By Joseph P. Sánchez

Spanish Missions are rich cultural landscapes that span the spectrum of mission development from isolated and quickly abandoned chapels to comprehensive, self-sustaining communities covering hundreds of acres. The Spanish government and religious orders established missions to convert existing populations to Roman Catholicism. The Missions were located adjacent to established native settlements that provided labor for mission construction and maintenance. Some mission communities were near dispersed agrarian communities, while others were in the center of the most densely formed native settlements. Regardless of its size, at the core of every mission community was a church building as its spiritual center. Often beginning as no more than a temporary shelter from which to celebrate mass, the church building and later support structures evolved as the population of converts grew and resources for construction became available.

Architecture of Mission Communities

The architectural styles of Spanish Colonial missions were influenced by those popular in Spain and Europe — Gothic, Baroque, Plateresque, Mudéjar, Churrigueresque, Neoclassicism — but their application in the Americas cannot be fit easily into any specific stylistic category. The local context of available materials, labor, and technical expertise challenged the Spanish frontier builders to find the expertise to interpret their foreign cultural expression. As a result, mission architecture evolved into a fusion of imported and indigenous expressions that are unique to each mission,

The Church

Mission priests modeled church plans after Old World churches with which they were familiar. The hall church was composed of a tall rectangular room divided into the nave space for the worshipers and the sanctuary where the clergy celebrated mass. The sanctuary is the most sacred of the church as it holds the altar and is often elevated above the nave. The sanctuary is located within the apse, a polygonal or semi-circular space at the end of the nave, the visual focal point for worshipers entering the church.

The cruciform church plan is a Latin cross with the bottom portion designated as the nave, the upper portion as the apse housing the sanctuary, and transepts on either side of the crossing containing chapels. Above the crossing, a hemispherical dome typically covers the sanctuary, symbolizing celestial heaven. The sacristy, a private room where sacred objects are stored, and the clergy robes his vestments, is connected to the sanctuary. Other distinct spaces within the church building include a baptistery located next to the nave and a choir loft above the church entry foyer. In Europe, church plans are typically oriented with worshippers facing east, the direction of the rising sun, and symbolizing the Risen Christ. In New World mission churches, however, orientation varies extensively and without consistency.

Ornamentation

For worshippers, ornamentation in mission architecture played two significant functions. Architectural features — entablatures, pilasters, window surrounds, columns, beams, and surface decoration — were integral to the church designs. Builders used these features to reinforce stylistic expressions using stone, molded brick, plaster, wood, ceramic tile, and pigment. Sacred ornamentation — figures of saints, altar screens, paintings, and stencil designs — became important teaching tools. Priests also used these features to transform the church into a colorful three-dimensional religious textbook for new converts. Among these features, the monumental altar screen in the church apse focused on elaborate decoration and a canvas of religious symbols or icons. These icons acted as objects of both inspirational worship and moral instruction. In practice, Christian iconography was not always purely applied but often blended with native symbols and executed by native artisans. The resulting hybrid product reflected priests’ attempts to attract and integrate native populations and their representational art forms.

Priests and master builders designed mission churches to manipulate sunlight for ornamental and religious purposes. Light is channeled to illuminate symbolically the sanctuary, its source unseen by the worshiper in the nave. Mission churches with domed roofs over the sanctuary have windows incorporated in the dome’s base or as a lantern atop the dome, distributing a uniform light onto the altar. In New Mexican flat-roofed hall churches, a narrow upper window between the nave roof and the raised apse roof creates a horizontal band of light shining directly on the altar screen. Some are oriented precisely to have direct light cast on a figure of the church’s patron saint, usually the centerpiece of the altar screen, on his saint day.

Exterior

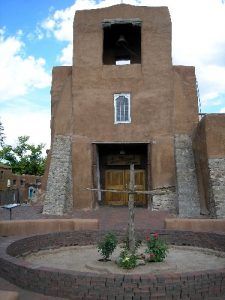

The exterior character of many frontier missions is utilitarian as the buildings often served defensive and religious purposes. The exception to this is the principal entry façade – a critical architectural element that communicated the mission’s status and focused on the building’s exterior ornamentation. An imposing presence in native communities, the typical principal façade of a mission church has three major components: the entry doorway, the frontispiece surrounding it, and the bell towers extending vertically above the rest of the building. The amount of ornamentation in each of these components varies depending on the church. At its most elaborate, the principal façade reflects the rich ornamentation of the interior altar screen. Like other forms of ornamentation, the principal façade conveys the elements of the church’s stylistic language and religious message but directed outward to the community. Priests and master-builders used geometric principles and proportional relationships, symbolizing divine order, as design tools in the composition of the principal façade. These geometries on the vertical face of the exterior often are translated directly to the horizontal layout of the interior plan.

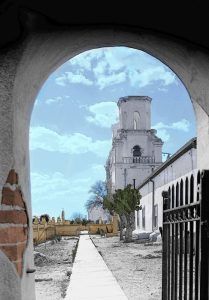

Not present in all mission churches, the bell tower takes on many forms. Single or twin towers often flank the principal façade or were independent, detached structures. Characteristic of many New Mexican mission churches, the twin bell towers extend outward to frame the entry facade, and spanning between them is a wooden balcony used for outdoor ceremonies. Missions that lacked resources to build towers had elaborate bell gables (espadañas) with multiple arched openings containing bells, either incorporated into the principal facade or built as a detached structure. These bell gables have become one of the most enduring and idealized images of mission architecture.

Building Materials

Availability of local building materials often dictated the church’s construction system. In some cases, mission churches reflect the construction materials of the native communities, seen as both a gesture of assimilation and practical use of local technical expertise. Sun-dried adobe, composed of clay, silt, and sand, is the most common of mission construction materials. It required the least amount of resources and was most closely aligned with the native use of puddled mud. Fired brick required access to good clay and the fuel resources, primarily wood from forested areas to kiln-fire the bricks. Used where it was available, cut stone, such as limestone in Texas and sandstone in New Mexico, required the establishment of quarries. These quarries, and the production technologies to extract, finish, and lay their stone, became yet another fingerprint on the Spanish Colonial cultural landscape. Other church buildings have composite wall systems — cut stone or fired clay brick outer walls with rubble stone and lime slurry filling the core — reflecting technical knowledge of European construction systems that date to the Roman Empire.

The availability of building materials and technical expertise influenced the building’s size and the architectural character of mission churches in each region. Access to stone or bricks permitted European-inspired dome or vaulted roof construction that could span wide naves. This construction system also required thick exterior walls and even buttresses to support the outward thrust of these heavy roofs. Where only wood was available, the width of the nave depended on the span capacity of the heavy timber used in both flat and pitched roofs. Flat roofs required a layered system, not unlike native construction systems. They consisted of primary structural wood beams, secondary members — often branches of available vegetation — laid perpendicular to the beams and topped with packed earth. Pitched roofs were in use where rain was more prevalent. These required a framework of heavy timber primary beams and rafters, along with secondary purlins on which either straw thatch or clay barrel tiles were attached. Heavy timber for roof construction was difficult to find in the deserts of Texas and Arizona but was more abundant in the forested areas of California and New Mexico.

The exterior finishes of mission churches often depended on the durability of the structural wall materials used. Adobe required the building to be sheltered from damaging rainwater, either protected with deeply overhanging pitched roofs or covered with lime or mud plaster. Even the type of mortar and plaster depended on the availability of the raw materials and the resources and expertise to process them.

Mission Complex

Beyond the church building, missions also included several buildings, structures, features, and open spaces. Each contributed to the establishment of a community whose day-to-day functions were to serve the Spanish colonial enterprise.

At its full extent, the complex immediately surrounding the mission church had a “friary plan” layout centered on a courtyard, or garth, defined by the church on one side and a series of one- or two-story buildings, creating the mission quadrangle. The friary plan was often applied to sites that required the mission complex to provide a defensive and practical function. The most important quadrangle section was the priests’ residence that contained living quarters, a kitchen, and administrative offices. Other sections included classrooms, storage, and workshops for various crafts. The open courtyard varied in size but typically contained a lush environment of trees, gardens, and fountains that provided a tranquil respite and food and commodities for the mission community. The interior courtyard was often an arcade and corridor that provided a shaded walkway and work area for its activities.

New Mexican mission sites typically had a forecourt in front of the church entrance that provided a space for outdoor ceremonies intended for large audiences. During these ceremonies –including conversions, feast day pageants, processions, and even mass –the church’s principal façade acted as an outdoor altar screen. The size of the entrance hall varies but is defined by a perimeter wall that typically extends around the entire church property containing a gate aligned with the church entry.

In larger mission communities, the architectural footprint extended beyond the immediate church complex. There were separate buildings and open spaces designated for specific sacred functions — cemeteries and mortuary chapels — and production functions –granaries, tanneries, gristmills, blacksmiths, carpentry shops, and kilns for the firing of brick and lime. The mission cultural landscape may also include subtle but no less significant features, including neophyte (recent native converts) housing, corrals, orchards, cultivated fields, and open range to support cattle, goats, and sheep. Some mission complexes even built protective perimeter walls, with formal entry gates and bastions, to protect against raiding tribes.

At their full extent, mission communities incorporated a sophisticated irrigation infrastructure. Wells, canals, dams, aqueducts, and floodgates diverted, transported, and controlled the water from its source to the agricultural fields, orchards, livestock pens, gardens, fountains, and community washing areas. For the original native communities, their long-term survival depended on the proximity to a reliable natural water source and the technological skills to distribute it. Subsequent Spanish Colonial mission communities often inherited this water infrastructure and enhanced it to serve a more complex array of land and community uses. This irrigation infrastructure was a vital yet often over-shadowed component of the layered mission cultural landscape.

Preservation

Spanish Colonial mission cultural landscapes express a strong connection between the natural environment of each distinct region and the subsequent layers of human settlement over time. The preservation of these cultural landscapes and the complex set of values they represent has required an integrative approach to determining their significance, conservation treatments, and stewardship strategies to ensure each site’s viability for current and future generations.

Scholarly understanding of the Spanish colonial enterprise’s impact in the Americas, which mission architecture represents, continues to evolve. Viewing missions as part of a comprehensive cultural landscape helps us tell their complex stories from multiple viewpoints and understand the impact of colonialism on native communities. This has required an inclusive approach to recognizing and preserving various mission features to interpret this complex historical narrative. Contemporary property boundaries and the encroachment of cities and suburbs into many of the original mission communities complicate the challenge of preserving these formerly vast cultural landscapes. Such urbanization often means the destruction of outlying mission features that erases part of the complete story of the Spanish colonial enterprise.

Our approach to conserving mission buildings has also evolved, leading ultimately to the development of current federal and international preservation standards. The earliest managers and custodians of missions experimented with heavy-handed conservation treatments. This resulted in the creation of romantically idealized mission environments and modern construction materials that often proved detrimental to the historic architecture. Today, these sites benefit from internationally recognized preservation standards, including a more systematic process of comprehensive documentation, historical scholarship, materials analysis, and conservation treatments using compatible and often traditional building materials and techniques. Spanish Colonial mission sites represent some of the United States’ oldest standing architecture and continue to provide technical preservation challenges. Today, however, managers of mission sites are equipped with conservation practices focused on the authenticity of the preservation process.

Stewardship of mission sites — actions to ensure long-term sustainability– is often the most complex yet under-recognized facet of preservation. This requires balancing curatorial management of museum-quality art and artifacts, functional requirements of a living parish along with other user groups, tourists’ expectations of access, interpretation, and authenticity of experience, as well as funding challenges to support constant preservation and maintenance efforts. In the United States, the responsibility for stewardship of mission sites rests with many entities, making the multi-faceted preservation challenges sometimes difficult to address. These entities range from federal and state public agencies to individual tribal governments and private religious institutions. The mission sites included in this travel itinerary reflect the diversity of stewardship entities, each with its own approach to interpret, preserve, and manage the unique cultural landscapes of the Spanish colonial enterprise.

By Joseph P. Sánchez, PhD, National Park Service. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander, updated September 2021.

Also See:

A Day in the Life of a Spanish Missionary

Missions & Presidios of the United States