The beautiful five-masted schooner, the Carroll A. Deering, had a short life, sailing for just a few years before she was found completely abandoned on the Diamond Shoals of North Carolina in 1922. The mystery of what happened remains one of maritime history’s most famous ghost ship stories.

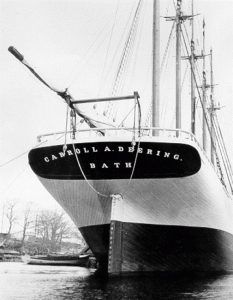

The Carroll A. Deering was built in Bath, Maine, in 1919 by the G.G. Deering Company for commercial use and was named for the owner’s son. The ship was 255 feet long, 44 feet wide, and weighed 1,879 tons. Designed to carry coal at a capacity of 3,500 tons, she was the largest and the last ship ever constructed by G. G. Deering Company and one of the last wooden cargo ships ever built.

She was first launched on April 4, 1919, in Bath, Maine, and after sailing for almost a year and a half, she was in excellent shape when she set sail from Norfolk, Virginia, on August 22, 1920, bound for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Onboard was an experienced captain, William H. Merritt. Merritt, a hero of World War I; his son, Sewall Merritt, who served as the first mate; a crew of ten men and a cargo hold filled with coal. However, just a few days later, Captain Merritt fell seriously ill, and the ship was turned back, landing at the port of Lewes, Delaware, where Merritt and his son disembarked. The Deering Company replaced the two with Captain Willis B. Wormell, a retired 66-year-old veteran sea captain, and Charles B. McLellan as the first mate. Once again, on September 8, 1920, the ship set sail and made its way to Brazil, delivering the coal without incident.

Captain Wormell then gave his crew some leave time, and while he was there, he visited another ship captain and old friend named George Goodwin. Wormell had expressed concern to Goodwin about the crew on Carroll A. Deering, stating that they were unruly and didn’t trust them, except the engineer, Herbert Bates.

On December 2, 1920, the Deering left Brazil and went to Bridgetown, Barbados, where it stopped for supplies. While there, Captain Willis Wormell spoke with Captain Hugh Norton of the Augustus W. Snow and told him that he was having trouble with the crew — especially first mate Charles B. McLellan, stating that he was “habitually drunk while ashore” and mistreated the crew.

While they were there, first mate McLellan got drunk and complained to Captain Norton that he could not discipline the crew without Captain Wormell interfering. He had to do all the navigation owing to Wormell’s poor eyesight. Later, Captain Norton, his first mate, and another captain heard McLellan say, “I’ll get the captain before we get to Norfolk; I will.” At some point, due to his drunkenness, McLellan was arrested. However, Captain Wormell bailed him out of jail on January 9, 1921, and the Deering immediately set sail for Hampton Roads, Virginia.

Schooner Carroll A. Deering, seen from the Cape Lookout lightship on January 28, 1921, by the U.S. Coast Guard.

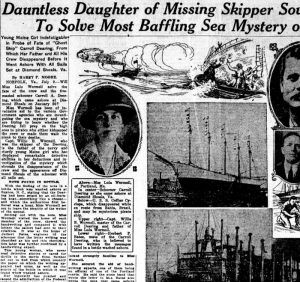

On January 29, 1921, the Deering passed by the Cape Lookout lightship off North Carolina and hailed it, reporting having lost both anchors and chains in a storm off Cape Fear. The man also asked that the ship’s owner, the G.G. Deering Company, be notified. However, the lightship’s keeper, Captain Thomas Jacobson, could not convey the message because his radio was out. Captain Jacobson would later say that the man who hailed the lightship was a tall thin man with reddish hair speaking through a megaphone. He also stated that the man didn’t act or speak like an officer as his speech was broken, and Jacobson took him for Scandinavian. Jacobson also noticed that the crew was “milling around” on the ship’s quarterdeck, where they were usually not allowed. The next day, the crew of another vessel reported seeing the Deering sailing a course directly onto the Diamond Shoals.

In the early morning of January 31, the Deering was sighted by C.P. Brady, who was on lookout duty at the Cape Hatteras Coast Guard station. The vessel had run aground with all sails set on the outer edge of Diamond Shoals. Brady reported his findings, but rescue ships could not approach the Deering due to bad weather.

It wasn’t until February 4 that the ship could be boarded when a tugboat rescue crew led by Captain James Carlson went upon the Deering. The ship had been so battered it was taking on water. The crew found the vessel completely abandoned, and much of the equipment had been damaged. The steering equipment was disabled, the wheel had been shattered, the rudder disengaged from its stock, and the binnacle box staved in and broken. A sledgehammer leaned ominously nearby. The ship’s log and navigation equipment, the crew’s personal effects, life rafts, and the ship’s two lifeboats were missing from the vessel. The ladder was hanging over the side. Ironically, the galley looked as if food was being prepared when the vessel was abandoned. There were ribs in a pan, pea soup in a pot, and coffee on the stove.

Afterward, the ship was unsalvageable, pulled out into the ocean, and dynamited. Some of the ship’s wreckage washed ashore on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, where it remained visible for more than 30 years.

The U.S. government immediately launched an extensive investigation that lasted until late 1922, but an official finding was never made on the incident.

The weather was considered, especially hurricanes. Though powerful hurricanes were known to have been raging in the Atlantic, the Deering was moving away from them. The state of the ship indicated an orderly rather than panicked evacuation.

Piracy was considered, and some believed this was the cause, but no evidence was found to support this theory. Rum Runners were also suspected, as the crew’s disappearance occurred during Prohibition. This idea was primarily ruled out because the vessel was too large, conspicuous, and slow.

Many suspected it was a case of mutiny due to Wormell’s known conflict with his first mate. This idea is supported by the red-haired man who hailed the Cape Lookout lightship, which was certainly not the captain. Senator Frederick Hale of Maine advocated this theory, stating it was “a plain case of mutiny.” Despite some evidence that this might have been the case, nothing definitive has ever been proven.

It is also possible that once the Deering ran aground, the crew abandoned the ship, took refuge in the lifeboats, and were swept out to sea. It is also possible that the crew of the Deering was rescued by another ship in the area, the SS Hewitt, which was also lost with all hands at about the same time.

In the end, no sign or wreckage of the lifeboats was ever found. Nor were any members of the crew or their bodies. Speculation as to the vanishing of the ship’s crew continues to this day.

A few remaining pieces of the Carroll A. Deering, including her bell and capstan, are on display at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Disappearances & Mysterious Deaths

Legends, Ghosts, Myths & Mysteries

Sources:

Historical Blindness

Simpson, Bland; Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals: The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering, UNC Press, 2005

Southern Living

Wikipedia