claiming there were three hundred and sixty-seven perforations of the door alone. Even forks and knives were hit, with the courtroom audience appropriately aghast at the humble broom brought in as evidence. A broom with eight bullet holes in its slender handle!

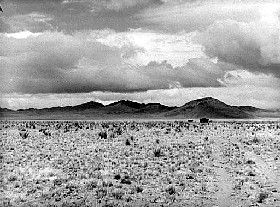

Gila County, New Mexico

This region was first the home of the Mogollon Indians until they migrated down into the Rio Grande basin sometime around 900 A.D. The Apache was next to arrive, who came to consider the greater Gila as their “sacred hunting ground.” By the 19th Century, it had become the staging ground for the last of the Indian wars, with anglo miners and trappers exploring the area tributaries and several hundred Spanish-speaking families farming alongside every slow wandering river. Before long, the Middle and Lower Frisco villages could boast over a dozen bars and bordellos, each catering to the influx of cattlemen arriving daily from Texas and Oklahoma. The valley became rife with tension due to Apache raids to the south and various altercations between the cattle outfits and the Hispanic community that preceded them. “What happened next, “historian Jack Ritdron notes, “was only a logical consequence.”

In October 1884, the 19-year-old Elfego may have been approached in Socorro by his friend, the sheriff of Lower Frisco, Pedro Sarracino. The sheriff recounted a tale of terror to him, wherein the Hispanic community suffered at the hands of a group of drunken cowpokes. Baca claims to have chastised Sarracino for his hesitancy, who supposedly replied that his job was “available to anyone who wanted it” before retiring to the solace of the nearest bar.

In Baca’s memoirs, he claims he next pinned on a phony kid’s badge before beginning the long ride to Frisco, while other participants insisted he was already a legally sworn deputy at the time, campaigning in the area for the current Socorro County Sheriff. Either way, it could be said that Elfego Baca entertained more guts than caution, charging headlong into a situation he knew little about. Strapped to his side was a Colt .45, a coat draping over its characteristic black resin grips.

Soon after his arrival on the 29th, a cowboy named Charlie McCarty decided to celebrate the good life with a shooting spree inside a bar in the Upper Frisco Plaza. The owner was an Irish-blooded army vet named Bill Milligan, who first requested Baca’s assistance in the matter. Convincing three local Hispanics to help, Baca quickly caught up with McCarty and disarmed him, sticking the unfortunate sod’s loaded revolver into his own belt. Their new prisoner hailed from a notoriously rowdy outfit at the John B. Slaughter ranch, who were none too happy to hear this self-appointed hero had snagged their boy. When the local magistrate proved too intimidated to try the case, Baca considered taking him to Socorro. Meanwhile, he and his friends would move McCarty to an adobe house in the Middle Plaza where it would be easier to maintain possession of their prisoner.

By this time, a dozen or so cowboys had gathered with their Winchester rifles at ready, led by Slaughter foreman Young Parham. They immediately demanded their buddy’s release, testing the door and windows with their shoulders. Baca responded from the other side, threatening to shoot if they weren’t “out of there by the count of three.” The story is that they were in the process of making jokes about his type “being unable to count” when they heard Baca call out in a single quick breath: “One-two-three!” while he and his friends began shooting through the door. In their haste to escape this lesson in rapid arithmetic, Parham’s horse reared back and on top of its rider, resulting in wounds that would later prove fatal.

Socorro County, New Mexico

Word of a “Frisco War” promptly spread to the outlying ranches, including those of the well-known James H. Cook and the Englishman William French. After receiving a signed agreement that he wouldn’t be bothered, Baca agreed to allow his prisoner to be “tried” at Milligan’s Bar the following morning. McCarty was fined five dollars and released, complaining about not getting his revolver back even as the prudent Baca began backing out the side door and chasing out the residents of the nearby Armijo jacal. Pronounced ha-call, Baca’s temporary fortress was typical of the one-room buildings found scattered throughout the valley. Made of thin cedar poles stuck into the ground and coated on both sides with an adobe (mud) slip, its walls would offer little resistance to the concerted attack he expected to follow.

Rumors flew throughout the neighboring regions of an “uprising” of the Hispanic population against the stockmen until the growing mob felt emboldened to seek their revenge. A roper known as Hearne was the first to chance the door, kicking at it and screaming that he’d “get” Baca. He was answered most poignantly by twin 250-grain slugs, one of which caught Hearne solidly in the gut and sent him to the ground. The cowboys responded with what became a steady volley of rifle fire, lobbing rounds from nearly every angle. The quickly gathering mob failed to realize that the floor of Baca’s insubstantial-looking refuge had been dug down a full foot and a half below ground level. He was thus enabled to coolly return fire with his single-action handguns even as lead rained through the space above.

While most of the town climbed up on the overlooking hills to watch, a group of the attackers stretched blankets between the nearby houses to conceal their movements, and others fired from behind the buttress of the adobe church. One brave attacker fell back with his scalp neatly creased by a bullet after attempting to approach the jacal with an iron stove door for a shield. Finally, as day turned into night, they could toss flaming kerosene-soaked rags onto the dirt and latilla (branch) roof. One wall gave way under the combined assault of lead and fire, causing a portion of the roof to collapse on the hapless defender.

They were pretty sure they’d “fixed his wagon” by this time but opted to err on the side of caution, deciding to wait until the following day to try and dig him out. Come the first gray light of dawn; they were surprised, mortified even, by the thin wisps of smoke rising from the perforated woodstove. To one end stood a plaster statue of the Nuestra Señora Doña Ana, while at the other end, the unruffled Baca nonchalantly flipped his breakfast tortillas! The battle immediately regained its former intensity, with both Elfego and the stoic Señora remaining miraculously unscathed.

When at last, James Cook and the newly arrived Deputy Ross of Socorro convinced Baca to come out, personally guaranteeing his safety, some of the Hispanic spectators yelled for him to run. With both guns in hand and every cowboy’s rifle trained on his chest, Elfego slowly approached to make his truce. Yes, he would surrender… but only if he could keep his weapons, travel in the back of a buckboard with his and McCarty’s Colts, and with all accompanying cowhands keeping at least 30 feet behind them for the entire trip to the Socorro courthouse! The ever-blessed Elfego even missed an ambush planned for him on the route when two different groups of avengers each mistakenly thought the other had carried out the mercenary deed. In jail for only four months, Elfego was tried on two separate occasions and was surprisingly acquitted each time.

Nearly everyone writing about this affair has accepted Baca’s personal tally of battle casualties: four men killed and eight wounded. A close look at every other historical source indicates that only one attacker actually died from gunfire, with a second killed by when his own horse fell on him. Likely the poor fellow with the bullet through the knee was the only one with a significant non-fatal wound. Regardless, the Frisco War remains the most astoundingly unequal civilian gunfight ever recorded. And a source of conversation and metaphor still.

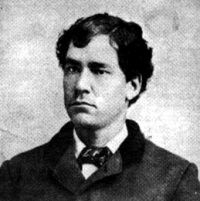

Elfego Baca

It was the Frisco shootout that earned Elfego, his lifelong reputation as a tough hombre. This reputation followed him throughout his years as a flamboyant criminal lawyer, school superintendent, district attorney, chief bouncer of a Prohibition Era gambling house in Juarez, and about as the American agent for General Huerta during the convoluted Mexican revolution.

Elfego Baca 1927

For over 80 years, Elfego Baca remained a lively part of New Mexico’s cultural landscape, telling spirited stories of cagey señoritas and political intrigue to anyone with the time to listen. He was one of those who lived through the last half of the 19th Century and survived the first half of the 20th. In the year of Elfego’s delivery to an unsuspecting world, horses were the primary means of transportation, even in the more civil East. He died as eight-cylinder roadsters zoomed by outside his Albuquerque office on August 27, 1945… exactly three weeks after the first-ever wartime deployment of a nuclear weapon.

Like Elfego before them, the current residents of this rurality demonstrate a tenacious ability to survive the machinations of the modern world, hanging on to this challenging and stunningly beautiful land the way the juniper trees cling to the sides of the sandstone cliffs. Newly arrived nature lovers and fifth-generation ranchers share more in common than they may care to admit. They join a history of devout Mormon settlers as well as unrepentant outlaw sinners, Texas and Oklahoma cowboys and Hispanic homesteaders, the ghosts of the Mogollon Indians, and the spirits of those yet unborn… in devoting themselves to a place… a place known to evoke not only beauty but freedom. Here the land that lived before our kind, the land that will outlive one’s mortal life, speaks in a language unaltered by either man or time. And the stories of the West’s diverse peoples and wild characters still breathe in its winds and rivers, as in their poignant campfire telling.

© Jesse L. “Wolf” Hardin, 2006, updated November 2022.

About the Author: Elfego Baca & The “Frisco War” is adapted from Jesse L. “Wolf” Hardin’s popular book Old Guns & Whispering Ghosts which includes several fascinating stories of the colorful characters and firearms of the wild West, as well as dozens of previously unpublished historical photos. Hardin is a lifelong student of Western history and antique firearms and a prolific artist, entertaining Old West presenter, and storyteller. In addition to Old Guns & Whispering Ghosts, he has published four other books and numerous articles in more than 100 magazines. Hardin, who lives in an isolated canyon in the Gila Mountains of southwest New Mexico, also tends to a wildlife sanctuary. To learn more about Jesse Hardin and his newest book, visit his website: http://www.oldgunsbook.com

Also See:

Adventures in the American West