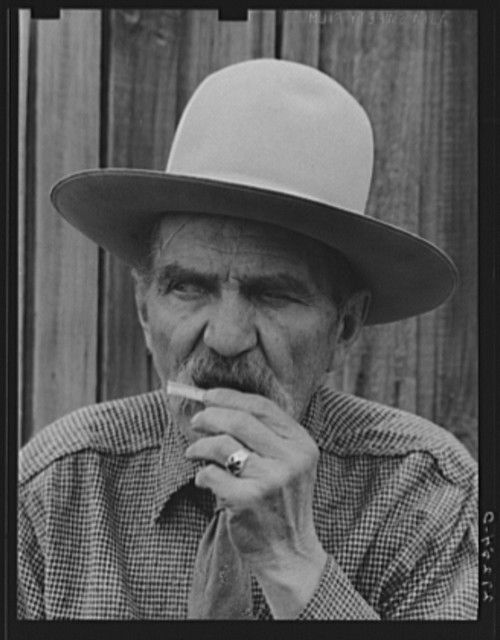

Frank Latta, one time Montana lawman, in the autumn of his years. He had one bad eye that was damaged when he was chopping wood. That star sapphire he’s wearing now belongs to my (R.Chapman) Uncle Jack. (1939 Photo by Arthur Rothstein, Courtesy of the National Library of Congress)

A Tale of My Great Grandfather in Montana: How Skill Caught a Criminal and Luck Saved the Lawman’s Life – By Robin Chapman, 2010

I never knew my great-grandfather Frank Latta of Bozeman, Montana. But I have come across a new picture of him in sorting through my mother’s things after her recent death. The picture explains a key element of a story that is often told about the old lawman and his capture of a notorious railroad extortionist in 1903.

The criminal was Isaac “Ike” Gravelle. He was an ex-con and a generally bad guy who sent a series of anonymous letters to the Northern Pacific Railroad, threatening to blow up bridges and trains if he was not paid $25,000.

The railroads in those days were powerful and wealthy, and they didn’t pay these threats much mind. That is until he blew up a railroad bridge over the Yellowstone River, blew an engine off the tracks near Birdseye, Montana, and derailed a train west of Elliston.

He had stolen the dynamite for his operation from a Helena hardware store, and one day a ranch hand from an outfit called Antelope Springs was riding along the tracks near the Missouri River when he surprised a guy sleeping in a haystack. When the loner lit out on his horse, he left a rucksack of dynamite behind him and a spur. The spur was identified by a Helena blacksmith as one he’d made for Ike Gravelle, and now he’d been identified, the hunt was on.

In October 1903, he was spotted 23 miles west of Helena. Three lawmen began to track him: Maj. James Keown, another man called Bert Reynolds, and my great-grandfather Frank Latta. They used a pack of bloodhounds, and they used Frank Latta’s famous skills at tracking. Into the night, they tracked Ike Gravelle through McDonald Pass, Mullan Tunnel, and Priest Pass. Finally, according to editor Frank Walker in Speaking Ill of the Dead: Jerks in Montana History:

” …they ran him to ground at his old hog ranch near Priest Pass and, without firing a shot, captured their prey. In most dramatic fashion, the Northern Pacific lawmen trailed Ike down into Helena with his hands bound behind his back. The triumphant captors had telephoned ahead, and hundreds of townspeople lined Helena Avenue to gawk at the blackmailer who had terrorized the entire state of Montana for three long months.”

Gravelle, looking sinister. Courtesy Montana Historical Society

On New Year’s Eve 1903, Gravelle was convicted. Before he was led away to the jail, he asked to use the men’s room, and there, in a stall, a person or persons unknown had planted a revolver for Ike. He used it to escape, shooting and killing deputy Anton Korizek in the struggle. He had told friends what he really wanted to do was to kill Frank Latta, that son-of-a-gun who had tracked him down.

The jury had only been out four hours before returning its verdict that day, and the story goes that my great-grandfather, Frank Latta, was just returning to the courthouse when the escape took place. He’d been buying himself a new Stetson with some of the reward money he won for Ike’s capture, and he was walking up onto the courthouse steps just as Gravelle brushed past him and ran on down the street.

The escape was Gravelle’s last desperate act. As he ran, he shot and mortally wounded another man–one of the witnesses at his trial who had pulled out his own revolver and given chase. But, it wasn’t long before lawmen had Gravelle cornered in the stairway leading down to the coal room of the brand new Montana governor’s mansion. Ike turned the gun on himself and ended his life.

“Why didn’t he shoot you,” people asked Frank Latta when the ruckus had died down. “He was a killer with nothing to lose. He said he’d kill you too.”

“Well,” said Frank. “I had on my new Stetson. I guess he just didn’t recognize me in that brand new hat.”

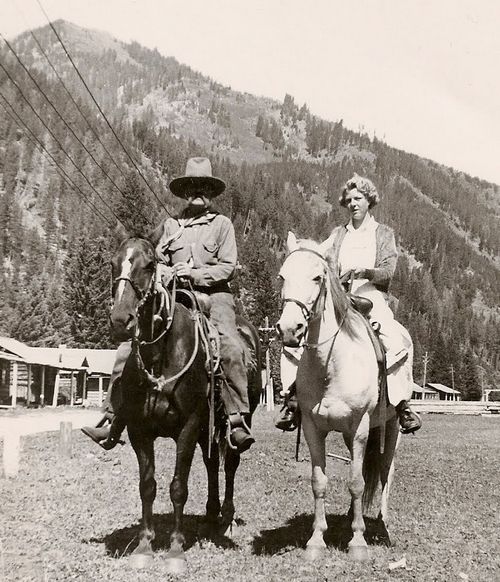

Below is the picture I found among my mother’s things, a photo taken thirty years after the famous Gravelle case. That’s my mother with my great-grandfather, Montanan Frank Latta.

Faye Latta, my (R.Chapman) mother, with her grandfather, Frank Latta, whose hat saved his life one day in 1903. Photo 1936

I don’t know what hat he had on the day Ike Gravelle escaped, but if it was anything like the one he’s wearing in this photo, with a brim just the right size to block the Montana sun and put a cowboy’s features in total darkness, it is easy to understand why the famous criminal might have failed, on that fateful day, to identify the man who tracked him down.

The mustache would have been a dead giveaway. It must not have been quite so impressive in 1903.

© Copyright Robin Chapman News, 2012. Updated November 2022.

About the Author: Robin Chapman is the maternal great-granddaughter of the legendary lawman Frank Latta, and the granddaughter of Harry Latta, who served as a Sheriff’s Deputy in Spokane, Washington. She’s a long-time television journalist, reporter, and writer and lives in the family home in California.

Also See: