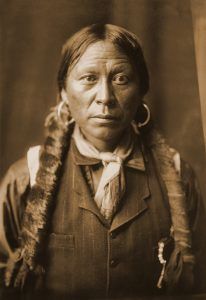

The Jicarilla Apache roamed over much of northern New Mexico. Nominally at peace during the early 1850s, they grew increasingly restive. Small war parties raided outlying settlements and caravans on the Santa Fe Trail northeast of Fort Union. By 1854, their forays approached open war.

Late in February 1854, Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, commanding Fort Union, sent Lieutenant David Bell and a company of the 2d Dragoons east to the Canadian River to investigate reports of Jicarilla plundering the cattle herd of Samuel Watrous, who supplied Fort Union with beef. On March 2nd, Bell’s 24 horsemen clashed with an equal number of Apache under Lobo Blanco, killed five (including the chief), and wounded more before the Indians fled.

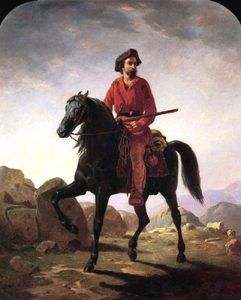

A month later, a large force of Apache ambushed a company of 62 dragoons under Lieutenant John W. Davidson on the road between Taos and Santa Fe. Davidson left the field with 22 dead and 36 wounded. These incidents impelled the department commander, Brigadier General John Garland, to launch a full-scale offensive against the offenders. Within three hours after learning of the Davidson disaster, Colonel Cooke had set the garrison of Fort Union in motion for Taos. There, he organized a force of 200 dragoons and footmen and enlisted 30 Pueblo Indian scouts. Guided by Kit Carson, agent for the Ute tribe, the command crossed the Rio Grande and plunged into the forbidding mountains, still white with the last touches of winter.

Canadian River, New Mexico by SR Euston, courtesy Wander West

On April 8th, the pursuers overtook a band of 150 Indians under Chief Chacon, who had posted his men among rocks and trees on a slope at the foot of which ran the snow waters of the Rio Caliente. The troops waded the icy stream and swarmed up the mountainside, Lieutenant Bell’s company swinging to the left and catching the enemy line in the flank. Resistance dissolved, and the warriors scattered through the timber with casualties of five killed and six wounded. The attackers lost one killed and one wounded. For a month, Cooke marched and countermarched in a vain effort to overtake the Indians once more. The rugged mountains, swept by blizzards, cloaked in fog, and buried under drifts of snow, soon exhausted and sickened the command. Himself ill, Cooke called off the chase.

The Apache were scarcely less worn out. Many gave up, but a few diehards continued to terrorize the countryside. The following July, Capt. George Sykes and 58 dragoons from Fort Union picked up the trail of one such war party and followed it into the mountains west of the fort.

Riding down the canyon floor, they flushed 10 or 15 Indians, who spurred their ponies up the side of the gorge. Lieutenant Joseph Maxwell and 20 dragoons charged up the slope in pursuit. The lieutenant and four men reached the top first and found themselves suddenly in the midst of eight warriors hidden among some rocks. As Maxwell swung his saber overhead, the Apache loosed a volley of arrows. Two found their mark and killed him instantly. The war party made good its escape, and the dragoons returned to Fort Union with the body of the young officer. “I have no words,” Captain Sykes reported to Colonel Cooke, “to express my feelings in making this announcement, braver, gallant or more high-toned gentlemen and soldier never drew a sword.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Indian Wars, Battles & Massacres

Winning The West: The Army In The Indian Wars

Source: National Park Service