“Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother 40 whacks. When she saw what she had done, she gave her father 41.”

Lizzie Borden, the only suspect in the ax murders of Andrew and Abby Borden in 1892, was arrested, tried, and acquitted in Fall River, Massachusetts.

Lizzie Andrew Borden was born on July 19, 1860, in Fall River, Massachusetts, to Sarah Anthony Morse Borden and Andrew Jackson Borden. Andrew and Sarah had married on December 25, 1845, and had three children: Emma Lenora on March 1, 1851; Alice Esther on May 3, 1856, who died before she was two years old; and Lizzie in 1860. Sarah Morse died on March 26, 1863, when Lizzie was just 2 ½ years old. On her deathbed, Emma made a promise to her mother that she would always watch over little Lizzie.

On June 6, 1865, Andrew Borden married for a second time to Abigail “Abby” Durfee Gray. They never had any children. Lizzie and her sister, Emma, who was nine years older, lived with their father and stepmother well into adulthood.

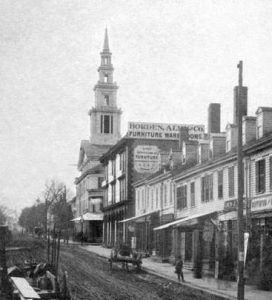

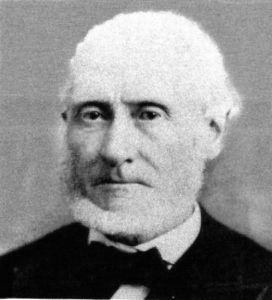

Andrew Jackson Borden descended from a wealthy and influential family, who, by 1714, literally owned much of Fall River. However, as a young man, he grew up in modest surroundings and was apprenticed as a carpenter and helped build the house at 92 Second Street, which he would buy decades later. He would later become an undertaker, and after taking a $1,000 loan, he formed a business partnership with William M. Almy. Both men were undertakers and prospered in manufacturing and selling caskets and furniture.

By the 1850s, Andrew had moved on to property development and later became the president of the Union Savings Bank. He also served as a director for several textile mills, including the Globe Yarn Mill Company and the Troy Cotton and Woolen Manufacturing Company, as well as a director of the Durfee Safe Deposit and Trust Co. and the First National Bank.

In April 1872, Borden purchased the house at 92 Second Street for $10,000 and moved in with his wife and daughters, Emma, who was then 21, and Lizzie, who was 11.

Despite his wealth, Andrew was known for his frugality. Though most of his family lived in a more fashionable neighborhood called “The Hill,” Andrew was content to stay where he was. He also never bothered to upgrade his house with indoor plumbing and electricity that he could have well afforded. The family used oil lamps instead of gas. He was even known to sell eggs from his farm on Main Street. However, he did employ servants to keep their home in order. This frugality was known to have sometimes caused friction in the household, most often with Lizzie, who aspired to be like her relatives who lived on the “Hill.”

Andrew’s daughters, Lizzie and Emma, were never close with their stepmother, who they always called her “Mrs. Borden.” Rarely did they take their meals with Andrew and Abby. As their father grew more prosperous, the girls began to worry that Abby’s family sought to gain access to their father’s money. Growing up, the household was religious, and the family regularly attended the Central Congregational Church, located in the influential neighborhood of the “Hill.” Lizzie was very involved in church activities and organizations and taught Sunday school. Emma and Lizzie helped their father manage his rental properties when they were old enough.

Emma rarely left the house and was described as “prim, confident, apparently reliable in every fiber.” However, Lizzie was more active and outgoing than her sister. She was described as having red hair and was attractive. She had several suitors and escorts, but most were not from the “Hill” neighborhood to which she aspired. Though the family attended the church of the town’s aristocracy, they didn’t really fit in, even though they had money. Andrew’s frugal ways and somewhat shady reputation as a businessman relegated the family to middle-class social status. Even if Lizzie would accept a suitor outside her aspirations, her father rejected them as “fortune hunters.” Both she and her sister were doomed to spinsterhood.

In the months prior to the murders, tension had been growing in the household, especially after Andrew made a real estate gift to Abby and her sister. Emma and Lizzie then demanded that they be granted a piece of real estate and were given the house they had lived in until their mother died. A few weeks later, they sold it back to their father for $5,000.

In May 1892, believing that the pigeons roosting in the barn were pests, Andrew killed them with a hatchet. Lizzie, who had recently built a roost for the birds, was very upset. A family argument in July 1892 prompted both sisters to take an extended “vacation” to New Bedford, Massachusetts. They returned a week before the murders, but Lizzie didn’t go straight home. Instead, she stayed in a local rooming house for four days before returning to the family residence.

For several days before the murders, the entire household had been violently ill. On August 3, Abby called for Dr. Seabury Bowen to visit and told him she feared poisoning. However, the doctor said it was probably due to bad food. He offered to take a look at the rest of the family, but Andrew, angry that Abby was wasting money on a doctor, ordered him to leave.

That evening, “Uncle John” Morse, the younger brother of Sarah Morse Borden, mother of Lizzie and Emma, visited the Borden residence unannounced. He had not been involved in the girls’ lives until about two years before the murders when he began showing up at the Borden house for “visits” of his nieces. He was allegedly there to discuss business matters with Andrew. Some writers have speculated that their conversation about property transfers may have aggravated the already tense situation. He spent the night in an upstairs bedroom.

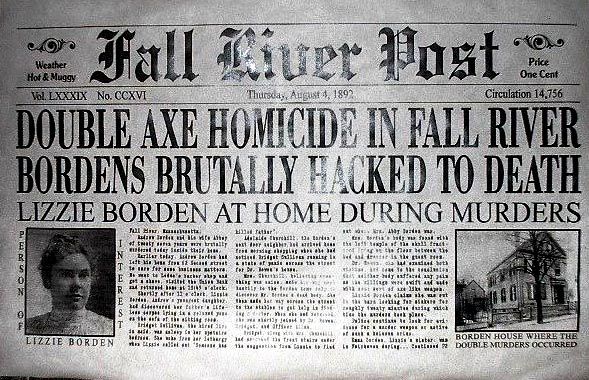

On the morning of August 4, 1892, Andrew and Abby Borden were found brutally murdered in their home. By this time, Lizzie was 32, and her sister Emma was 41. Both were spinsters and still lived with their father and stepmother. However, on the day of the murders, Emma Borden was out of town visiting a friend in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, about 15 miles away.

Lizzie was the first to find her father’s dead body. He had been bludgeoned to death while apparently sleeping on the sofa, and his face was almost beyond recognition. She screamed for the maid, Bridget Sullivan, who ran to fetch Dr. Bowen and a neighbor named Adelaide Churchill. Bridget Sullivan and Adelaide Churchill discovered Abby Borden in an upstairs guest bedroom. She was also dead, her head badly beaten. Death in both cases was caused by someone wielding a small, sharp hatchet.

The police were soon summoned to the scene who searched for evidence of an intruder and found none. They also looked for a murder weapon, and in the basement, they found two hatchets, two axes, and a hatchet head with a broken handle. The hatchet head was suspected of being the murder weapon as the break in the handle appeared fresh. Curiously, they didn’t find any blood anywhere except on the victims’ bodies.

The crime scene quickly became contaminated as it was filled with people other than the police, including journalists and curious neighbors. Further, the family was given much leeway in cleaning up the house. No one bothered to check Lizzie or Bridget for bloodstains and made only a cursory inspection of her room. The police were later criticized for their lack of diligence.

The authorities soon concluded that someone within the Borden home must have committed the murders. Because of her absence, Emma was ruled out, and they seemingly never focused on the maid, Bridget Sullivan. Their suspicions were then turned fully on Lizzie Borden.

In the meantime, Emma was notified of the deaths by Dr. Bowen, who sent her a telegram in Fairhaven urging her to return to Fall River.

Just two days after the murder, newspapers began reporting that there was evidence Lizzie Borden might have had something to do with her parents’ murders.

During the police investigation, Abby’s body was found cold, indicating that she was attacked first; the coroner estimated sometime between 9 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. She was struck in the head with a hatchet around 18 times. He further concluded that she was facing her killer at the time of the attack, but the first blow struck on the side of the head, causing her to turn and fall face down on the floor, at which time 17 more blows were directed at the back of her head.

Abby was 64 years old and weighed about 200 pounds at the time of her death. While some described her as a short, humorless soul who displayed little or no affection, others said she was kindly, generous, and eager to please.

Andrew’s body was still warm when the police arrived, indicating that he was killed after Abby. The coroner estimated the murder occurred between 10:30 a.m. and 11:10 a.m. He was struck in the face with a hatchet ten times.

Andrew was described as a tall, thin man, 70 years old, with hooded dark eyes and a long mean mouth.

In reconstructing the events of that morning, the investigation found that after breakfast, Andrew Borden and John Morse chatted in the sitting room for almost an hour. Afterward, Morse left at about 8:45, and Andrew left at about 9:00 to take a walk.

In the meantime, Bridget was washing windows, Abby was cleaning the guest room vacated by John Morse, and Lizzie was in the dining room ironing.

Mr. Borden returned home at about 10:30, and Lizzie discovered her father’s body at about 11:10.

Lizzie was arrested on August 11 and was represented by Andrew Jennings, who had long been an attorney for the Borden family. The next day, she entered a plea of “not guilty” and was transported to the Taunton, Massachusetts jail, eight miles north of Fall River.

The preliminary hearing occurred in Fall River from August 25 through September 1, 1892. A few months later, the grand jury heard the evidence between November 7-21. Lizzie was indicted for murder on December 2, 1892.

During this time, the newspapers were flooded with varying accounts of the affair. A story in the Boston Daily Globe reported rumors that “Lizzie and her stepmother never got along together peacefully, and that for a considerable time back they have not spoken.” However, the newspaper also noted that family members insisted relations between the two women were quite normal. The Boston Herald was kinder, reporting: “From the consensus of opinion, it can be said: In Lizzie Borden’s life there is not one unmaidenly nor a single deliberately unkind act.” Hundreds more stories appeared around the world describing the deaths in lurid detail and speculating on possible motives and even possible other perpetrators.

In the meantime, Lizzie was held in the Taunton, Massachusetts jail until her trial began in New Bedford, Massachusetts, on June 5, 1893. By the time the trial began, Lizzie had already become a media sensation.

During the investigation, inquest, and trial, several suspicious events were uncovered:

At her inquest, it was found that the day before the murders took place, Lizzie had tried to buy prussic acid, otherwise known as cyanide, from a drug store but was denied because a prescription was required. This testimony was suppressed during the trial.

Bridget Sullivan, the Borden’s maid

On the morning of the murders, Bridget Sullivan said that when Andrew returned from his walk at about 10:30, the lock was jammed, and she had to let him in. During this time, she testified that she had heard Lizzie laugh from the top of the stairs. However, Lizzie denied this.

Shortly after Andrew came home, he asked where Abby was, and Lizzie replied that she had received a note to visit a sick friend. However, neither a sick friend nor a note to Abby was ever located.

Lizzie also said that she had removed Andrew’s boots and helped him into his slippers before he lay down on the sofa for a nap. However, when the police found his body, he was wearing his shoes.

The front door and all the windows on the first floor had been locked; therefore, the only way to have entered the house was via the kitchen, but the women were in and out of there all morning. If someone had come in, how had he/she managed to commit two crimes and escape without attention.

During police questioning, Lizzie’s answers were confusing and contradictory, claiming to have been in various places during the murders. Further, she appeared both erratic and calm. This was explained away by having taken morphine to calm her nerves.

It seemed unlikely that Lizzie had not heard anything during the brutal crimes, though Lizzie claimed to have been in the barn loft at the time. The authorities were unconvinced because the barn loft revealed no footprints on the dusty floor, and the stifling heat in the loft would have discouraged anyone from being there that day.

It was also rumored that the victims’ Wills were missing. Andrew’s Will likely would have left much of his estate to his wife, who would leave little or nothing to Andrew’s daughters. Alternatively, if Abby died first, Andrew’s estate would automatically be left to his daughters.

During the trial, Lizzie’s attorney emphasized her close relationship with her father and the many church, charity, and volunteer efforts she was involved in. The prosecution, led by Hosea Knowlton, stressed the brutality of the crimes and Lizzie’s hatred for Abby.

Emma Borden strongly supported her sister during the trial and testified in her defense.

Borden did not take the stand in her own defense, and her inquest testimony was not admitted into evidence.

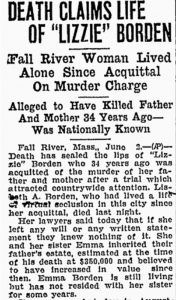

On June 20, 1893, after just 90 minutes of deliberation, Lizzie was acquitted of all charges due to a lack of forensic evidence linking her to the scene. Upon hearing the verdict, Lizzie let out a yelp of joy.

Not every newspaper was critical of her. After the verdict, the New York Times reported:

“It will be with a certain relief to every right-minded man or woman who has followed the case that the jury at New Bedford has not only acquitted Miss Lizzie Borden of the atrocious crime with which she was charged but has done so with a promptness that was very significant.”

No one else was ever investigated for the crime, and the case remains “officially” unsolved.

Many people, then and later, hypothesized as to how she could have escaped conviction. Some said it was because she was a sweet-looking Christian woman who wasn’t capable of murder. Others said she was so petite she wouldn’t have had the strength to kill someone. Some said there had been a reluctance to execute a female.

After acquittal, Lizzie returned to the family home and continued living with her sister, Emma.

However, rumors flew, and most people didn’t believe she was innocent; the newspapers and the public wouldn’t let the case go. Though she became a pariah in her own town, she chose to stay in Fall River, Massachusetts.

At the time of his death, 70-year-old Andrew Borden owned many properties around the Fall River area and had holdings in several prominent mills in the area. When his estate was settled, it was valued at $300,000, equivalent to over eight million dollars today.

After a considerable settlement was paid to settle claims by Abby’s family, Lizzie and Emma Borden inherited a significant portion of the estate, which allowed them to purchase a new home together.

Lizzie finally got her “Hill” house, which she named “Maplecroft” in 1893. The Queen Anne Victorian home was about 4,000 square feet with eight bedrooms, four bathrooms, and six fireplaces. Here, they hired live-in maids, a housekeeper, and a coachman.

Around this time, Lizzie began using the name Lizbeth. In her new influential neighborhood, Lizzie continued to attend the same church and hoped with her new-found wealth, she would finally fit into the elite upper-class society to which she had long aspired. However, friends and acquaintances soon stopped talking to her; she was no longer met with cordial greetings, and people began to avert their eyes.

Unfortunately, Lizzie made matters worse by never wearing mourning clothes and flaunting her wealth. She bought a new carriage that two beautiful horses pulled, purchased fashionable and expensive clothes, and traveled to Boston, New York, and Washington D.C., where she stayed in expensive hotels and indulged her love of the theater.

The newspapers were only too happy to obsess over her luxurious life. Further, the Fall River Globe, every year on the anniversary of the murders, printed an article about the crime, which always openly pointed at Lizzie Borden.

As the gossip continued, eggs were thrown at her house, churchgoers shunned her at services, and rope-skipping children maligned her with the sing-song verses of a popular, new rhyme: “Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother 40 whacks. When she saw what she had done, she gave her father 41.”

Her reputation was further tarnished when she was accused of shoplifting in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1897.

The sisters lived peacefully in the upscale neighborhood at Fall River until 1904, when Lizzie Borden met an actress named Nance O’Neill. The two formed a strong bond, with some even speculating that they were lovers. Emma disapproved of the friendship, and after Lizzie threw a party for O’Neil and her theatrical troupe at their home in 1905, Emma abruptly moved out.

It is unknown where Emma immediately went, but years later, in 1923, she was living in a nursing home in Newmarket, New Hampshire, where she had moved for health reasons and allegedly to avoid renewed publicity following the publication of another book about the murders.

Lizzie Borden continued to live in her house in the fashionable Fall River neighborhood and, at some point, replaced her carriage and horses with a fine limousine. She also continued to travel extensively. As she grew older, she became stout and matronly.

In 1926, she had her gallbladder removed and afterward was chronically ill. She died of pneumonia in Fall River, Massachusetts, on June 1, 1927. Funeral details were not published, and few attended. Her sister, Emma Borden, died of kidney problems nine days later, on June 10, 1927, in Newmarket, New Hampshire.

The sisters were buried beside their father in the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery.

After Lizzie’s death, she left $30,000 (equivalent to $422,500 in 2018) to the Fall River Animal Rescue League, $500 ($7,041 in 2018) in trust for perpetual care of her father’s grave, and her closest friend and a cousin each received $6,000 ($84,500 in 2018).

Many old mills can still be seen in Fall River, testimony to more prosperous times. The downtown area where Andrew once worked and lived is mainly gone, destroyed by fires, demolition, and the intrusion of Interstate I-95.

But the Borden murder house still stands at 92 Second Street (today 230 Second Street), serving as a Bed and Breakfast Inn and museum providing tours. Her “new” Hill house, located about a mile away, also continues in what is known today as the Highland District. It is a private residence.

Fall River is located about 50 miles south of Boston, Massachusetts.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See:

Sources:

Biography.com

Illinois State University

Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast

New York Times

Wikipedia