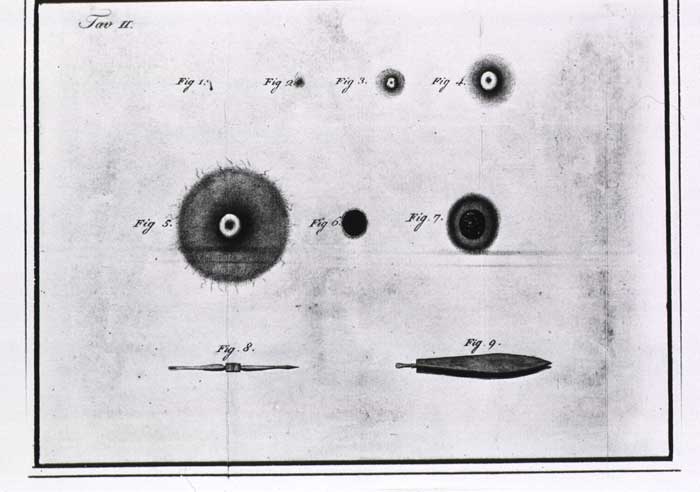

A patient with smallpox is depicted in this 18th-century drawing.

“Our Misfortunes in Canada are enough to melt a Heart of Stone. The Small Pox is ten times more terrible than Britons, Canadians, and Indians together”.

– John Adams in a letter to his wife Abigail, June 26, 1776.

We Americans can thank, in part, smallpox for helping us win our independence.

Smallpox was nothing new in the 1700s. It was among the most widespread and deadliest of diseases, brought to the Americas by the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors, devastating indigenous populations of South and Central America. It was even used as a biological weapon by the British during the French and Indian War to hurt Native Americans who were assisting France.

Europe and Asia had already figured out that those who survived smallpox usually didn’t catch it again, and if they did, it was a lot less severe. This led to the practice of vaccination, a procedure that involved removing an active abscess from an infected person and inserting it through a small incision in someone not infected. The result is that the inoculated person contracts the disease, but usually with only mild symptoms. Europe, Asia, and parts of Africa thus mainly became immune to smallpox; however, it was a little different in the American Colonies because there was never a widespread epidemic, only sporadic outbreaks, and therefore no herd immunity.

In this medical diagram, illustrations 1 through 7 depict smallpox pustules, with 8 & 9 being the medical instruments used for injection.

The practice of vaccination came to the colonies in 1721 when it was introduced in Boston, Massachusetts. Reverend Cotton Mather, a participant in the Salem Witch Trials just a few decades earlier, learned about the inoculation process from his West African slave Onesimus and convinced Boston medical doctor Zabdiel Boylston to start vaccinations in the city. However, inoculation became controversial in Boston as many believed the procedure to be more deadly than naturally contracting smallpox. In addition, clergy argued that smallpox was God’s punishment for sin and shouldn’t be interfered with. It became so contentious that one Boston resident threw a fire bomb at Mather’s home to intimidate the Reverend and Dr. Boylston from continuing the practice.

Battle of Bunker Hill during the American Revolution by John Trumbull

Boylston continued his inoculations and, with time, was able to prove their effectiveness. The city suffered at least four significant outbreaks in the 1700s, including one in 1775. After the Battle of Bunker Hill that June, military movements and actions by the British and Colonists stalled as General Howe and his British troops occupied Boston. Smallpox ran rampant through the city, infecting some of Howe’s troops. General George Washington knew his Continental soldiers were not immune and were more likely in danger of the disease. So even after the stalemate ended in March of 1776, and Howe evacuated the British Army, Washington didn’t allow anyone who had not previously had smallpox to enter the city. It was March 17 before the future first President would permit 1,000 soldiers, all survivors of the disease, to enter Boston.

Smallpox continued to affect military operations during the Revolution, so much so that it ravaged troops who planned to prevent Quebec, Canada, from falling to the Brits in late 1775. Many Continental troops could not fight as they were sick, leading to their defeat in Quebec on December 30. When it was time to re-enlist in 1776, many soldiers refused, deciding to desert the cause rather than face the disease. Others decided to inoculate themselves but did not realize one crucial step, quarantine after. This furthered the spread of the disease to the point that Colonel Benedict Arnold, in February 1776, issued orders that forbade inoculations.

Despite being threatened by the death penalty, soldiers started inoculating themselves secretly, still without quarantine, thus making the spread even worse. Substantial forces were maintained around the city, hoping for a second attempt, but smallpox continued to impede any future offensives. Major General John Thomas took control of the troops that March, with Congress hoping his medical experience could help stop the outbreaks. Thomas, however, was afraid of allowing injections due to the recovery time needed for soldiers who get them. And since he forbade his men from being inoculated and quarantined, he was also left vulnerable. It wasn’t long after his arrival that he contracted Smallpox and died.

In June of 1776, John Adams, in Philidelphia helping establish a nation, wrote to his wife Abigail, “Our misfortunes in Canada are enough to melt a heart of stone. The smallpox is ten times more terrible than Britons, Canadians, and Indians together. This was the cause of our precipitate retreat from Quebeck [sic]; this is the cause of our disgraces at the Cedars.” It was apparent the disease was mightier than the British and Continental Army and was the cause of the Americans’ defeat in Canada.

America’s First Medical Mandate

George Washington & Lafayette visited sick troops at Valley Forge in 1777 by P. Haas.

General Washington was well aware of what happened in Canada and feared that not taking any steps to prevent the disease’s spread amongst the troops would lead to disaster. Washington wrote a letter to Dr. William Shippen Jr., Medical Director of the Continental Army, in February 1777, which said in part, “Finding the Smallpox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running through the whole of our Army, I have determined that the troops shall be inoculated. This Expedient may be attended with some inconveniences and some disadvantages, but yet I trust in its consequences will have the most happy effects.”

With that order, General Washington enacted the first medical mandate in American History. Though firm in his resolve, some called it a mistake and even brought doubt to himself. He stood fast to the order and instructed Congress that all troops must be inoculated. To achieve this, all new recruits entering Philadelphia were inoculated, and divisions of the army were inoculated in five-day intervals, using private homes and churches as quarantine centers. And this was all done in secret, for if the British knew when the American troops were weak, they would surely attack.

Washington wanted this done immediately to have the troops needed in the summer of 1777. But he had resistance from a few of his Generals and some Colony governors who prohibited the inoculations. Virginia Governor Patrick Henry wrote to Washington saying he couldn’t supply troops to the General’s campaign due to a smallpox outbreak. In response, Washington wrote him back in April of 1777:

“The Apologies you offer for your deficiency of Troops are not without some Weight. I am induced to believe that the apprehensions of the Smallpox & its calamitous consequences have greatly retarded the Enlistments; but may not those Objections be easily done away by introducing Innoculation into the State—Or shall we adhere to a regulation preventing it, reprobated at this time not only by the consent & usage of the greater part of the civilized World but by our Interest & own experience of its Utility? You will pardon my Observations upon the Smallpox because I know it is more destructive to an Army in the Natural way than the Enemy’s Sword and because I shudder whenever I reflect upon the difficulties of keeping it out and that in the vicissitudes of War, the Scene may be transferred to some Southern State should it not be the case their Quota of Men must come to the Feild.”

Gaining support for his medical mandate was slow, but by late 1777 the procedure had been established in the Continental Army. With the smallpox threat diminished, army enlistments surged. Many historians credit the medical mandate with the American victory in the Revolutionary War and the creation of the United States.

It wouldn’t be until 1796 that Edward Jenner created the Smallpox Vaccine.

©Dave Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Disease & Death Comes to the Plains Indians

George Washington – Father of our Country

Sources:

Smallpox, Inoculation, and the Revolutionary War – National Park Service

Adams Papers – National Archives

Washington Papers – National Archives