By Charles Martin in 1862

I will tell you what I saw at Newport News, Virginia when the Merrimac destroyed the Congress and the Cumberland and fought with the Monitor. It was a drama in three acts, and 12 hours will elapse between the second and third acts.

“Let us begin at the beginning” — 1861. The North Atlantic squadron is at Hampton Roads, except the frigate Congress and the razee Cumberland; they are anchored at Newport News, blockading the James River and Norfolk. The Merrimac, the rebel ram, is in the dry dock of the Norfolk navy yard. The Merrimac had been a wooden vessel in the old navy but was cut down — and built up with sloping bow plates.

The Monitor was built in New York City. It is determined to keep the Merrimac in the dry dock, wait for the arrival of the Monitor, and send her out to meet her. In action, it is positive that an opportunity will be offered to pierce and sink her. The ram is a terror, and both sides say, “When the Merrimac comes out!” On the last of February 1862, the Monitor is ready for sea; she will sail for Hampton Roads in charge of a steamer. There is a rumor that she has broken her steering gear before reaching Sandy Hook. She will be towed to Washington, D.C., for repairs. The Rebel spies report her a failure- the steering is defective, and the turret revolves with difficulty. When the smoke of her guns in action is added to the ventilation defects, it will be impossible for human beings to live aboard her. No Monitor to fight, the Southern press and people grumble; they pitch into the Merrimac. Why does she lie idle? Send her out to destroy the Congress and the Cumberland, that have so long bullied Norfolk, then sweep away the fleet at Hampton Roads, starve out Fortress Monroe, go north to Baltimore and New York and Boston, and destroy and plunder; and the voice of the people, not always an inspiration, prevails, and the ram is floated and manned and armed, and March 8 is bright and sunny when she steams down the Elizabeth River to carry out the first part of her program.

All Norfolk and Portsmouth ride and run to the bank of the James River to have a picnic and assist at a naval battle and victory. The cry of “Wolf!” has so often been heard aboard the ships that the Merrimac has lost much of her terrors. They argue: “If she is a success, why doesn’t she come out and destroy us?” And when seen this morning at the mouth of the river: “It is only a trial trip or a demonstration.” But she creeps along the opposite shore, and both ships beat to quarters and get ready for action. The boats of the Cumberland are lowered, made fast to each other in line, anchored between the ship and the shore, about an eighth of a mile distant.

Here are two large sailing frigates on a calm day, at slack water, anchored in a narrow channel, impossible to get under weigh and maneuver, must lie and hammer, and be hammered, so long as they hold together, or until they sink at their anchors. To help them is a tug, the Zouave, once used in the basin at Albany to tow canal boats under the grain elevator. The Congress is the senior ship; the tug makes fast to her. The Congress slips her cable and tries to get underweight. The tug does her best and breaks her engine. The Congress goes aground in line with the shore. The Zouave floats down the river, firing her pop guns at the Merrimac as she drifts by her. The command of both the ships devolves on the first lieutenants. Onboard the Cumberland, all hands are allowed to remain on deck, watching the slow approach of the Merrimac, and she comes on so slowly that the pilot declares she has missed the channel; she draws too much water to use her ram. She continues to advance, and two gunboats, the Yorktown and the Teaser, accompany her. Again, they beat to quarters, and everyone goes to his station. There is a platform on the Merrimac roof. Her captain is standing on it. When she is near enough, he hails, “Do you surrender? “Never!” is the reply.

The order to fire is given; the starboard battery shot rattles on the Merrimac’s iron roof. She answers with a shell; it sweeps the forward pivot gun, and it kills and wounds ten of the gun’s crew. A second slaughters the marines at the after-pivot gun. The Yorktown and the Teazer keep up a constant fire. She bears down on the Cumberland. She rams her just aft the starboard bow. The ram goes into the ship’s sides as a knife goes into cheese. The Merrimac tries to back out; the tide is making; it catches against her great length at a right angle with the Cumberland; it slews her around; the weakened, lengthened ram breaks off; she leaves it in the Cumberland. The battle rages, broadside answers broadside, and the sanded deck is red and slippery with the blood of the wounded and dying; they are dragged amidships out of the way of the guns; there is no one and no time to take them below. Delirium seizes the crew; they strip to their trousers, tie their handkerchiefs around their heads, kick off their shoes, fight and yell like demons, load, and fire at will, keep it tip for the rest of the forty-two minutes the ship is sinking, and fire and the last gun as the water rushes into her ports.

The Merrimac turns to the Congress. She is aground, but she fires her guns till the red-hot shot from the enemy sets her on fire, and the flames drive the men away from the battery. She has forty years of seasoning; she burns like a torch. Her commanding officer is killed, and her deck is strewn with killed and wounded. The wind is offshore; they drag the wounded under the windward bulwark, where all hands take refuge from the flames. The sharpshooters on shore drive away a tug from the enemy. The crew and wounded of the Congress are safely landed. She burns the rest of the afternoon and evening, discharging her loaded guns over the camp. At midnight, the fire reached her magazines, and Congress disappeared.

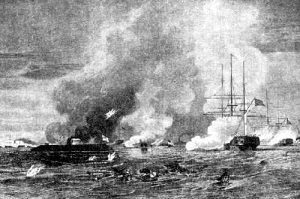

When it is signaled to the fleet at Hampton Roads that the Merrimac has come out, the Minnesota leaves her anchorage and hastens to join the battle. Her pilot puts her aground off the Elizabeth River, and she lies there helplessly. The Merrimac has turned back for Norfolk. She has suffered from the shot of the Congress and the Cumberland, or she would stop and destroy the Minnesota; instead, with the Yorktown and Teazer, she goes back into the river. Sunday morning, March 9, the Merrimac is coming out to finish her work. She will destroy the Minnesota. As she nears her, the Monitor appears from behind the helpless ship; she has slipped in during the night and so quietly, her presence is unknown in the camp. And David goes out to meet Goliath, and every man who can walk to the beach sits down there, spectators of the first ironclad battle in the world. The day is calm, the smoke hangs thick on the water, the low vessels are hidden by the smoke. They are so sure of their invulnerability that they fight at arm’s length. They fight so near the shore that the flash of their guns is seen, and the noise of the heavy shot is heard pounding the armor.

The Merrimac never tried another fight and was at last destroyed by the rebels. The Merrimac stops firing, the smoke lifts, and she runs down the Monitor, but she has left her ram in the Cumberland. The Monitor slips away, turns, and renews the action. One p.m. — they have fought Since 8.30 a.m. The crews of both ships are suffocating under the armor. The frames supporting the iron roof of the Merrimac are sprung and shattered. The turret of the Monitor is dented with a shot and is revolved with difficulty. The captain of the Merrimac is wounded in the leg; the captain of the Monitor is blinded with powder. It is a drawn game. The Merrimac, leaking badly, goes back to Norfolk; the Monitor returns to Hampton Roads.

By Charles Martin, 1862. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Source: The Little Monitor and the Merrimac was written by Charles Martin in 1862 and included in Albert Bushnell Hart’s The Romance of the Civil War, published in 1896. The work is now in the public domain.

Editors Note: The battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac was the first between two ironclad ships of war. It occurred on March 9, 1862, in Hampton Roads, Virginia.

The Monitor and the Merrimac, by Currier & Ives, 1862

Also See:

Historical Accounts of American History

Civil War (main page)

American History (main page)