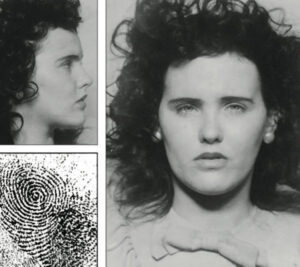

Elizabeth Short, known posthumously as the Black Dahlia was found murdered in the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, on January 15, 1947. Her case became highly publicized owing to the gruesome nature of the crime, which included the mutilation of her corpse, which was bisected at the waist and drained of blood.

Elizabeth Short was born on July 29, 1924, in the Hyde Park section of Boston, Massachusetts, to Cleo Alvin and Phoebe May Sawyer Short. She was the third of five daughters. Her father was a United States Navy sailor, and her mother was a housewife. The Short family briefly relocated to Portland, Maine, in 1927 before settling in Medford, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, that same year. Short’s father built miniature golf courses until he lost most of his savings in the 1929 stock market crash. In 1930, his car was found abandoned on the Charlestown Bridge, and it was assumed that he had jumped into the Charles River.

Believing her husband to be deceased, Phoebe Short began working as a bookkeeper. Troubled by bronchitis and severe asthma attacks, Elizabeth Short underwent lung surgery at age 15, after which doctors suggested she periodically relocate to a milder climate to prevent further respiratory problems. Her mother sent her to spend winters with family and friends in Miami, Florida, for the next three years. She dropped out of Medford High School during her sophomore year.

In late 1942, Short’s mother received a letter of apology from her presumed-deceased husband, which revealed that he was, in fact, alive and had started a new life in California. In December, at age 18, Short relocated to Vallejo, California, to live with her father, whom she had not seen since age six. At the time, he worked at the nearby Mare Island Naval Shipyard on San Francisco Bay. Arguments between Short and her father led to her moving out in January 1943.

Short took a job at the PX Store at Camp Cooke near Lompoc, briefly living with a U.S. Army Air Force sergeant who reportedly abused her. She left Lompoc in mid-1943 and moved to Santa Barbara, where she was arrested on September 23, 1943, for underage drinking at a local bar. Juvenile authorities sent her back to Massachusetts, but she returned to Florida instead, occasionally visiting her family near Boston.

While in Florida, Short met Major Matthew Michael Gordon Jr., a decorated Army Air Force officer of the 2nd Air Commando Group, who was training for deployment to the Southeast Asian theater of World War II. Short later told friends that Gordon had written to propose marriage while recovering from injuries from a plane crash in India. She accepted his offer, but Gordon died in a second crash on August 10, 1945.

In July 1946, she relocated to Los Angeles to visit Army Air Force Lieutenant Joseph Gordon Fickling, an acquaintance from Florida stationed at the Naval Reserve Air Base in Long Beach.

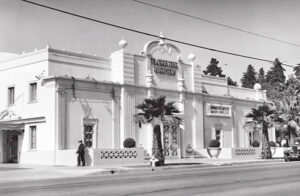

Shortly before her death, she had been working as a waitress and rented a room behind the Florentine Gardens nightclub on Hollywood Boulevard. She was also described as an aspiring actress.

On January 9, 1947, Short returned to her home in Los Angeles after a brief trip to San Diego with Robert “Red” Manley, a 25-year-old married salesman she had been dating. Manley stated that he dropped Short off at the Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, where Short was to meet her sister, who was visiting from Boston that afternoon. By some accounts, staff of the Biltmore recalled having seen Short using the lobby telephone. Shortly after, she was allegedly seen by Crown Grill Cocktail Lounge patrons at 754 South Olive Street, less than a half mile away from the Biltmore.

Just before 11 a.m. on January 15, 1947, a mother walking her child in a Los Angeles neighborhood found Short’s naked body. The body was just a few feet from the sidewalk and posed in the grass in such a way that the woman reportedly first thought it was a mannequin. Elizabeth Short’s body had been severed into two pieces and was found in a vacant lot on the west side of South Norton Avenue, midway between Coliseum Street and West 39th Street in the neighborhood of Leimert Park. Despite the extensive mutilation and cuts on the body, there wasn’t a drop of blood at the scene, indicating Short had been killed elsewhere.

Short’s severely mutilated body was completely severed at the waist and drained of blood, leaving her skin a pallid white. Medical examiners determined that she had been dead for around ten hours before the discovery, leaving her time of death either sometime during the evening of January 14 or the early morning hours of January 15. The killer had washed the body. Short’s face had been slashed from the corners of her mouth to her ears, creating an effect known as the “Glasgow smile.” She had several cuts on her thigh and breasts, where entire portions of flesh had been sliced away. The lower half of her body was positioned a foot away from the upper, and her intestines had been tucked neatly beneath her buttocks. The corpse had been “posed,” with her hands over her head, her elbows bent at right angles, and her legs spread apart.

She acquired the nickname of the Black Dahlia posthumously, as newspapers of the period often nicknamed particularly lurid crimes. After discovering her body, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) began an extensive investigation that produced over 150 suspects but yielded no arrests.

Los Angeles Herald-Express reporter Aggie Underwood was among the first to arrive and took several photos of the corpse and crime scene. Near the body, detectives located a heel print on the ground amid the tire tracks and a cement sack containing watery blood.

An autopsy of Short’s body was performed on January 16, 1947, that stated Short was 5 feet 5 inches tall, weighed 115 pounds, and had light blue eyes, brown hair, and badly decayed teeth. There were ligature marks on her ankles, wrists, and neck and an “irregular laceration with superficial tissue loss” on her right breast. It also noted superficial lacerations on the right forearm, left upper arm, and the lower left side of the chest.

The body had been entirely cut in half by a technique taught in the 1930s called a hemicorporectomy. Little bruising along the incision line suggested it had been performed after death. The lacerations on each side of the face, which extended from the corners of the lips, were measured at three inches on the right side and 2.5 inches on the left. The skull was not fractured, but bruising was noted on the front and right side of her scalp, with a small amount of bleeding consistent with blows to the head. The cause of death was determined to be hemorrhaging from the lacerations to her face and the shock from blows to the head and face. Some signs suggested that she might have been raped, but body samples testing for the presence of sperm were negative.

Short was identified after her fingerprints were sent to the Federal Bureau of Investigation; her fingerprints were on file from her 1943 arrest. Immediately following Short’s identification, reporters from William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner contacted her mother, Phoebe Short, in Boston and told her that her daughter had won a beauty contest.

Only after prying as much personal information as they could from Phoebe did the reporters reveal that her daughter had been murdered. The Examiner also offered to pay for Phoebe’s airfare and accommodations if she would travel to Los Angeles to help with the police investigation. However, that was another ploy since the newspaper kept her away from police and other reporters to protect its scoop.

The Examiner and another Hearst newspaper, the Herald-Express, later sensationalized the case, with one Examiner article describing the black tailored suit Short was last seen wearing as “a tight skirt and a sheer blouse.” The media nicknamed her the “Black Dahlia” and described her as an “adventuress” who “prowled Hollywood Boulevard.” Additional newspaper reports, such as one published in the Los Angeles Times on January 17, deemed the murder a “sex fiend slaying.”

Short was interred at the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California

On January 21, 1947, a person claiming to be Short’s killer placed a phone call to the office of James Richardson, the editor of the Examiner, congratulating Richardson on the newspaper’s coverage of the case and stating he planned on eventually turning himself in, but not before allowing police to pursue him further. Additionally, the caller told Richardson to “expect some souvenirs of Beth Short in the mail.”

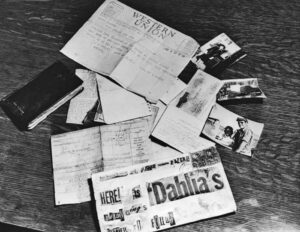

On January 24, a suspicious manila envelope was discovered, addressed to “The Los Angeles Examiner and other Los Angeles papers,” with individual words that had been cut-and-pasted from newspaper clippings; additionally, a large message on the face of the envelope read: “Here is Dahlia’s belongings, letter to follow.” The envelope contained Short’s birth certificate, business cards, photographs, names written on pieces of paper, and an address book with the name Mark Hansen embossed on the cover. The packet had been carefully cleaned with gasoline, similar to Short’s body, which led police to suspect the packet had been sent directly by her killer. Despite efforts to clean the packet, several partial fingerprints were lifted from the envelope and sent to the FBI for testing; however, the prints were compromised in transit and thus could not be adequately analyzed. The same day the Examiner received the packet, a handbag, and a black suede shoe were seen on top of a garbage can in an alley a short distance from Norton Avenue, two miles from the crime scene. Police recovered the items, but they had also been wiped clean with gasoline, destroying any fingerprints.

On February 2, 1947, just two weeks after Short’s murder, Republican state assemblyman C. Don Field was prompted by the case to introduce a bill calling for the formation of a sex offender registry, and the state of California would become the first U.S. state to make the registration of sex offenders mandatory.

On March 14, an apparent suicide note scrawled in pencil on a bit of paper was found tucked in a shoe in a pile of men’s clothing by the ocean’s edge at the foot of Breeze Avenue in Venice. The note read: “To whom it may concern: I have waited for the police to capture me for the Black Dahlia killing but have not. I am too much of a coward to turn myself in, so this is the best way out for me. I couldn’t help myself for that or this. Sorry, Mary.” The pile of clothing was first seen by a beach caretaker, who reported the discovery to lifeguard captain John Dillon. Dillon immediately notified Captain L.E. Christensen of West Los Angeles police station. The clothes included a coat and trousers of blue herringbone tweed, a brown and white T-shirt, white jockey shorts, tan socks, and tan moccasin leisure shoes, size about eight. The clothes gave no clue about the identity of their owner.

Police quickly deemed Mark Hansen, the owner of the address book in the packet, a suspect. Hansen was a wealthy local nightclub and theater owner and an acquaintance at whose home Short had stayed with friends. According to some sources, Hansen also confirmed that the purse and shoe discovered in the alley were, in fact, Short’s. Ann Toth, Short’s friend and roommate, told investigators that Short had recently rejected sexual advances from Hansen and suggested it as a potential motive for him to kill her; however, he was cleared of suspicion in the case.

In addition to Hansen, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) interviewed over 150 men in the ensuing weeks whom they believed to be potential suspects. Robert M. “Red” Manley, one of the last people to see Short alive, was also investigated but was cleared of suspicion after passing numerous polygraph examinations. Police also interviewed several people found listed in Hansen’s address book, including Martin Lewis, who had been an acquaintance of Short’s. Lewis was able to provide an alibi for the date of Short’s murder, as he was in Portland, Oregon, visiting his dying father-in-law.

A total of 750 investigators from the LAPD and other departments worked on the case during its initial stages, including 400 sheriff’s deputies and 250 California State Patrol officers. Various locations were searched for potential evidence, including storm drains throughout Los Angeles, abandoned structures, and various sites along the Los Angeles River, but the searches yielded no further evidence. City councilman Lloyd G. Davis posted a $10,000 reward for information leading police to Short’s killer. After the reward was announced, various people came forward with confessions, most of which police dismissed as false. Several of the false confessors were charged with obstruction of justice.

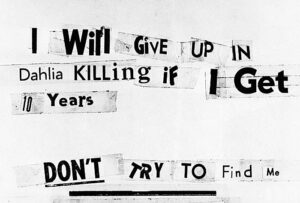

On January 26, the Examiner received another letter, this time handwritten, which read: “Here it is. Turning in Wed., Jan. 29, 10 a.m. Had my fun at police. Black Dahlia Avenger”. The letter also named a location where the supposed killer would turn himself in. Police waited at the location on the morning of January 29, but the alleged killer did not appear. Instead, at 1:00 p.m., the Examiner’s offices received another cut-and-pasted letter, which read: “Have changed my mind. You would not give me a square deal. Dahlia killing was justified.”

The graphic nature of the crime and the subsequent letters received by the Examiner had resulted in a media circus surrounding Short’s murder. Both local and national publications covered the story heavily, many of which reprinted sensationalistic reports suggesting that Short had been tortured for hours before her death; the information, however, was false, yet police allowed the reports to circulate to conceal Short’s actual cause of death — cerebral hemorrhage — from the public.

Further reports about her personal life were publicized, including details about her alleged declining of Hansen’s sexual advances; additionally, a stripper who was an acquaintance of Short’s told police that she “liked to get guys worked up over her, but she’d leave them hanging dry.” This led some reporters and detectives to look into the possibility that Short was a lesbian and begin questioning employees and patrons of gay bars in Los Angeles; this claim, however, remained unsubstantiated. The Herald-Express also received several letters from the purported killer, again made with cut-and-pasted clippings, one of which read: “I will give up on Dahlia killing if I get 10 years. Don’t try to find me.”

On February 1, the Los Angeles Daily News reported that the case had “run into a Stone Wall” with no new leads for investigators to pursue. The Examiner continued to run stories on the murder and the investigation, which was front-page news for 35 days after discovering the body.

When interviewed, lead investigator Captain Jack Donahue told the press that he believed Short’s murder had occurred in a remote building or shack on the outskirts of Los Angeles and that her body was transported into the city where it was disposed of. Based on the precise cuts and dissection of Short’s body, the LAPD looked into the possibility that the murderer had been a surgeon, doctor, or someone with medical knowledge. In mid-February 1947, the LAPD served a warrant to the University of Southern California Medical School, located near the site where the body had been discovered, requesting a complete list of the program’s students. The university agreed so long as the students’ identities remained private. Background checks were conducted but yielded no results.

By the spring of 1947, Short’s murder had become a cold case with few new leads. Sergeant Finis Brown, one of the lead detectives on the case, blamed the press for compromising the investigation through journalists’ probing of details and unverified reporting. In September 1949, a grand jury convened to discuss inadequacies in the LAPD’s homicide unit based on their failure to solve numerous murders — especially those of women and children — in the previous several years, Short’s being one of them. In the aftermath of the grand jury, further investigation was done on Short’s past, with detectives tracing her movements between Massachusetts, California, and Florida and interviewing people who knew her in Texas and New Orleans, Louisiana. However, the interviews yielded no helpful information about the murder.

Although never formally charged with the crime, George Hodel came to authorities’ attention after his death when he was accused by his son, LAPD homicide detective Steve Hodel, of killing Short and committing several additional murders. Before the Dahlia case, he was suspected, but not charged, in the death of his secretary, Ruth Spaulding; and was accused of raping his own daughter, Tamar, but acquitted. Hodel fled the country several times and lived in the Philippines between 1950 and 1990. Additionally, Steve Hodel has cited his father’s training as a surgeon as circumstantial evidence. In 2003, it was revealed in notes from the 1949 grand jury report that investigators had wiretapped Hodel’s home and obtained recorded conversation of him with an unidentified visitor, saying: “Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia. They couldn’t prove it now. They can’t talk to my secretary because she’s dead. They thought there was something fishy. Anyway, now they may have figured it out. Killed her. Maybe I did kill my secretary.”

In 1991, Janice Knowlton, who was ten years old at the time of Short’s murder, claimed that she witnessed her father, George Knowlton, beat Short to death with a claw hammer in the detached garage of her family’s home in Westminster. She also published a book titled Daddy was the Black Dahlia Killer in 1995, claiming her father sexually molested her. The book was condemned as “trash” by Jolane Emerson, Knowlton’s stepsister, who stated: “She believed it, but it wasn’t reality. I know because I lived with her father for sixteen years.” Additionally, Detective St. John told the Times that Knowlton’s claims were “not consistent with the facts of the case.”

In 2000, Buz Williams, a retired detective with the Long Beach Police Department, wrote an article for the LBPD newsletter The Rap Sheet on Short’s Murder. His father, Richard F. Williams, and his friend, Con Keller, were both members of the LAPD’s Gangster Squad investigating the case. Williams’ father believed that lifeguard captain John Dillon was the killer and that when Dillon returned to his home state of Oklahoma, he was able to avoid extradition to California because his ex-wife Georgia Stevenson was second cousins with Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson II, who contacted the governor of Oklahoma on Dillon’s behalf. Keller believed Mark Hansen was the killer, as he had studied at a surgical school in Sweden and had thrown elaborate parties attended by prominent LAPD officials. Williams’ article says that Dillon sued the LAPD for $3 million but that the suit was dropped. Harnisch disputes this, claiming that police cleared Dillon after an exhaustive investigation and that the district attorney’s files positively placed him in San Francisco when Short was killed. Harnisch claims that there was no LAPD coverup and that Dillon did receive a financial settlement from the City of Los Angeles but has not produced concrete evidence to prove this.

In 2003, Ralph Asdel, one of the original detectives on the case, told the Times that he believed he had interviewed Short’s killer. This man had been seen with his sedan parked near the vacant lot where her body was discovered in the early morning of January 15, 1947. A neighbor driving that day stopped to dispose of a bag of lawn clippings in the lot when he saw a parked sedan, allegedly with its right rear door open; the driver was standing in the lot. His arrival apparently startled the owner of the sedan, who approached his car and peered in the window before returning to the sedan and driving away. The sedan owner was followed to a local restaurant where he worked but was cleared of suspicion.

The 2017 book Black Dahlia, Red Rose by Piu Eatwell focuses on Leslie Dillon, a bellhop who was a former mortician’s assistant; his associates Mark Hansen and Jeff Connors; and Sergeant Finis Brown, a lead detective who had links to Hansen and was allegedly corrupt. Eatwell posits that Short was murdered because she knew too much about the men’s involvement in a scheme for robbing hotels. She further suggests that Short was killed at the Aster Motel in Los Angeles, where the owners reported finding one of their rooms “covered in blood and fecal matter” on the morning Short’s body was found. The Examiner stated in 1949 that LAPD chief William A. Worton denied that the Aster Motel had anything to do with the case. However, its rival newspaper, the Los Angeles Herald, claimed the murder occurred there.

While there are numerous theories about what truly happened to 22-year-old Hollywood hopeful Elizabeth Short, the case remains unsolved. Her unsolved murder and details have had a lasting intrigue, generating various theories and public speculation. Her life and death have been the basis of numerous books and films, and her murder is frequently cited as one of the most famous unsolved murders in U.S. history, as well as one of the oldest unsolved cases in Los Angeles County. Historians have likewise credited it as one of the first major crimes in postwar America to capture national attention.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See:

Sources: