Dyea, Alaska, was a wild boomtown during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-1898, but today it is a complete ghost town.

It is unknown when the village of Dyea was established, but in the decades before the gold rush, Dyea was a seasonal fishing camp and staging area for trade trips between the coast and the interior. Dayéi is the Tlingit Indian word that means “to pack.”

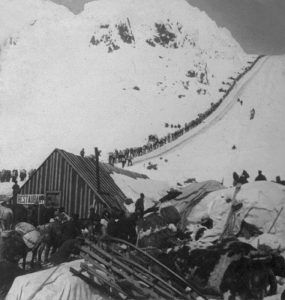

The Chilkat Tlingit Indians from Klukwan, Alaska, had long used this area and Chilkoot Pass to trade with the interior First Nations people. It was their main trade route to the interior, and they did not permit others to use the pass. They provided goods from the interior to Russian, Boston, and Hudson’s Bay trading companies. Their control reached beyond Dyea, even burning Fort Selkirk in the Yukon in 1852 when the Hudson’s Bay Company attempted to trade directly with the interior First Nations people.

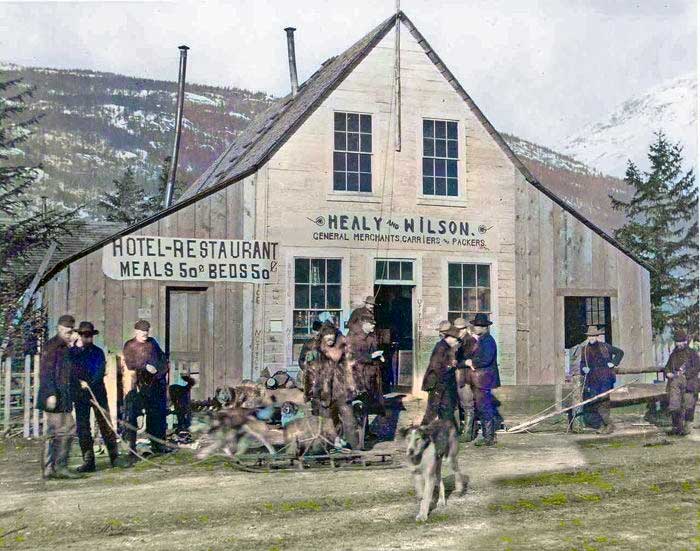

Healy-Wilson Trading Post, Dyea, Alaska, 1890s. Touch of color by LOA.

In 1879, U.S. Navy Commander L.A. Beardsley agreed with the Chilkat Tlingit people that miners would be permitted to reach the Yukon via the passes but would not interfere with their regular trade. Tlingit guides accompanied the first party over the pass in May 1880 and transported the miners’ gear for a fee. This trip set the foundation for the Tlingit packing business, which thrived during the gold rush.

Dyea’s status changed with the establishment of the Healy & Wilson trading post in the mid‑1880s. Before coming to Alaska, John J. Healy had been a hunter, trapper, soldier, prospector, whiskey trader, editor, guide, Indian scout, and sheriff. He was living in Montana Territory when he heard about the early, pre-Klondike Yukon gold strikes and soon headed north. Edgar Wilson was Healy’s partner and brother-in-law, but not much is known of him. Wilson may have arrived in Dyea a season or two before Healey’s appearance, laying the groundwork for the trading post. The Healy & Wilson trading post consisted of a wood‑frame building as a combination store and residence, a barn, and a nearby garden. The post was an important supply and information point for prospectors heading into the Yukon basin before the Klondike Gold Rush. Alaska Natives and First Nation peoples gathered there, particularly in the spring, to help prospectors pack their outfits over the Chilkoot Pass. The Tlingit Village was located just upriver.

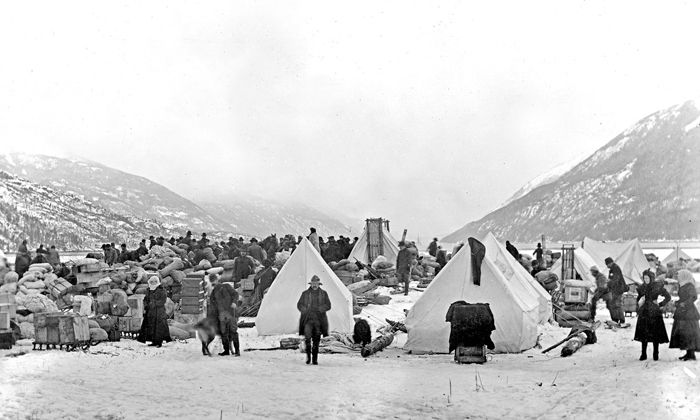

Dyea’s real boom began in the fall of 1897 after word about the wealth of the Klondike strike made newspaper headlines in mid‑July 1897. For months, jammed boatloads of prospectors disembarked in Dyea and streamed north over the Chilkoot Pass. Few people remained in the area very long, and by September 1897, Dyea was nothing more than the Healy & Wilson trading post, a few saloons, the Tlingit encampment, and a motley assemblage of tents however, that changed in October when speculators mapped out a townsite.

Dyea’s most significant growth began when the Yukon River system started to freeze, and the winter storms slowed traffic on the Chilkoot Trail. The town had 1,200 people by mid-December, many of which lived in tents, but streets had been laid out, and carpenters were busy building structures. In January 1898, the Dyea Trail newspaper began publication, boasting that “the world can now be assured the finest system of Wharves and Warehouses in all Alaska will be constructed here at the mouth of the Chilkoot Pass, the only route to the greatest goldfields known to history.”

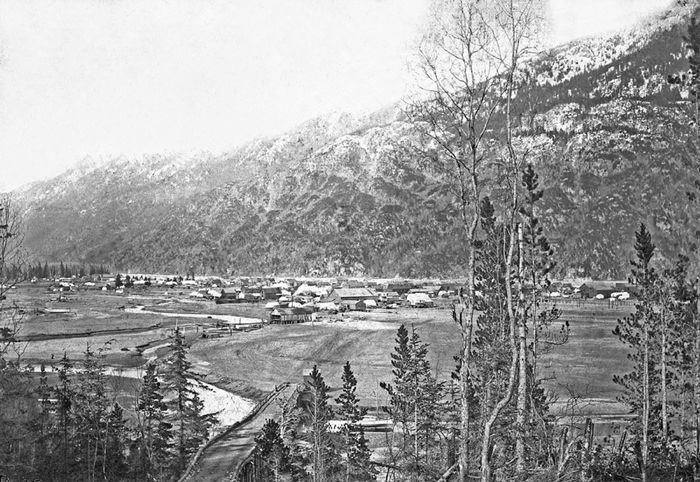

In 1898, Dyea reached its height of prosperity, boasting over 150 businesses, including restaurants, hotels, supply houses, and saloons. Some of the town’s new buildings were large, including the Olympic Hotel, a three-story, 75-by-100-foot structure billed as “the largest in Alaska.” The boomtown also boasted two breweries, attorneys, bankers, freighting companies, photographers, steamships, and real estate agents.

Another newspaper called the Dyea Press also started, and the town had two companies, one that ran its line up the Chilkoot Trail to Bennett and the other that ran its line to Skagway. To care for the health of its citizens, the community sported drug stores, doctors, a dentist, two hospitals, and three undertakers. There were also two wharves, many warehouses and freight sorting areas, and a sawmill. The town also had one church of the Methodist-Episcopalian denomination. Although the town never established a “formal government,” it had a Chamber of Commerce, a volunteer fire department, and a school that began in May 1898. The downtown area was about five blocks wide and eight blocks long. Its population peaked this year with 3,500 residents.

Immediately north of the downtown area was Camp Dyea, established by U.S. Army troops in March 1898. When the troops arrived in Dyea, they paid little attention to the site where they established their camp, and their tents were scattered across a large field south of the Healy & Wilson trading post. But drainage problems existed at the site; the nearest potable water was over a half‑mile away, and the camp was not directly accessible by water. Therefore, the troops sought another location, and in October 1898, they moved three miles south along the west side of Taiya Inlet. There, the army secured the Dyea‑Klondike Transportation Company dock and buildings to use.

North of the downtown area, River Street wound along the banks of the Taiya River up to the Healy & Wilson store, the mid-part of town. Beyond that, the traveler on River Street encountered the Tlingit Village and other boomtown stores scattered along the road. Near the northern end of town, approximately two miles from the high tide line, another business center catered to southbound traffic.

Dyea initially competed on reasonably even terms with Skagway, located about nine miles to the east. But, in the spring of 1898, Dyea began to lose its competitive edge. On April 3, 1898, there was a massive snow slide, known as the “Palm Sunday Avalanche,” on the Chilkoot Trail. Occurring north of Sheep Camp, the avalanche killed over 70 people and brought worldwide negative publicity, steering many prospectors away from Dyea. The opening of the Yukon River also brought a mass exodus from the town as the stampeders left for Dawson City.

The final death knell to Dyea was the construction of the White Pass & Yukon Route railroad, which began in Skagway in May 1898 and funneled most new stampeders to Skagway. Freight destined for the tramways of the Chilkoot Railroad & Transport Company continued to pour through Dyea, but few passengers filed into town. By then, the gold rush was already declining, and only one town was needed to service traffic to the interior.

Beginning with the fall of 1898, Dyea began to fade away, and that winter, the onslaught of winter snows slowed and then halted the tramway operations on the Chilkoot Trail. By the spring of 1899, portions of the Long Wharf were no longer usable, and in July, a forest fire burned the U.S. Army camp at the Dyea-Klondike Transportation Company. The troops then permanently moved to Skagway.

In early 1900 most of the tramway apparatus was removed from the Chilkoot Trail, which ceased to be a transportation corridor after hundreds of years. Without a trail leading north, Dyea’s reason for existence vanished. By March 1900, only about 250 people remained in the town, and its school closed in June 1900. By the spring of 1901, it had dropped to just 71 people.

At that point, the valley began to show opportunities as a farming area, and a few operators raised vegetables intermittently for the next 40 years. Others sold their land to Harriet Pullen, the well‑known Skagway hotel owner.

The post office closed in June 1902, and by 1903 less than a half‑dozen people occupied the remains of the old townsite. Meanwhile, the remains of the old townsite slowly disappeared. A few of the owners dismantled their buildings and took them elsewhere. Emil Klatt, who farmed in the valley for years after the gold rush, burned or disassembled many old buildings gaining some money by selling off lumber and hardware and expanding his farm. Fires destroyed some buildings, including the landmark Healy & Wilson trading post in 1921, and vandalism ruined a few others. Time and the elements wore down many of the other old buildings, and a shift in the path of the Taiya River undermined over half of the downtown area in the 1920s and 1930s. Some of the buildings from the town remained until after World War II but more floods in the mid‑1940s and early 1950s destroyed most structures that were left standing.

In February 1978, the National Park Service bought much of the old townsite of Dyea, recognized as a National Historic Landmark. Today there is scant evidence that the town ever existed, and it is an archeological site.

One thing that remains at Dyea is the Slide Cemetery, which are the graves of many of the people killed in the Palm Sunday Avalanche of 1898. It is the only cemetery within the bounds of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

The townsite of Dyea and the Chilkoot Trail are part of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps Across America

Seattle & the Klondike Gold Rush

Skagway, Alaska – Jumping Off to the Klondike

Sources:

Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park

National Park Service