The Wounded Knee Massacre, a regrettable and tragic clash of arms occurring on December 29, 1890, was the last significant engagement between Native Americans and soldiers on the North American Continent, ending nearly four centuries of warfare between westward-bound Americans and the indigenous peoples.

The event was precipitated by individual indiscretion and was not organized premeditation, and although the majority of the participants on both sides had not intended to use their arms, the tense and confusing situation ended tragically. After the haze of gun smoke that hung over the battlefield was cleared, some of the facts have been obscured, but the action more resembles a massacre than a battle. Today, it serves as an example of national guilt for the mistreatment of the Indians.

The arrival of troops on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota to quiet the Ghost Dance disorders of 1890 provided the climate for the massacre. After Indian police killed Chief Sitting Bull while trying to arrest him on December 15 on the Standing Rock Reservation, his Hunkpapa band of the Lakota tribe grew agitated, and troop reinforcements arrived.

When 200 of the Indians fled southward to the Cheyenne River, military officials feared a Hunkpapa-Miniconjou coalition. Most of the Standing Rock fugitives allied for a time with the Miniconjou Chief Hump and his 400 followers before joining them in surrendering at Fort Bennett, South Dakota.

About 38 of the Hunkpapa joined a more militant group of 350 or so Miniconjou Ghost Dancers led by Chief Big Foot. After a few days of defiance, Big Foot, ill with pneumonia, informed military authorities he would surrender. When he failed to do so at the appointed time and place, General Nelson A. Miles ordered his arrest. On December 28th, a 7th Cavalry detachment under Major Samuel M. Whitside intercepted him and his band southwest of the badlands at Porcupine Creek and escorted them about five miles westward to Wounded Knee Creek. In this place, Big Foot said he would surrender peacefully. Early that night, Colonel James W. Forsyth arrived to supervise the operation and movement of the captives by train to Omaha, Nebraska, via the Pine Ridge Agency. His force, totaling more than 500 men, included the entire 7th Cavalry Regiment, a company of Oglala scouts, and an artillery detachment.

U.S. Troops surrounded the battlefield at Wounded Knee, re-enactment photo by James A. Miller, 1913.

The disarming occurred the next day. It was not a wise decision, for the Indians had shown no inclination to fight and regarded their guns as cherished possessions and means of livelihood. Between the teepees and the soldiers‘ tents was the council ring. On a nearby low hill, a Hotchkiss battery trained its guns directly on the Indian camp. The troops, in two cordons, surrounded the council ring.

The warriors did not comply readily with the request to yield their weapons, so a detachment of troops went through the teepees and uncovered about 40 rifles. Tension mounted, for the soldiers had upset the teepees and disturbed the women and children, and the officers feared the Indians were still concealing firearms. Meanwhile, the militant medicine man, Yellow Bird, had circulated among the men, urging resistance and reminding them that their “ghost shirts” made them invulnerable. When the troops attempted to search the warriors, the rifle of a man named Black Coyote, considered by many members of his tribe to be crazy, apparently discharged accidentally when he resisted. Yellow Bird gave a signal for retaliation, and several warriors leveled their rifles at the troops and may have even fired them. The soldiers, reacting to what they deemed to be treachery, sent a volley into the Indian ranks. In a brief but frightful struggle, the combatants ferociously wielded rifles, knives, revolvers, and war clubs.

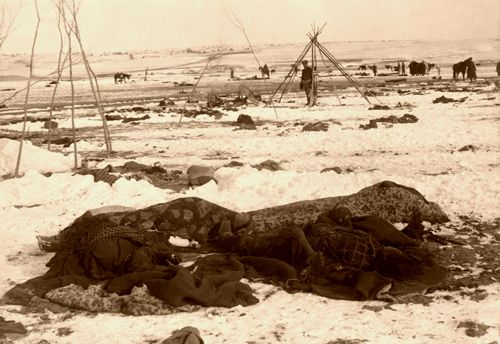

Soon, the Hotchkiss guns opened fire from the hill, indiscriminately mowing down some of the women and children who had gathered to watch the proceedings. Within minutes, the field was littered with Indian dead and wounded; teepees were burning; and survivors were scrambling in a panic to the shelter of nearby ravines, pursued by the soldiers and raked with fire from the Hotchkiss guns. The bodies of men, women, and children were found scattered for a distance of two miles from the scene of the first encounter. Because of the frenzy of the struggle and the density of the participants, coupled with poor visibility from gun smoke, many innocents met death. In the confusion, both soldiers and Indians undoubtedly took the lives of some of their own groups.

Of the 230 Indian women and children and 120 men at the camp, 153 were counted dead and 44 wounded, but many of the wounded probably escaped, and relatives quickly removed a large number of the dead. Army casualties were 25 dead and 39 wounded. The total casualties were probably the highest in Plains Indian warfare except for the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The battle aroused the Brules and Oglala on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations. By January 16, 1891, troops had rounded up the last of the hostiles, who recognized the futility of further opposition.

Following the massacre, the soldiers left the wounded Native Americans to die in a three-day blizzard that followed and later hired civilians to remove the bodies and bury them in a mass grave.

Afterward, the soldiers lined up and had their picture taken beside the mass grave. Twenty medals of honor were later given to honor the U.S. soldiers who participated in the massacre.

However, one officer, General Nelson Miles, denounced Colonel Forsyth and relieved him of command. Though an Army Court of Inquiry criticized Forsyth for his tactical dispositions, they otherwise exonerated him of responsibility, and Forsyth was reinstated. Even so, Miles continued to criticize Forsyth and promoted the fact that Wounded Knee was a deliberate massacre.

In addition to the many who were killed in the massacre, the Sioux Nation, as it was known, died there too. By then, its people fully realized the totality of the white conquest. Before, despite more than a decade of restricted reservation life, they had dreamed of liberation and a return to their fathers’ life mode — a sentiment strongly manifested in the Ghost Dance religion. But, the nightmare of Wounded Knee forced reality upon them. They and all the other Indians knew that the end had finally come and that conformance to the white men’s ways was the price of survival. It was perhaps not purely coincidental that the same year as Wounded Knee, the U.S. Census Bureau noted the passing of the frontier.

In 1903, a monument was erected at the site of the mass grave by surviving relatives to honor the many innocent women and children who were killed in the massacre. Later, Native American activists urged the U.S. government to withdraw the medals officially but were unsuccessful. However, in 2001, the National Congress of American Indians passed two resolutions that condemned the Medals of Honor awards and again called on the U.S. Government to rescind them.

The battlefield was designated a National Historic Site on December 21, 1965, and though modern buildings and a road system have scarred and fragmented it, it remains an impressive reminder of the last major military-Indian clash.

Located on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, the site displays a series of markers that interpret the massacre and a privately operated museum that displays battlefield artifacts. Standing atop a low hill on the approximate site of the Hotchkiss battery is a simple white frame church, behind which is the cemetery, which includes the mass grave of the Indians who died in the battle and the 1903 monument. The site is owned privately by individuals and the Sioux tribe.

The battlefield is located on a secondary road about 16 miles northeast of the town of Pine Ridge.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Also See:

The Ghost Dance – A Promise of Fulfillment

Lakota, Dakota, Nakota – The Great Sioux Nation

Military Campaigns of the Indian Wars

Source: National Park Service