“There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal rights and privileges in the United States.”

— Victor Hugo Green, 1936

The Negro Motorist Green Book was a guidebook published annually for African-Americans traveling across the country.

The book was the idea of an African American mailman in New York City named Victor Hugo Green, who began to publish the book in 1936. This was during the era of Jim Crow laws when open and often legally prescribed discrimination was widespread against African Americans, especially in the South.

By this time, black people were buying automobiles and began to travel just like everyone else. However, state laws in the South required separate facilities for African Americans, which included motels and restaurants. Even in the northern states, many businesses excluded them. In addition to finding services, simple trips made by black people were often fraught with potential dangers. In many places, those who could afford an automobile and could travel were seen as “uppity” or “too prosperous,” which could lead to no service, harassment, and abuse. They were sometimes subjected to racial profiling by law enforcement, and in some communities, referred to as “Sundown Towns,” no one of color was allowed in the town after sunset.

In the 1930s, Green began compiling information on stores, motels, and gas stations in the New York City area that welcomed black customers. In 1936, Hugo Green published the first edition of his book that listed places that were safe for blacks to stop, buy gas, eat, and spend the night. Because, in some places, there were no lodging facilities that would accept African-American guests, Green listed “tourist homes,” where black families could rent a room.

The guide, often called the “Bible of Black Travel,” was so popular that he immediately expanded the book’s coverage to include other U.S. destinations. He established a publishing office in Harlem, New York, to support this effort. Publishing 15,000 copies annually, he marketed them to both black and white-owned businesses. One of the biggest was Esso gas stations, which was one of the few companies that would sell their franchises to African Americans. Esso then sold the books to traveling customers.

In 1947, he established a travel agency that booked reservations at black-owned establishments. Two years later, the guide had grown to include destinations in Bermuda and Mexico.

“The Negro traveler’s inconveniences are many and they are increasing because today so many more are traveling, individually and in groups.”

— Wendell P. Alston, The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1949

When Hugo Green died in 1960, his wife Alma became the book’s editor and continued publishing until 1966.

In the meantime, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, ending racial segregation in public facilities.

Though numerous highways and cities were listed in the book, one popular road during this era was Route 66, which made its way from Chicago, Illinois, to the Southwest and Los Angeles, California.

This highway, also referred to as “America’s Mother Road”, is often romanticized, with many seeing it as a link to our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents, and others feeling the sense of freedom that the road provided those earlier travelers. And for folks like us, Route 66 is, but yet, the next adventure beyond the Old West days of the Santa Fe Trail, another “super-highway” to bring Americans through small-town U.S.A. on their way West.

In all that nostalgia, though, we shouldn’t forget that the experience of the Mother Road wasn’t the same for Americans of Color. In fact, as a noted author, photographer, and cultural critic Candacy Taylor wrote,

“Being black and traveling away from home during the Jim Crow era of racial segregation in the U.S. was potentially life-threatening.”

Taylor teamed up with the National Park Service for a special project that shines a light on Victor Green’s publication to keep black travelers safe.

Victor H. Green began his publication about ten years after Route 66 was officially designated.

Noted author and historian Michael Wallis, who has played a big part in the resurging interest in Route 66, wrote in an essay, stating:

“As a boy, I saw the “No Colored” signs at gas stations on my Route 66 just as I did on the roads of the Deep South.” Wallis continues: “Black families traveling America’s byways packed their own food and often slept in their vehicles. They didn’t get their kicks on Route 66 – or at least the kind of kicks I was getting as a youngster or a few years later as a hitchhiking Marine.” Wallis says that the Green Book probably saved a good many lives and that “the old road has plenty of scar tissue, much to be ashamed of and much to brag about, as well as a bright future. It is an unfinished story – a work in progress.”

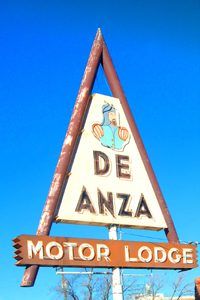

Part of that “work in progress” is documenting the darker side of America’s Mother Road, and learning the history from more than just the nostalgic memories of those who didn’t have to worry about where they were going to eat, sleep or even get gas. After all, Route 66 reflected the nation at the time, its glory and horror on display the same. That’s why Candacy Taylor’s work with the National Park Service’s Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program is so important. Taylor has traveled the Route, documenting what is left of those brave businesses who were listed in the Green Book. She writes that of the 250 Green Book sites listed in the 1960s along Route 66, over half are gone. Motels like the DeAnza Motor Lodge in Albuquerque, Fred Harvey Restaurants and Hotels, and others played a key role for thousands of travelers who had to carefully plan their travel to avoid the pitfalls of Jim Crow laws and racism.

The Park Service’s Route 66 Green Book Project is designed to help shed light on the important stories of racial discrimination for Blacks and other travelers of color. And to lead to the preservation of remaining business buildings in the book to promote commemoration and gain insights and understanding of those who relied on it to experience Route 66.

For more information on the project, see the National Park Service website HERE, which includes a link to a complete listing of properties along Route 66 that were included in the Green Book.

It’s worth noting as well that Missouri State University also teamed with the National Park Service on the project and is producing a series of video interviews discussing minority experiences and memories of Historic Route 66 in Green County Missouri and Springfield, Missouri, the birthplace of Route 66.

©Dave Alexander, Kathy Alexander, updated January 2024.

The Negro Motorist Green Book and Route 66, produced by Candacy Taylor in partnership with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program.

African American History in the United States

Sources:

Huffington Post

Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program

Taylor, Candacy, Route 66’s Legacy of Racial Segregation, The Guardian, February 2015

Wallis, Michael, The Other Mother Road, This Land Press, March 2014

Wikipedia