The North Bloomfield Historic District, located in Nevada County, California, about 15 miles northeast of Nevada City, got its start a few years after the California Gold Rush began. A California State Park today, the district includes the workings of Malakoff Diggins adjacent to the ghost town of North Bloomfield and other mining camps, including Lake City, Derbec, and Relief Hill.

In 1851, three prospectors were working their way up from Grass Valley and Nevada City when they discovered gold in a little creek just south of where North Bloomfield would later be established. After working the area for some time, one of the men went to Nevada City for supplies, taking several hundred dollars worth of dust with him. On his arrival, he sold the gold dust, purchased the supplies and a mule to pack them, and got ready to return. However, before he departed, he made one last stop in a saloon. Though he had been sworn to secrecy by his partners, he began to boast of their rich find after several drinks but didn’t disclose the location. The next morning, when he finally departed, he was followed at a distance by many men who were also searching for their share of gold. However, these followers didn’t find any riches in the area and named the stream “Humbug Creek.”

The next year, more miners and settlers came to the region, and soon a settlement called “Humbug City” sprang up. The miners who stayed in the area eventually discovered gold-bearing gravel deposits, and various engineering techniques were created to separate the gold from the rock.

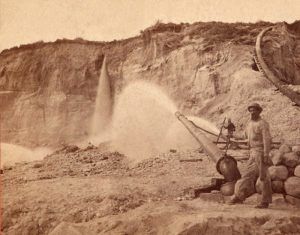

In 1853 hydraulic mining began. This technique utilized high-pressure water jets to dislodge rock material and move sediment. Dams were built high in the mountains, and the water traveled up to 45 miles through flumes. The miners then aimed large nozzles, called monitors, at the hillsides to wash the gravel into huge sluices, where the gold particles, which were heavier than the sludge, separated from the sediments. Once this was complete, the sludge, sediment, and debris were dumped into Humbug Creek using the 600-foot Hiller Tunnel.

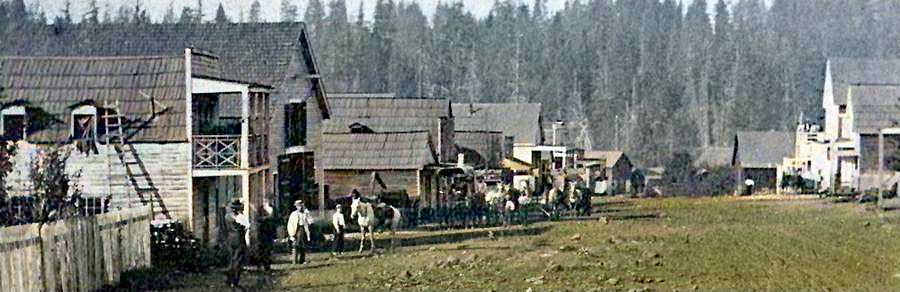

As more manpower was needed for these new operations, the settlement of Humbug became one of the county’s liveliest and most prosperous towns. By 1857 the town had grown to 500 people, and when a post office was established the same year, it was called “North Bloomfield.” Many early miners and settlers were French-speaking pioneers who opened hotels and businesses and planted gardens. Many of the miners began developing claims along the Malakoff Ravine.

By the late 1850s, miners were experimenting with more effective hydraulic methods, increasing the demand for water delivered by ditches, flumes, and pipes. The town of North Bloomfield continued to grow. However, in the early 1860s, hydraulic mining slowed dramatically due to the lack of water during several drought years. At this point, many miners left to work mines in Canada and Nevada. However, one French miner and entrepreneur, Julius Poquillion, who had purchased and consolidated several abandoned claims in the area around North Bloomfield, went to San Francisco to seek investors to start a large-scale hydraulic mining operation.

The North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company was formed in August 1866, and over 1,500 acres were purchased in the Humbug Canyon area of North Bloomfield. The company often referred to as the “French Company,” soon saw the need for a larger and continuous water supply for hydraulic mining and purchased the English Reservoir, the largest reservoir in the state at the time. They also purchased Bowman’s Ranch on Big Canyon Creek as a site for another reservoir and created a ditch system to bring more water to the diggings. Before the company was done, water came from 11 reservoirs, and the total daily water consumption for the company was more than 100 million gallons.

By 1868, the company employed over 800 Chinese and 300 Whites, and the Malakoff Mine became the premier hydraulic mining operation in California. The company used as many as eight monitors simultaneously, fashioned after Civil War cannons. Weighing as much as 1.5 tons, they were capable of using 25 million gallons of water in a 24-hour period.

However, it was quickly evident that Humbug Creek couldn’t handle the volume of sludge, sediment, and debris. It was also found that the Hiller Tunnel, which emptied into Humbug Creek, was not adequate for the advanced operations of the mine. As a result, the North Broomfield Tunnel was engineered, and construction began in 1872. One of the most impressive mining feats of the day, the drainage tunnel was carved from solid bedrock and was 7,878 feet long. After 30 months of men working day and night to complete the tunnel, the water and refuge flowed directly into the South Yuba River in 1874.

By 1876, the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company was in full operation, with employees working 12-hour shifts and operating 24 hours per day, seven days per week, and working 100,000 tons of gravel daily. By this time, it was the largest hydraulic-mining operation in the state. It also boasted over 100 miles of canals, ditches for water transport, and seven full-scale powerful water cannons to scour ore from the mountainside. At this time, the town of Bloomfield supported as many as 2,000 people.

However, millions of tons of cubic yards of tailings, debris, silt, and water from hydraulic operations washed downstream, clogging waterways, raising river levels, and flooding adjacent farms. On one occasion, the city of Marysville flooded when the river bottom rose higher than the town. On another occasion, the city of Sacramento flooded while silt traveled down the American River to San Francisco Bay.

In 1878 the Anti-Debris Commission was formed, and petitions were submitted to Legislature to regulate laws that would control mining operations. Though some laws were instituted, they were ineffective. In September 1882, litigation was brought against the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company by a farmer named Edward Woodruff from the recently flooded town of Marysville.

In January 1884, Judge Lorenzo Sawyer handed down one of the first environmental rulings in the United States, which ordered a permanent injunction against dumping debris into the Yuba River, resulting in the prohibition of hydraulic mining in California.

However, the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company ignored the ruling and continued hydraulic mining at night. In 1886, the company was found in contempt of the Sawyer Act and was fined heavily. The mining company then installed a new system to pull debris from the tailings and retain it in holding ponds. Though this move satisfied the authorities, it greatly hindered the production capabilities and reduced the profit margin of the mining company. By 1890, the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company was the only hydraulic mine operating in the area.

In 1893 Congress passed a law that all hydraulic mines must be licensed, but the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company ignored the ruling. In 1896, the mining company was found in contempt of this law and was fined heavily. As the fines and litigation expenses increased, the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company was forced to cease operations in the late 1890s. They left behind a mining pit that was 6,900 feet long, 3,800 feet wide, and 600 feet deep.

By 1900, the town of North Bloomfield’s population had dropped to 730 due to the mine closure. In 1910, the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company was unincorporated. A few locals illegally operated in the mining pit until about 1930. Over the next years, as the population continued to decline and businesses closed, most buildings were demolished for lumber.

During the nearly 44 years that the mining company was in operation, the company excavated 41 million cubic yards of dirt and gravel from the diggings, taking over 13.5 million dollars in gold from the mountain.

By 1950, less than 20 residents lived in North Broomfield, and Nevada County locals pushed to preserve what remained of the historic district over the next decade. In 1964, the State of California began acquiring parcels in and around North Bloomfield, and the property became the Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park in 1965. The park was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 as the Malakoff Diggins – North Bloomfield Historic District.

Today, it is estimated that 80% of the gold is still present in the Malakoff hills.

The 3,143-acre state park features the old town of North Bloomfield, a museum, and several historic buildings, including homes, a drugstore, a church, a schoolhouse, and more. Visitors can see huge cliffs carved by mighty jets of water. The park also features 20 miles of hiking trails, a picnic area, swimming and fishing, a campground, and rustic cabins that can be rented.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

California Ghost Towns & Mining Camps

California Ghost Town Photo Gallery

Sources:

Friends of North Bloomfield

Hittell, Theodore Henry; History of California, N.J. Stone & Company, 1897

Malakoff Diggins State Park

Online Archive of California

Wikipedia