La Purisima Mission, Lompoc, California courtesy Wikipedia.

Misión La Purísima Concepción De María Santísima (Mission of the Immaculate Conception of Most Holy Mary) was founded by Father Presidente Fermin de Lasuén in December 1787 and was the 11th of 21 Franciscan Missions in California. Located in Lompoc, California, the Spanish mission today is part of the larger La Purísima Mission State Historic Park. Together with Mission San Francisco de Solano, it is one of only two of the Spanish missions in California that is no longer under the control of the Catholic Church.

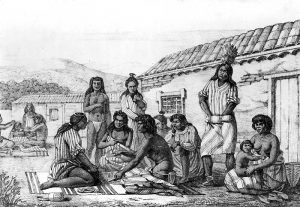

The Spanish established Franciscan Catholic missions throughout California during the 18th and early 19th centuries to colonize the Pacific coast region and spread their Christian faith to local American Indian tribes. The Spanish introduced a new religion to the native peoples; they also brought new livestock, fruit, vegetables, farming techniques, and social practices. The missions, which were not just churches, but entire settlements, completely changed life in California.

Father Presidente Fermin de Lasuén founded Misión La Purísima Concepción on December 8, 1787. The first friars assigned to La Purísima were Father Vincente Fuster and Father Joseph Arroita. The two padres organized the construction of temporary buildings at La Purísima and translated the mass and catechism instruction into the native tongue of the local Chumash Indians. Since the mission was more than just a church, construction began on living quarters, workshops, and storage and water systems. As the Spanish baptized the Chumash Indians, they taught them skills that enabled the Indians to help in the development of the mission.

A contemporary report provides some insights into the daily life of the Chumash Indian neophytes at the mission. In 1800, Father Horra, formerly at Mission San Miguel, accused the La Purísima Mission fathers of mistreating the Chumash Indians. Governor Borcia, the Spanish governor at the time, investigated, and the priests at La Purísima reported about the lives of the neophytes. They said the converts received three meals a day, had permission to gather their own wild foods, and had clothing expected to last one year. They lived in their native tule houses, for it was not possible to construct permanent houses for them. The Spanish required their labor for no more than five hours per day, taught the Indians how to deal with the soldiers and other people outside of the mission, and punished them if they left the mission without permission. Ultimately, Spanish officials declared the charges against the missionaries unfounded.

In the developmental years of the mission, the priests received help from the other missions in the form of livestock, vegetables, and cuttings to establish orchards and vineyards. Supplies the missions could not produce, including bells, church furnishings, cloth, tools, and iron, arrived on supply ships from New Spain (Mexico) two times a year. In addition, the Padres received a stipend and an allotment from the Pious Fund; a fund wealthy Spaniards supported with donations to help expand Spain’s empire.

The mission grew and prospered, and in a report dated December 31, 1798, La Purísima claimed that the mission’s primitive church did not have enough space for its 920 inhabitants. A new, larger, and permanent adobe church was constructed between 1801 and 1803 to accommodate the mission’s growing population.

La Purísima expanded to include several permanent large and small adobe buildings and had nearly 1,500 converts. The mission prospered under Father Mariano Payeras, who arrived in 1804. La Purísima began producing soap, candles, wool, leather, and other leading commodities to trade. The Padres also hired out the neophytes to local ranchos as an additional source of income for the mission. At the height of its prosperity, however, La Purísima faced a series of setbacks. Between 1804 and 1807, smallpox and measles struck, and nearly 500 Chumash Indians died. Then, on December 21, 1812, life at La Purísima changed suddenly when a severe earthquake, followed by torrential rains, damaged all of the buildings beyond repair. With their unprotected adobe bricks, the damaged buildings melted back into the mud.

Father Payeras requested and was granted permission to rebuild the mission four miles northwest in a small canyon closer to the El Camino Real, California’s main travel route. The Padres established La Purísima in its new location on April 23, 1813. Using materials salvaged from the buildings destroyed by the earthquake, construction began immediately. The new site departed from the traditional layout of the California missions, which included a settlement arranged around four sides with an open square. The new mission was constructed in a straight line at the base of a long hill. Completed within 10 years, La Purísima’s new buildings included the priests’ residence, storehouses, workshops, quarters for the soldiers, the mission church, the Indian infirmaries and dormitory, the blacksmith’s quarters, a pottery shop, and the Padres’ private kitchen. These buildings are part of the reconstructed La Purísima Mission State Park today.

In just a few short years, Father Payeras turned La Purísima into a thriving mission once again. About 1,000 Chumash Indian neophytes lived on mission lands. The mission became a school and training center for its inhabitants and a great ranching enterprise. While thousands of heads of livestock roamed the hills, the Padres developed shops for weaving, pottery, leatherwork, and other crafts. In 1815, the Catholic Church recognized Father Payeras for his talents and outstanding achievements and appointed him the presidente of the California missions. Father Payeras decided to remain at La Purísima during his time as presidente instead of moving to the Carmel Mission, which had been the standard practice at the time. In 1819, he received the appointment of commissary prefect, the highest rank among California Franciscans. Father Payeras died on April 28, 1823, and lies buried under the altar of La Purísima Mission.

Even though Father Payeras was a strong leader, La Purísima could not deny the turmoil unfolding throughout the region. By 1811, after the Hidalgo Rebellion in New Spain (which was the beginning of Mexico’s War for independence from Spain), supplies and money stopped coming to the missions. Spanish governors still clung to old Spanish policy and would not let the missions trade with foreign merchants—this created supply shortages, which led to black-market activity. Tensions grew between the soldiers, who were now dependent upon the mission, and the mission people. The soldiers took their frustrations out on the Indian neophytes.

By 1824, the increasing conflict between the soldiers and the Indians reached a breaking point. After hearing news that soldiers at Mission Santa Inez flogged a La Purísima neophyte, the Indian converts took control of the mission’s grounds. Father Ordaz and the soldiers and their families went to Mission Santa Inez, while Father Rodriguez could still come and go from La Purísima as he pleased. About a month after the rebellion, known as the Chumash Revolt, began, 109 soldiers from the Presidio of Monterey arrived to regain control of the mission. A violent fight that lasted only two and a half hours left 16 Indians dead and one soldier and two others wounded. Seven Indians suffered execution for their involvement in the rebellion, and 12 more were punished to hard labor.

La Purísima Mission never fully recovered after the rebellion, and by 1834, the Mexican officials enforced the order to secularize California’s missions. A civil administrator managed the grounds until Juan Temple of Los Angeles purchased La Purísima Mission for $1,000 in 1845. Ownership of La Purísima Mission subsequently changed hands multiple times until 1933, when its new owner, Union Oil Company, recognized the site’s historic value and donated it to the State of California.

However, after years of neglect and vandalism, the mission was in ruins. Utilizing records, photographs, interviews with early settlers, and archeological study, the mission began to be was completely restored in 1934 through the efforts of the County of Santa Barbara, the State of California, the National Park Service, and the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Today, the mission appears as it did in 1820. The state park features 10 of the reconstructed buildings, including the church, shops, living quarters, and blacksmith shop. These furnished buildings, mission gardens, livestock, living history events, the restored historic aqueduct, and its visitor center give visitors a glimpse into what life was like on a California mission. The mission was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970. A nominal entry fee is charged to each vehicle entering the state park.

More Information:

La Purísima Mission State Historic Park

2295 Purisima Road

Lompoc, California 93436

805-733-3713

Compiled by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2021.

Also See:

List of Missions & Presidios in the United States

Missions & Presidios of the United States

Spanish Missions & Presidios Photo Gallery

Source: National Park Service