By Paris Permenter and John Bigley

Texas Hill Country

A man in soiled clothes quickly throws another shovelful of dirt over his shoulder. His face glistening with the sheen of sweat, he works faster and faster, listening all the while for distant hoofbeats. He can’t let anyone see him–he has something to hide.

Texas has more buried treasure than any other state, with 229 sites within the state’s borders. The total value? An estimated $340 million. And much of this treasure lies under the rugged oaks and rocky landscape of the Texas Hill Country. There are many stories behind this area, some that have been told for generations and many that may remain secrets taken to the grave by the original treasure owners.

The search for buried Hill Country treasure begins at its edge, in the community of Round Rock. Here, outlaw Sam Bass hid from the law until a final shootout with the Texas Rangers on July 19, 1878. Bass was in Round Rock making plans for a bank robbery. Before he died; however, many say that he hid much of the loot from his train, stagecoach and bank robberies somewhere in the area.

One of the most common tales is of a loot hid in an old tree by the outlaw. The legend began several years after Bass’ death, when maps leading to the alleged treasure appeared. The location was said to be in a hollow tree on what is now the Sam Bass Road, about two miles west of Round Rock. A tree similar to the one described on the map was spotted by treasure-hunters and chopped down–only to come up empty. Optimistic treasure seekers still wonder–could earlier searchers have chopped down the wrong tree?

The Sam Bass legends are not the only treasure-filled stories flying around Williamson County. One treasure story dates back to an ancient Spanish document regarding an old Spanish mine, located somewhere near Burnet. According to an Austin American story in the early 1920s, a “pack train of burros carrying 40 jackloads of silver was pursued by a band of Comanche Indians and … the men in charge of the pack train buried the silver near where the town of Leander is now located.”

No one’s found the Spanish silver cache, but some treasure seekers in this area have struck gold–or gemstones, as the case may be. In 1925, W.E. Snavely of Taylor, who had hunted treasure for 60 years, found a ruby arrowhead weighing 15 karats, along with many other gemstones.

Heading west, back into the heart of the Hill Country, lie a number of treasure sites. Longhorn Caverns, outside Burnet, is said to be the home of more than one treasure trove. One tale involves who else but Sam Bass, who allegedly used the cavern as a hide-out following nearby robberies. Today the main opening of the cave is called the Sam Bass entrance. No Bass treasure has been found, but even today, parts of the 11-mile cavern are still being explored.

Another Longhorn Cavern tale involves the search for a treasure supposedly buried on Woods Ranch near Burnet. After years of searching, one of the treasure hunters went to seek the advice of a palmist, whose cryptic recommendation was to dig “under the footprint.” There was speculation that this “footprint” might be a foot-shaped impression on the ceiling of one of the Longhorn Cavern rooms. The crew dug below this formation–only to find a container shaped hole below the surface. Where there had once been a metal container–and possibly a treasure–there was only a rust-lined hole.

Sam Bass Gang.

Moving west to Llano, we’re once again on the trail of Sam Bass. Allegedly, the robber hid canvas sacks marked “U.S.” and filled with gold in a cave on Packsaddle Mountain. Some say the treasure was found by a Mexican laborer, hired by a local rancher to cut fence posts on Packsaddle Mountain. According to one version of the story, the rancher went to look for the laborer when he failed to return to the ranch. All the rancher found was a cave, and a piece of canvas sack with “U.S.” imprinted on it. Another version of the story says the gold still lies hidden somewhere in the mountain.

Packsaddle Mountain is also the home of the Blanco Mine, named for a Spaniard who found the location long ago. According to J. Frank Dobie’s book Coronado’s Children, the mine was rediscovered in the 1800s by a Llano settler named Larimore. While hunting, Larimore discovered the old mine–with its contents of lead and a high percentage of silver.

In 1860, Larimore took a last trip to the mine with a man named Jim Rowland. The two men hauled out several hundred pounds of the metal, shaping it into bullets. Larimore, who was leaving the country, declared that he would hide the mine so well that no other person would ever find it. Supposedly, he diverted a gully directly into the mine, filling it with silt. Rowland carved his initials on a large stone marking the entrance to the mine, then covered it with earth. Where it remains today.

Llano County is home to other buried treasure sites, including $60,000 in gold and silver coins buried by Sam Bass near the community of Castell in the western part of the county. Bass buried the loot on a creek bed, marking the spot with a rock in a fork of a tree.

The trail of Sam Bass continues to near the state capital, where he allegedly buried $30,000 in the community of McNeil. No treasure was ever recovered, and today there is little remaining of the original McNeil, located in the northern part of Travis County near Round Rock.

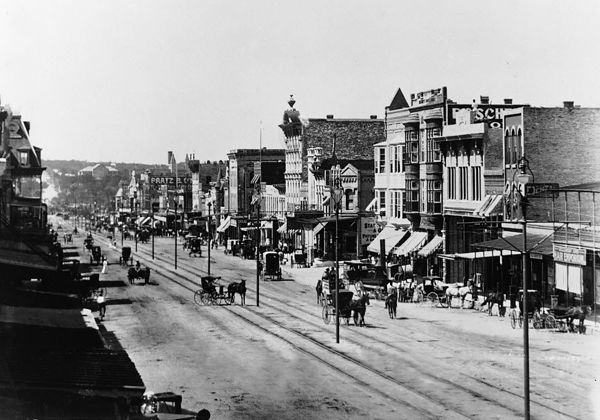

Austin, Texas, the 1800s.

The biggest treasure of all, some say $3 million dollar’s worth, is said to be buried in Austin. According to one source, this money, part of the Mexican payroll in 1836, was stolen by the paymaster, a general, and seven privates. The men took the loot near where Shoal Creek empties into the Colorado.

Greed set in, however. Two of the privates murdered their co-conspirators. Before long, one of the privates had killed the other. The remaining outlaw returned to Mexico, then found he was unable to come to Texas again. He made a map of the site, showing that it was buried five feet underground, close to an oak tree with two eagle wings carved on it.

Another source claims that the treasure was nowhere close to $3 million, actually only about $80,000 in gold coins. The story changes–instead of a Mexican payroll it substitutes Confederate money in the hands of soldiers who were afraid the Capitol would be overrun toward the end of the Civil War. According to The Rising Star Record (May 12, 1927), the treasure was purloined by workers on April 13, 1927. Working on the banks of Shoal Creek, a crew of eight men worked on a forty foot tunnel for over eight months. When questioned, they replied that they were working on “the foundation for a new bridge” and, later, “the foundation of a fine house.” A guard was kept on the tunnel at night.

On the night of April 13, “a box was lifted from the square cut chamber between the rocks, for the next day the workmen were gone and the blasting has ceased. Curious throngs soon found the dark tunnel and with lights discovered traces of the large wooden box that had laid beneath the dirt for more than 60 years.”

The treasure was gone.

The Shoal Creek treasure may be gone, but plenty of others lie beneath the surface of the Hill Country. With permission from private landowners, anyone is free to take a pick and shovel and, like generations have done in the past, search for gold.

© Paris Permenter and John Bigley, submitted 2006

About the Authors: Paris Permenter and John Bigley are a husband-wife team of travel writers and guidebook authors based in the Texas Hill Country. Paris and John run Doggone Texas an online guide to dog-friendly travel in the Lone Star State.

Also see: