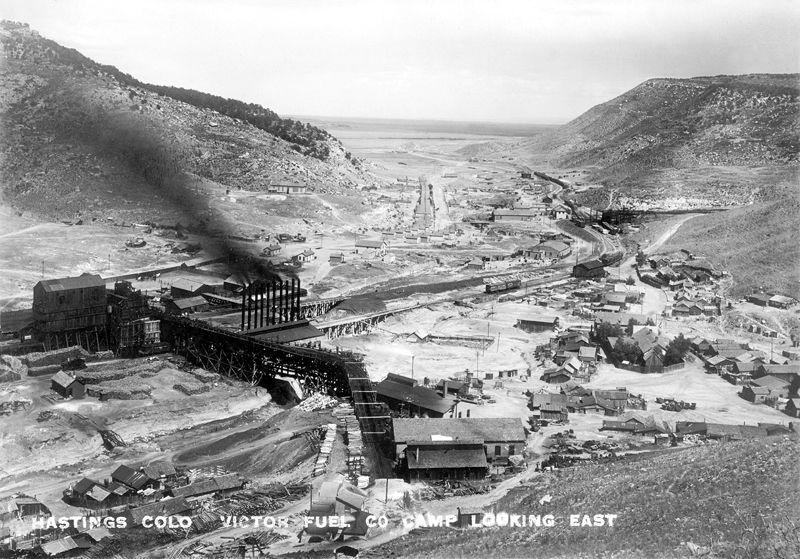

Hastings, Colorado, started as a railroad station in 1889 and quickly developed into a coal mining camp, founded by its owner, the Victor American Fuel Company, Colorado’s oldest mining company. However, mining had occurred at the site since the 1870s.

The Canon de Agua Railroad Company, a predecessor of the Union Pacific, Denver, and Gulf Railway Company, constructed a railroad here between 1888 and 1889. The tracks connected with the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad at Barnes, three miles east of the mine. The Victor American Fuel Company later bought out the railway line and became part of the Colorado & Southeastern Railroad.

Victor Station was established in 1889, including a post office named Hastings. The town’s corporate limits were filed in May 1892, and most of the camp’s buildings were constructed by the following year. By the end of 1899, the Denver Times described Hastings as:

“The seat of operations of the Victor Fuel Company. The camp has a population of nearly 1,000, is engaged in mining, and supplies 100 [coke] ovens with some of the best coking coal in the district… The Victor Fuel Company furnishes supplies to all the railroads, smelters, mills, and reduction plants …The coke output is partly distributed through the state; the balance finds its way into Mexico, New Mexico, and Arizona and is used in the copper, gold, silver, and lead smelters.”

Coke is coal baked in ovens to remove impurities and water to burn at the high temperatures required for steelmaking and smelting.

In 1900, the settlement boasted a population of 1,174 people. In 1903, the railroad line was extended from Hastings to the mining camp of Delagua, which the Victor American Fuel Company also owned. By 1910, Hastings had a company store, a meat market, a saloon, a church, and an excellent public school.

By 1915, the town boasted 1,200 people. At that time, the company operated 190 coke ovens at Hastings, producing about 300 tons of coke and 2,300 tons of coal per day drawn from the Hastings and Delagua mines.

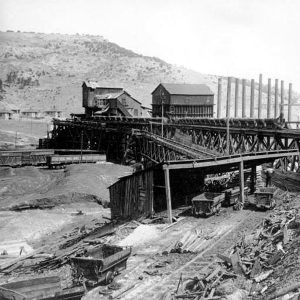

A 1917 report by a U.S. Bureau of Mines inspector described Hastings:

“Surface buildings, in general, are substantially constructed, many of the essential brick structures. A coal washery is located at the end of the tipple. From this washery, coal is conveyed to beehive coke ovens a few hundred feet distant by electric larry cars, and refuse is conveyed by an aerial tram to a large dump about one-quarter mile distant. The dwelling houses, some built of brick but generally of frame construction, are located in a comparatively narrow valley between the ledges forming the coal outcrop.”

On June 18, 1912, the Hastings Mine suffered an explosion that killed 12 miners, including the fire boss, and seriously injured another. The accident occurred on a new slope of the mine but didn’t damage the main operations. The explosion occurred at about 10:00 p.m. The first warning of the disaster came when a night watchman saw smoke issuing from the new slope’s mouth shortly before midnight. After it was discovered, mine superintendent James Cameron and David Reese, head of the company’s rescue service, began directing a large rescuers force. The rescuers were able to save one Greek miner, who was severely burned. The only means of exit had caved in, and the other miners suffocated. Investigators believed the explosion was caused by a “windy shot” due to improperly placed charges or using the wrong kind or quantity of explosives, which expend their force on the mine air and sometimes ignite a gas mixture, coal dust, or both.

On April 6, 1917, the U.S. Congress declared war against Germany, beginning America’s involvement in World War I. Just a few weeks later, on April 22, many of the Hasting miners attended the commemoration of the third anniversary of the nearby Ludlow Massacre, which had occurred three years earlier in 1914. The Victor-American Company, one of Colorado’s three largest coal mining companies, was among the principal players in the Ludlow strike.

On that day, the United Mine Workers of America, which had bought the land where the Ludlow Massacre had occurred, dedicated it to those who died during the Colorado Coalfield War. The ceremony attracted thousands of miners and their families, who paraded to Ludlow: “Every man and woman wore a red bandanna, the strikers’ emblem. They waved small American flags and carried the battle-scarred flag of Ludlow triumphantly at the head of the march.” Speeches were made by union leaders commemorating the site and encouraging patriotism and the miners’ support of “their adopted colors” during the war effort. An impromptu baseball game and races added to the amusement.

But things had improved for some of the area miners. Just a month before, at the end of March 1917, the Victor-American Fuel Company, owner of the Hastings mine and previously an ardent opponent of union demands, signed a three-year operating agreement with the United Mine Workers of America.

Just five days after the Ludlow Massacre ceremony, another explosion occurred at Hastings, which was much more severe than the one in 1912. On the morning of April 27, 1917, 122 men went into the Hastings No. 2 coal mine to work. At about 6:30 a.m., a fire boss inspected the mine to ensure it was clear of any methane gas or other hazards. After the mine was cleared, work began as usual, and the miners began hauling coal to the surface utilizing wooden cars and a single cable. The miners were accompanied by Victor-American safety inspector David Reese, who was well-known in the mining community and had directed the rescue attempt during the 1912 explosion.

“Into the dismal pit, he goes, By the light of the lamp that faintly shows Where the dead lie dead in mournful rows…”

— Damon Runyon’s poem, The One-Chance Men

Italian Frank Millatto was riding with the coal cars to the surface that morning, in and out of the mine. He began his third descent into the mine just after 9:00 a.m. that morning, and after he reached about 2,000 feet, he stopped. Though he had neither heard nor felt anything unusual, he climbed out of the car and began investigating the situation when he saw smoke rising toward him. He quickly returned to the surface and gave the alarm. He was the only miner on duty that day to survive.

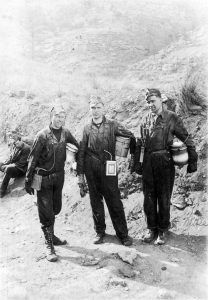

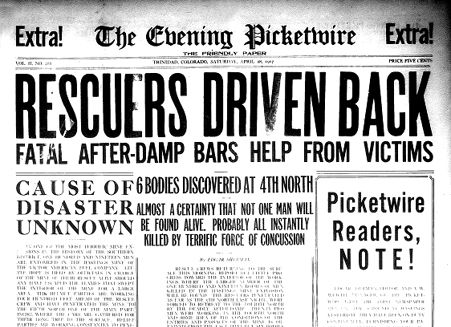

Superintendent Cameron, the night fire boss, quickly formed a rescue party, and rescuers had reached 1,200 feet into the mine before being driven out by smoke at 2:30 p.m. Volunteers arrived from the nearby Delagua and Berwind mines throughout the day. It did not take long to determine that the explosion had caused tons of wreckage, timbers were blown out, boulders had fallen, and tunnels were blocked. Rescuers were further hampered by lack of air, gaseous fumes, and the weight of materials that had to be carried on their backs for up to a mile to make repairs.

The Rocky Mountain News reported: “Virtually every camp in Las Animas and Huerfano Counties [was] represented in the crews of volunteer first-aid men and helmet men.”

“I won’t say we found three men, but we did parts of them.” – Rescuer A. A. Uffman told a reporter.

Some of the men in the mines died from gas fumes, some were crushed, and others were burned beyond recognition.

In the meantime, groups of weeping women and children crowded around the mine entrance and waited.

It soon became apparent that no one had survived, and the operation changed from rescue to recovery. The work of repair and recovery was painfully slow and laborious. Only 19 bodies had been recovered by May 1, but 101 had been recovered by the middle of the month. Some were too badly damaged to be recognized and could only be identified by the brass identification disks they carried. Mine inspector David Reese was found on May 10. Around his body were found the parts of his Wolf key-lock safety lamp that had not been blown apart but had been taken apart. No other body lay within a hundred feet of Reese’s

“The gloom of the catastrophe falls on all.”

– The Denver Post.

Hastings, Colorado Mine Explosion Newspaper Headlines

The Hastings explosion was the worst mining accident in Colorado’s history. It left 64 widows and 149 fatherless children. Of the miners, 35 were Greek, 33 were Austrian, 27 were American, 14 were Italian, 13 were Mexican, three Poles, two Welshmen, a Spaniard, and a Serbian.

Following the vigils came the funerals, sometimes as many as ten or more a day.

Investigators of the explosion were shocked when they found that the explosion had been caused by none other than the Mine Inspector, David Reese. His body was in good condition compared to others when it was found, and the glass in his lamp was not even cracked. Experts testified that “the explosion went both ways from where we found the body. . . . The explosion started with the lamp.”

Although no match was found at the explosion site, Reese had 22 of them on his person. Standard procedures were to search miners for matches before they entered the mine, but Reese wasn’t searched because of his position. After deliberating for 90 minutes, the six miners who constituted the coroner’s jury found that “the cause of the explosion was the opening of a Safety lamp by some person; the evidence shows that the lamp was found near the body of the deceased, David Reese.”

Mining officials were flabbergasted about why the highly regarded 34-year-old Reese, a mine inspector and safety educator, could have made such a fatal mistake.

When a juror asked why Reese would take the lamp apart and try to light it, Victor-American’s district superintendent, D. J. Griffith, replied: “That is something that I can’t make out. What made him to do such a thing? Of course, we thought the lamp was safe in his hands; he was a good, careful man and practical.”

Having had much success in recent mine safety, perhaps an overconfident Reese had dropped his guard. The question, however, will never be answered.

Crews continued to recover bodies for the rest of the year.

Beyond the heartbreak of their suffering, the miners’ survivors constituted the first significant test of the state’s new workers’ compensation law. In May 1917, the State Industrial Commission ruled that the accident required $147,650 in compensation. Dependents of U.S. citizens received $2,500, the equivalent of up to three years’ salary, while non-citizens received $800. Deceased miners without dependents were awarded a burial expense of $75.

In September 1919, James Dalrymple, Colorado State Mine Inspector, ordered the prohibition of key-locked safety lamps in Colorado’s underground coal mines. Afterward, only safety lamps that an igniter could light without taking the lamp apart could be used.

But, hard times for Hastings were not yet over. The final casualty of the Hastings mine explosion was the Hastings mine and the town itself. By November 1917, seven months after the explosion, the mine was only partially worked, and production had dropped dramatically. The company spent almost $128,000 in clearing up and reopening the mine but produced just 74,000 tons in 1917, and it never fully recovered. The Hastings mine had averaged 169,000 tons per year from 1913 through 1916, with peak production of 218,000 tons in 1916.

In 1920, a new development called Hastings No. 5 extracted 73,000 tons, but oil production began to lessen the amount of coal used by the railroads. By 1923, only 7,049 tons were extracted from the mine. The mine was then closed, and the portal was sealed with concrete.

By 1925, a Las Animas County business directory reported that Hasting still had a population of a thousand, including 75 miners. By 1929, the town’s population had dropped to just 300, including four Victor-American employees – an electrician, a mine surveyor, a tippleman, and a watchman. By 1939, the formerly busy mining camp had become a ghost town and in 1948, a business directory listed only one inhabitant.

The final cleanup of the site was completed in 1952, and the railroad tracks were removed. In February 1963, the Denver Post reported on Hastings: “A long row of dilapidated coke ovens and the foundations of a few old buildings are all that remain at the disaster site. Not even a wooden sign marks the location on the dusty road.”

Only a few buildings, concrete foundations, and a row of deteriorating coke ovens remain today. A granite monument to the 121 men who died in the 1917 explosion marks the site.

The old townsite is located about 16 miles northwest of Trinidad, Colorado. Take I-25 North to Exit 27, and travel west on County Road 44 about three miles. Visitors will pass the Ludlow Memorial on the north side of the road and Ludlow’s ghost town on the south before reaching the Hastings townsite.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Also See:

Ludlow and the Colorado Coalfield War

Sources:

Colorado Heritage

Denver Post

Find a Grave

Sherard, Gerald E.; Mining Accidents United States, Canada, Australia & New Zealand