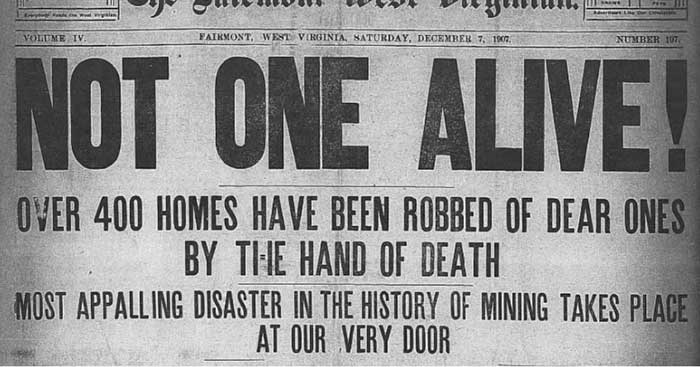

Fairmont, West Virginia Newspaper, December 7, 1907, headline for the worst mining disaster in U.S. History.

Coal mining in West Virginia has always been a risky profession, especially before 1920, when laws had not been created to improve and monitor mine safety. During those years, working as a coal miner was an extremely unhealthy and dangerous occupation.

Mining accidents occurred from a variety of causes, including leaks of poisonous gases such as hydrogen sulfide or explosive natural gases, especially firedamp or methane, dust explosions, collapsing of mine stopes, mining-induced earthquakes, flooding, and general mechanical errors from improperly used or malfunctioning mining equipment, such as safety lamps or electrical equipment. The use of improper explosives underground also could cause methane and coal dust explosions.

Other accidents occurred due to fire and smoke, cave-ins, snowslides, gas inhalation, and machinery/equipment failures such as cage falls, mine car and hoisting accidents, and others.

Once the miner was down to his working level, he contended with moving tram cars, steam lines, electric wiring, various types of machinery, and the heavy, hot, and massively vibrating drills. Supporting timber if poorly positioned, or if the wood became water-soaked and rotten, or with minor shifts in the earth’s crust, tons of rock would suddenly fall, trapping or crushing the miners.

Coal mines were often filled with odorless and tasteless methane gas. Canaries, birds that were sensitive to toxic gases such as carbon monoxide and methane, were used until the 1980s when handheld electronic detectors replaced them.

In general, early mine accidents were blamed on God or the carelessness of the miner. These attitudes on the part of the mine owners, the courts, and government agencies continued well into the 20th century.

In 1883 the West Virginia Legislature passed the first law regarding coal mining in the state. The law provided a qualified mine inspector to be appointed by the governor who appointed Oscar A. Veazey.

His job required him to prepare an annual report on the number of mines, employees, and a summary of his activities. It also required the reporting of all mine fatalities and the names of the victims, which was completed in 1883. The following year, Veazey proposed the first comprehensive mine safety laws.

Since 1883, when fatality records began to be kept, more than 21,000 miners have lost their lives in the West Virginia coal mines. In the early years, most of these deaths were single fatalities, and many were not investigated. However, in 1883, when 20 miners lost their lives, the legislature established the West Virginia Department of Mines and appointed Oscar Veazey as the first mine inspector. That year the first Annual Report was prepared, and the following year, Veazey proposed the first comprehensive mine safety laws. However, nothing was enacted.

On January 21, 1886, West Virginia’s first significant mining accident occurred at the Mountain Brook mine in Newburg. The methane gas and dust explosion ignited by an open light killed 39 men and was classified as the first mining “disaster” in the state. This would be the first in a long line of “disasters” in the following years.

In 1887, the Legislature passed the first significant mine safety laws; however, they were not published until 1897.

In the next decade, coal production increased from slightly more than two million tons in 1883 to more than 11 million tons by 1894. That year, the United Mine Works went on strike in West Virginia.

The next disaster occurred in Standard, West Virginia, on November 20, 1894. When coal was blasted using a dangerous method called “shooting from the solid,” meaning that they blasted the coal loose without first undercutting it, eight men lost their lives. Just two years earlier, three men had been killed there in the same manner.

By 1900, coal production had doubled to more than 22 million tons. The boom ushered in a period of great danger. Three months into the 20th century, a miner’s open light ignited methane gas at the Red Ash mine in Fayette County on March 6, 1900. The resulting explosion killed 46 men, many of whom were descendants of slaves, who had been lured from the South by the promise of good jobs.

In the early 1900s, over 18 months, a mine worker’s chance of being crushed, asphyxiated, burned, blasted, drowned, or similarly maimed or killed was more than 100%.

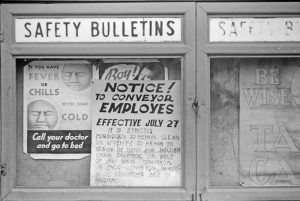

In 1905 the West Virginia Department of Mines was created. Two years later, a Mining Commission was appointed to propose new legislation. These laws were printed in the languages of the miners the same year. Though the laws were to improve and monitor mine safety, disasters would continue to occur.

Part of the problem was recruiting unskilled workers, including immigrants, who had never worked in the mines.

On January 29, 1907, at the Stuart Mine in Fayette County, an explosion was caused when an open light ignited gas. Occurring after disregarding safety rules, the explosion killed 85 men, most of whom were unskilled workers.

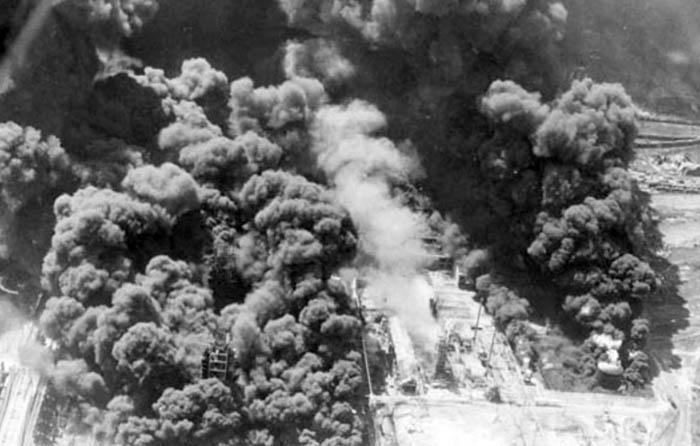

On December 6, 1907, the Fairmont Coal Company’s interconnected Number 6 and 8 mines at Monongah exploded, killing 361 miners, the worst coal mining disaster in U.S. history. People could feel the impacts from the explosions as far as eight miles away. Some people and animals were violently thrown by the force of the event, and many buildings were destroyed. To this day, officials aren’t sure of the cause. Many believe an equipment spark may have ignited dust or gasses in the air. Of those killed, only 74 were classified as “Americans.”

The resulting public outcry brought Congressional action, culminating in creating the U.S. Bureau of Mines in 1910. However, it would not be quick enough.

In that year, the largest number of major mine disaster events occurred in the United States. At this time, the Pullman Company made the first mine rescue railroad cars for the U.S. Bureau of Mines. These cars were former Pullman sleeping cars that were remodeled. The chief work of the car personnel was to investigate the cause of a mine disaster as quickly as possible, assist in the rescue of miners, and give first aid.

In the subsequent years, the cars continuously visited mining centers all over the nation to present demonstrations, lectures, and training. When a mine disaster occurred, the car was moved by a special locomotive or connected to the first train available.

In the first five years, 300 mine accidents, including explosions, fires, and cave-ins, were investigated, 230,000 attended lectures or demonstrations, 34,000 were given training in rescue and first-aid methods, and 11,700 training certificates were issued, increasing continuously from 509 in 1911 to 4,258 in 1915.

The Eccles mine disaster was an explosion of coal-seam methane on April 28, 1914, in Eccles, West Virginia. The explosion took the lives of at least 180 men and boys.

The second worst mine explosion in the state occurred on April 28, 1914, at the New River Collieries Company’s Number 5 mine in Eccles, West Virginia. The gas explosion occurred when a miner decided to eliminate a wall of coal to create a shortcut. However, the controlled explosion cut off ventilation to the mining areas, and an open flame headlamp or lantern ignited the buildup of methane gas, triggering a tremendous explosion. In the tragedy, 183 miners lost their lives, and many of the bodies were trapped in the rubble for four days.

Of the 4,260 miners killed in West Virginia between 1910 and 1920, 579 died in massive explosions and fires.

In the 1920s, new state and federal regulations and insistence for improved safety from the United Mine Workers began to create a safer environment. But disasters still occurred, some of them with significant losses of life. In 1924, the Benwood Mine in Marshall County exploded, killing 119. Three years later, the Federal No. 3 mine at Everettville blew up, killing 111.

On January 10, 1940, 91 died in a methane explosion at the Pond Creek No. 1 mine at Bartley, McDowell County, shattering any illusion that major mine disasters had become a thing of the past.

In the 1950s, ten disasters were added to the terrible total. Notable among these were two explosions at the Pocahontas Fuel Company’s No. 35 mine in Bishop in 1957 and 1958, killing a total of 59 miners.

In the early 1960s, fires, roof falls, and flooding took their toll, but it was nowhere near the numbers in previous years. For instance, a July 23, 1966 explosion at the Siltix Mine near Mount Hope killed seven miners, while 39 escaped.

But just two years later, another explosion occurred on November 20, 1968, when the vast Consolidated No. 9 mine at Farmington exploded, killing 78. Apparent that significant changes still needed to be made, Congress passed the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act in 1969. West Virginia also tightened its rules and regulations. These changes at the state and federal levels finally made a major change in coal mine safety and significantly reduced mine disasters.

On July 22, 1972, at the Blacksville No. 1 mine in Monongalia County, a fire occurred while a continuous mining machine was moved to a new working section. Nine men working deep in the mine perished due to smoke and fumes that carried through the mine’s ventilation system.

Twenty years later, on March 19, 1992, another disaster occurred at the Blacksville No. 1 Mine. By that time, the mine was closed was being sealed. When drainage pipes were welded together and placed into the production shaft, a spark fell into the shaft, igniting methane gas, and four miners were killed.

The last coal mining disaster occurred on April 5, 2010, at the Upper Big Branch Montcoal Eagle Mine in Naoma. The worst mine disaster in 40 years, the explosion killed 29 people.

To date, there have been 119 disasters at mines in West Virginia. Many more miners suffered disabling and lifelong injuries in nonfatal accidents.

Though the mining history in West Virginia is tragic, the state has furnished our nation and the world with the finest bituminous coal found anywhere. Today, the coal industry exhibits a sense of responsibility – social, health, safety, and environmental – that is unmatched anywhere in the world.

There are more people killed in farming accidents in the U.S. today than in coal mining accidents.

West Virginia Coal Mine Disasters:

| Date | Company | Mine | Location | Accident Type | # of Victims |

| January 21, 1886 | Orrel Coal Company | Mountain Brook | Newburg | Gas & Dust Explosion ignited by open light. This was classified as the first mining “disaster” in the state. | 39 |

| November 20, 1894 | Blanch Coal Co. | Blanch | Standard | Explosion | 8 |

| March 06, 1900 | Red Ash Coal Company | Red Ash | Red Ash | Gas Explosion ignited by open light | 46 |

| November 2, 1900 | SO. Coal & Transportation Co. | Berryburg | Berryburg | Powder Explosion | 15 |

| May 15, 1901 | George’s Creek Coal & Iron Co | Chatham | Farmington | Explosion | 10 |

| September 15, 1902 | Algoma Coal and Coke | Algoma No. 7 | Algoma | Explosion | 17 |

| September 22, 1902 | New Central Coal Co. | Stafford | Stafford | Explosion | 6 |

| February 26, 1905 | Grapevine Coal Co. | Grapevine | Wilcoe | Explosion | 7 |

| March 19, 1905 | New River Smokeless Coal Co. | Rush Run/Red Ash | Red Ash | Explosion | 24 |

| April 20, 1905 | Cabin Creek Mining Co. | Cabin Creek | Kayford | Powder Explosion | 6 |

| July 05, 1905 | Tidewater Coal & Coke Co. | Tidewater | Vivian | Explosion | 5 |

| November 04, 1905 | Tidewater Coal & Coke Co. | Tidewater | Vivian | Explosion | 7 |

| December 04, 1905 | Cardiff Coal Co. | Horton | Cabin Creek | Mine Fire | 7 |

| January 04, 1906 | Coaldale Coal & Coke Co. | Coaldale | Coaldale | Explosion | 22 |

| January 18, 1906 | Detroit & Kanawha Coal Co. | Detroit | Paint Creek | Explosion | 18 |

| February 08, 1906 | Stuart Colliery Co. | Parral | Parral | Explosion | 23 |

| March 22, 1906 | Century Coal Co. | Century | Century | Explosion | 23 |

| December 14, 1906 | Pulaski Iron Co | Pulaski | Eckman | Powder Explosion | 6 |

| January 26, 1907 | Lorentz | Lorentz | Penco | Powder Explosion | 12 |

| January 29, 1907 | Stuart Colliery Co. | Stuart | Stuart | Gas Explosion ignited by open light | 85 |

| February 4, 1907 | Davis Coal & Coke Co. | Thomas | Thomas | Explosion | 25 |

| May 01, 1907 | White Oak Fuel Co. | Wipple | Scarbro | Explosion | 46 |

| December 6, 1907 | Fairmont Coal Co. | Monongah 6 & 8 | Monongah | Explosion. This is the worst mining disaster in U.S. history. | 361 |

| January 30, 1908 | New River Valley Coal Co. | Backman | Hawks Nest | Explosion | 9 |

| December 29, 1908 | Pocahontas Colleries Co. | Lick Branch | Switchback | Dust explosion ignited by excessive black powder |

50 |

| January 12, 1909 | Pocahontas Colleries Co. | Lick Branch | Switchback | Overcharged shot ignited coal dust, causing an explosion. | 67 |

| March 31, 1909 | Beury Brothers Coal Co. | Echo | Beury | Dynamite Explosion | 16 |

| December 31, 1910 | Red Jacket Consolidated | Lick Fork | Thacker | Haulage | 10 |

| April 24, 1911 | Davis Coal & Coke Co. | OTT No. 20 | Elk Garden | Explosion | 23 |

| August 01, 1911 | Standard Pocahontas Fuel Co. | Standard | Caples | Explosion | 6 |

| November 18, 1911 | Bottom Creek Coal & Coke Co. | Bottom Creek | Vivian | Explosion | 18 |

| March 26, 1912 | Jed Coal & Coke Co. | Jed | Jed | Gas Explosion ignited by an open light. | 80 |

| July 11, 1912 | Ben Franklin Coal Co. | Panama | Moundsville | Explosion | 8 |

| April 28, 1914 | New River Collieries Co. | Eccles No. 5 & 6 | Eccles | Gas Explosion ignited by an open light. It is the second-worst disaster in the state’s history. | 183 |

| June 30, 1914 | Sycamore Coal Co. | Cinderella | Cinderella | Suffocation | 5 |

| February 6, 1915 | New River Co. | Carlisle | Carlisle | Explosion | 22 |

| March 2, 1915 | New River & Pocahontas Consolidated. Co. | Layland No. 3 | Layland | Gas Explosion ignited by an open light. Survivors included 47 men who were trapped underground for five days. | 112 |

| March 30, 1915 | Hanna Coal Co. | Boomer No. 2 | Boomer | Explosion | 23 |

| March 28, 1916 | King Coal Co. | King No. 28 | Vivian | Explosion | 10 |

| October 19, 1916 | Jamison Coal & Coke Co. | Jamison No. 7 | Barrackville | Explosion | 10 |

| April 18, 1917 | Hutchinson Coal Co. | Lynden | Mason | Explosion | 5 |

| December 15, 1917 | Yukon Pocahontas Coal Co. | Yukon No. 1 | Susanna | Explosion | 18 |

| May 20, 1918 | Mill Creek Cannel Mining Co. | Villa | Charleston | Mine Fire | 13 |

| July 18, 1919 | Houston Collieries Co. | Carswell | Kimball | Explosion | 7 |

| August 6, 1919 | New River & Pocahontas Consolidated | Weirwood | Weirwood | Explosion | 7 |

| May 22, 1920 | Mallory Coal Co. | Mallory No. 3 | Mallory | Roof Fall | 5 |

| September 23, 1922 | Raleigh-Wyoming Coal Co. | Glen Rogers #2 | Glen Rogers | Falling Cage | 5 |

| March 2, 1923 | Weyanoke Coal & Coke Co. | Arista | Arista | Explosion | 10 |

| November 06, 1923 | Raleigh-Wyoming Coal Co. | Glen Rogers | Beckley | Explosion ignited by an arc from an electric drill | 27 |

| March 28, 1924 | Yukon Pocahontas Coal Co. | Yukon No. 2 | Yukon | Gas Explosion ignited by open lights. | 24 |

| April 28, 1924 | Wheeling Steel Corp. | Benwood | Benwood | Gas Explosion ignited by an open light. | 119 |

| March 17, 1925 | Bethlehem Mines Corp. | Barracksville | Barracksville | Explosion | 33 |

| January 14, 1926 | Jamison Coal & Coke Co. | Jamison No. 8 | Farmington | Explosion | 19 |

| March 8, 1926 | Crab Orchard Improvement Co. | Eccles No. 5 | Eccles | Explosion | 19 |

| November 15, 1926 | Glendale Gas Coal Co. | Mound Shaft | Moundsville | Explosion | 5 |

| April 30, 1927 | New England Fuel & Trans. Co. | Federal No. 3 | Everttville | Locomotive ignited a gas explosion | 97 |

| May 13, 1927 | Central Pocahontas Coal Co. | Shannon Br. 3 | Capels | Explosion | 8 |

| April 2, 1928 | Keystone Coal & Coke Co. | Keystone No. 2 | Keystone | Explosion | 8 |

| May 22, 1928 | Yukon Pocahontas Coal Co. | Yukon No. 1 | Yukon | Explosion | 17 |

| June 20, 1928 | National Fuel Co. | No. 1 | National | Explosion | 7 |

| October 22, 1928 | Macalpin Coal Co | McCalpin | McCalpin | Explosion | 6 |

| November 30, 1928 | Princess Pocahontas Coal Corp. | Princess Pocahontas | Roderfield | Explosion | 6 |

| January 26, 1929 | Kingston Pocahontas Coal Co. Inc. | Kingston No. 5 | Kingston | Explosion | 14 |

| January 19, 1930 | Lillybrook Coal Co. | No. 1 | Lillybrook | Explosion | 8 |

| March 26, 1930 | Crown Coal Co. | Yukon | Arnettsville | Explosion | 12 |

| January 6, 1931 | Raleigh-Wyoming Coal Co. | Glen Rogers #2 | Glen Rogers | Explosion | 8 |

| November 3, 1931 | Island Creek Coal Co. | No. 20 | Whitman | Explosion | 5 |

| May 12, 1935 | Bethlehem Mines Corp. | No. 41 | Barracksville | Fire in Shaft | 6 |

| September 2, 1936 | Hutchinson Coal Co. | MacBeth | MacBeth | Explosion | 10 |

| March 11, 1937 | Hutchinson Coal Co. | MacBeth | MacBeth | Explosion | 18 |

| January 10. 1940 | Pond Creek Pocahontas Coal Co. | No. 1 | Bartley | Gas Explosion ignited by an electric arc. | 91 |

| December 17, 1940 | Raleigh Coal & Coke Co. | No. 4 | Raleigh | Explosion | 9 |

| January 22, 1941 | Koppers Coal Co. | Carswell | Carswell | Explosion | 6 |

| May 12, 1942 | Christopher Coal Co. | Christopher #3 | Osage | Gas Explosion ignited by arc in cutting machine control box. |

56 |

| May 18, 1942 | Hitchman Coal & Coke Co. | Hitchman | Benwood | Explosion | 5 |

| July 9, 1942 | Pursglove Coal Mining Co. | Pursglove No. 2 | Pursglove | Explosion | 20 |

| December 15, 1942 | Wyatt Coal Co. | Laing No. 1 | Laing | Runaway Trip | 5 |

| January 8, 1943 | Pursglove Coal Mining Co. | Pursglove No. 15 | Pursglove | Mine Fire Suffocation | 13 |

| November 8, 1943 | American Rolling Mill Co. | Nellis No. 3 | Nellis | Explosion | 11 |

| March 25, 1944 | Kathrine Coal Mining Co. | Kathrine No. 4 | Lumberport | Explosion | 16 |

| January 15, 1946 | New River & Pocahontas Consolidated Coal Co. | Havaco No. 9 | Havaco | Explosion | 15 |

| August 6, 1948 | New River & Pocahontas Consolidated Coal Co. | Berwind No. 11 | Capels | Roof Fall | 6 |

| January 18, 1951 | Burning Springs Collieries Co. | Burning Springs | Kermit | Gas Explosion | 11 |

| October 15, 1951 | Trotter Coal Co. | Bunker | Cassville | Gas Explosion | 110 |

| October 31, 1951 | Truax-Traer Coal Co. | United No. 1 | Wevaco | Dust Explosion | 12 |

| November 13, 1954 | Jamison Coal & Coke Co. | No. 9 | Farmington | Explosion | 16 |

| February 4, 1957 | Pocahontas Fuel Co. | No. 35 | Bishop | Gas Explosion | 37 |

| December 9, 1957 | Raleigh-Wyoming Coal Co. | Glen Rogers No.2 | Glen Rogers | Mountain Bump | 5 |

| December 27, 1957 | Pocahontas Fuel Co. | No. 31 | Amonate | Gas Explosion | 11 |

| February 12, 1958 | Amherst Coal Co. | Lundale | Lundale | Roof Fall | 6 |

| October 27, 1958 | Pocahontas Fuel Co. | No. 35 | Bishop | Gas Explosion | 22 |

| October 28, 1958 | Oglebay Norton Coal Co. | Burton | Craigsville | Gas Explosion | 14 |

| March 8, 1960 | Island Creek Coal Co. | No. 22 | Holden | Mine Fire | 18 |

| November 9, 1962 | Island Creek Coal Co. | No. 28 | Verdunville | Haulage | 3 |

| April 25, 1963 | Clinchfield Coal Co. | Compass No. 2 | Dola | Gas Explosion | 22 |

| September 28, 1964 | Island Creek Coal Co. | No. 6 | Bartley | Gas Explosion | 3 |

| April 30, 1965 | Mountaineer Coal Co. (Division of Consolidation Coal Co.) | Consolidation No. 9 | Farmington | Gas Explosion | 4 |

| May 3, 1965 | Dorothy Coal Co. | No. 1 | Garrison | Roof Fall | 3 |

| October 16, 1965 | Clinchfield Coal Co. | Mars No. 2 | Sardis | Mine Fire | 7 |

| July 23, 1966 | New River Co. | Siltix | Mount Hope | Gas Explosion | 7 |

| September 10, 1966 | Valley Camp Coal | No. 3 | Triadelphia | Haulage | 4 |

| May 06, 1968 | Gauley Coal & Coke Co. | No. 8 | Hominy Falls | Mine Inundation | 4 |

| August 14, 1968 | Amherst Coal Co. | Lundale No. 1 | Logan | Roof Fall | 3 |

| November 20, 1968 | Mountaineer Coal Co. (Division of Consolidation Coal Co.) | No. 9 | Farmington | Explosion | 78 |

| December 12, 1968 | Buffalo Mining Co. | No. 8B | Lyburn | Mine Fire | 3 |

| June 11, 1971 | Eastern Associated Coal Corp. | Federal No. 2 | Fairview | Roof Fall | 3 |

| July 22, 1972 | Consolidation Coal Co. | Blacksville | Blacksville | Mine Fire | 9 |

| December 16, 1972 | Itmann Coal Co. | Itmann No. 3 | Itmann | Gas Explosion | 5 |

| October 02, 1974 | Cowin & Co. (Contractors) | Maple Meadow Mine | Fairdale | Falling Material | 3 |

| October 07, 1974 | Monty Bros. Const. Co. (Contractor) | Bolt Sewell | Bolt | Fall in Shaft | 3 |

| June 05, 1975 | Eastern Associated Coal Corp. | Harris No. 2 | Bald Knob | Rib Fall | 3 |

| November 26, 1975 | Bethlehem Mines Corp. | No. 105 | Century | Roof Fall | 3 |

| November 07, 1980 | Westmorel & Coal Co. | Ferrell | Uneeda | Gas Explosion | 5 |

| December 03, 1981 | Elk River Sewell Coal Co. | Still House No. 1 | Bergoo | Roof Fall | 3 |

| February 06, 1986 | Consolidation Coal Co. | Loveridge No. 22 | Fairview | Coal Storage Entrapment | 5 |

| March 19, 1992 | Consolidation Coal Co. | Blacksville No. 1 | Wana | Explosion In Shaft | 4 |

| January 22, 2003 | Central Cambria Drilling Co. (Contractor) | McCelroy Mine | Graysville | Explosion in Shaft | 3 |

| January 2, 2006 | Anker WV Mining Co., Inc. | Sago Mine | Tallmansville | Explosion & Entrapment | 12 |

| April 5, 2010 | Performance Coal Co. | UBBMC Montcoal Eagle | Naoma | Explosion | 29 |

©Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, November 2021.

Also See: