Victoria Claflin Woodhull was a suffragist, feminist, and writer who was the first woman to run for President and the center of a national scandal.

She was born in Homer, Ohio, on September 23, 1838, and was one of several children whose parents ran a traveling medicine show, doing faith healings, telling fortunes, and selling medicines. She received no formal education and was self-taught.

When she was just 15, she married 28-year-old Canning Woodhull, who practiced as a doctor when medical education and licensing were not required in Ohio. She soon learned that her new husband was an alcoholic and womanizer who often didn’t work. Though the couple had two children, she divorced him in 1864, a time when “divorce” itself was a scandal. A couple of years later, Victoria remarried Colonel James Blood, and in 1868, the pair, along with her younger sister, Tennessee “Tennie” Claflin, moved to New York City.

Victoria and Tennie soon set out to make their fortunes, and the pair became the first female Wall Street brokers in 1870. With the help of a wealthy benefactor, her admirer Cornelius Vanderbilt, Woodhull, Claflin & Company began, and the two women were hailed as “the Queens of Finance.”

The sisters also established a newspaper called Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly the same year, which published controversial opinions advocating women’s suffrage, short skirts, spiritualism, free love, sex education, and licensed prostitution. Widely criticized for promiscuity, she answered these charges in her newspaper.

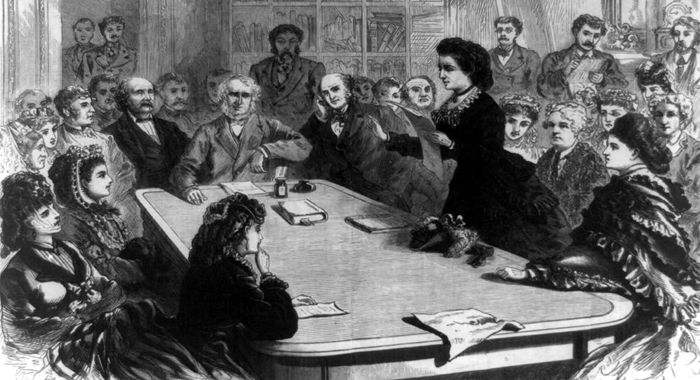

Due to her radical views, she was not accepted by many known suffragists of the time, such as Susan B. Anthony. Still, in 1872, she was nominated for the U.S. presidency at the New York Convention of a minor Equal Rights Party, running against incumbent Ulysses S. Grant. Although laws prohibited women from voting at the time, no laws stopped women from running for office. She wasn’t a threat, but she did have the fame of being the first woman to run for the job.

Friends of President Ulysses Grant decided to attack her character, and she was accused of having affairs with married men; her first husband’s alcoholism was brought up, and they said one of her sisters was a drug addict. Fighting back, Victoria was convinced that a popular minister of the time, Henry Ward Beecher, was behind the attacks. She published a story in her newspaper that the minister was having an affair with a friend’s wife. A member of the Plymouth Church, Theodore Tilton, disclosed to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a colleague of Woodhull, that his wife had confessed to having an affair with Beecher. Provoked by the hypocrisy, Woodhull exposed Beecher, setting off a national scandal.

On November 2, 1872, just days before the presidential election, Victoria, her husband, James Blood, and her sister, Tennie, were arrested for sending obscene material through the mail. Held for the next month, she was in jail on election day, and her name did not appear on the ballot because she was one year short of the mandated age of 35.

Over the next seven months, Woodhull was arrested eight times and had to go through several trials for obscenity and libel. She was eventually acquitted of all charges, but the legal bills forced her into bankruptcy. Though highly controversial, her newspaper was published for six years, finally ceasing to exist in 1876. That same year, she obtained her second divorce from James Blood.

In the meantime, the Reverend Beecher stood trial in 1875 for adultery, which was splashed across newspapers nationwide. The trial ended in a hung jury, which an outraged Elizabeth Stanton called a “holocaust of womanhood.”

Woodhull tried to secure nominations for the presidency again in 1884 and 1892 but was unsuccessful. She eventually married an English banker named John Biddulph Martin, and they left the United States for England in 1878. There, she continued campaigning for women’s rights and, in 1892, established the Humanitarian newspaper, which lasted until 1901. She died on June 9, 1927.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See: