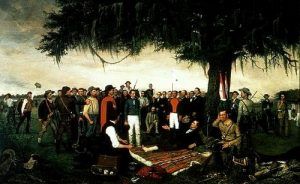

The Texas Revolution Ends after the Battle of San Jacinto

When Texas became a republic in 1836, after a long and bloody fight with Mexico, its independence was never recognized by the government of Mexico. It wouldn’t be until the United States annexed Texas in 1845 and the Mexican-American War of 1846-48 that the Mexicans would finally accept defeat. During the nine years between the revolution and annexation, the Republic of Texas teetered between collapse and continued threats of a Mexican invasion.

One tactic the Mexican government utilized was inciting the Native Americans to war with the republic. The Mexicans focused their efforts on the Cherokee of East Texas. The Cherokee had been migrating to Texas as early as 1807, and with the United States Indian removal policy of 1830, their numbers increased dramatically.

The Mexicans welcomed the Cherokee, seeing their presence as a buffer against emigrating Americans, and began negotiations to make permanent land grants to them in the early 1820s. Though the Mexican government made no land grants to the Indians, their promises lingered and appeared to have more potential for permanency than did the flood of encroaching white settlers, who promised them nothing.

When the Anglo-Texans began to protest Mexican rule in 1832, and the Texas Revolution erupted in 1835, the Cherokee, who had still not obtained title to their lands from Mexico, declared themselves neutral. However, many of them remained loyal to Mexican rule.

When Texas won its war with Mexico, Sam Houston promised to establish a reservation for the Cherokee in East Texas and began treaty negotiations. Though the agreement substantially reduced the Cherokee landholdings, the Cherokee agreed, believing it finally gave them a permanent home. Though the treaty was signed in 1836, it was never ratified by the Texas government.

In the meantime, the Mexican government saw the East Texas Cherokee as prime targets for revolt. It focused its persuasion efforts on militant factions of the tribe that remained pro-Mexican. Promising them both land and money, they soon began to incite some of the renegade factions of the Cherokee to drive the white settlers from the country. In 1838, several attacks were made on settlers in East Texas which were blamed on a combined Cherokee-Mexican force.

This muddied the waters for the pending treaty and greatly complicated Texan-Cherokee relations. Though Sam Houston attempted to preserve the peace before leaving office by establishing a boundary line separating the Cherokee territory, this only angered the Anglo-Texans who were clamoring for land and saw the Cherokee as allies of their enemies, the Mexicans.

Houston’s successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, inaugurated in 1839, quickly announced a policy favoring the total removal of “Sam Houston’s pet Indians” and sent the Texas Army to drive the Cherokee out by force. However, Cherokee Chief Duwali blocked the advance of the Texans. To this, Lamar notified Duwali that his people would be moved beyond the Red River “peaceably if they would; forcibly if they must.” The Cherokee decided to fight, which became known as the Cherokee War.

On July 15 and 16, 1839, a force of several hundred warriors led by Duwali met Texas forces in the Battle of the Neches near present-day Tyler, Texas. More than 100 Indians, including Chiefs Duwali and Bowles, were killed, and the remaining Cherokee were driven across the Red River into Indian Territory (Oklahoma.) Chief Bowles, an aged Cherokee leader, carried a sword given to him by Sam Houston.

As the Cherokee retreated, they were accompanied by the Mexicans, who still carried most of the money promised to them in return for driving out the white settlers.

The Indians’ retreat carried them through present-day Upshur County, where many scattered into the swamps and underbrush along what is now known as Little Cypress Creek, north of the present city of Gilmer. In the meantime, the Mexicans, fearing for their lives, were eager to offload the heavy gold and silver coins they carried, which made a quick escape impossible. According to the legend, the Mexicans hid their cache deep in Little Cypress Creek.

In no time, word of the hidden treasure spread, bringing dozens of people trying to find the hidden cache. One such story tells of two Irishmen, who, searching during the summer dry season, found two enclosed vessels at different locations in the Creek, but failed to locate the silver or gold.

Many believe that the treasure continues to lay beneath the mud of Little Cypress Creek in Upshur County.

As to the Cherokee, the Battle of the Neches ended the Indian troubles in east Texas, as the vast majority of the tribe had moved into Indian Territory. A few renegades continued to live a fugitive existence in Texas and even continued to fight against the Texans, but they had little success. Others took up permanent residence in Mexico.

When Houston was elected to a second presidential term in 1841, he inaugurated an Indian policy calculated to forestall future hostilities with immigrant tribes. As a result of his peace policy, treaties were concluded with the remaining Texas Cherokee in 1843 and 1844.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Also See: