By Marie L. McLaughlin

There once lived a chief’s daughter who had many relations. All the young men in the village wanted to have her for their wife and were all eager to fill her skin bucket when she went to the brook for water.

There was a young man in the village who was industrious and a good hunter but poor and from a mean family. He loved the maiden, and when she went for water, he threw his robe over her head while he whispered in her ear:

“Be my wife. I have little, but I am young and strong. I will treat you well, for I love you.”

For a long time, the maiden did not answer, but one day she whispered back.

“Yes, you may ask my father’s leave to marry me. But first, you must do something noble. I belong to a great family and have many relations. You must go on a war party and bring back the scalp of an enemy.”

The young man answered modestly, “I will try to do as you bid me. I am only a hunter, not a warrior. Whether I shall be brave or not, I do not know. But I will try to take a scalp for your sake.”

So he made a war party of seven, himself and six other young men. They wandered through the enemy’s country, hoping to get a chance to strike a blow. But none came, for they found no one of the enemies.

“Our medicine is unfavorable,” said their leader at last. “We shall have to return home.”

Before they started, they sat down to smoke and rested beside a beautiful lake at the foot of a green knoll that rose from its shore. The knoll was covered with green grass, and somehow as they looked at it, they felt that something about it was mysterious or uncanny.

But there was a young man in the party named the jester, for he was venturesome and full of fun. Gazing at the knoll, he said: “Let’s run and jump on its top.”

“No,” said the young lover, “it looks mysterious. Sit still and finish your smoke.”

“Oh, come on, who’s afraid,” said the jester, laughing. “Come on you–come on!” and springing to his feet, he ran up the side of the knoll.

Four of the young men followed. Having reached the top of the knoll, all five began to jump and stamp about in sport, calling, “Come on, come on,” to the others. Suddenly they stopped—the knoll had begun to move toward the water. It was a gigantic turtle. The five men cried out in alarm and tried to run—too late! Their feet, by some power, were held fast to the monster’s back.

“Help us–drag us away,” they cried; but the others could do nothing. In a few moments, the waves had closed over them.

The other two men, the lover and his friend, went on with heavy hearts, for they had forebodings of evil. After some days, they came to a river. Worn with fatigue, the lover threw himself down on the bank.

“I will sleep awhile,” he said, “for I am wearied and worn out.”

“And I will go down to the water and see if I can chance upon a dead fish. At this time of the year, the high water may have left one stranded on the seashore,” said his friend.

And as he said, he found a fish he cleaned and then called to the lover.

“Come and eat the fish with me. I have cleaned it and made a fire, which is now cooking.”

“No, you eat it; let me rest,” said the lover.

“Oh, come on.”

“No, let me rest.”

“But you are my friend. I will not eat unless you share it with me.”

“Very well,” said the lover, “I will eat the fish with you, but you must first make me a promise. If I eat the fish, you must promise, pledge yourself, to fetch me all the water that I can drink.”

“I promise,” said the other, and the two ate the fish out of their war kettle. For there had been but one kettle for the party.

When they had eaten, the kettle was rinsed out, and the lover’s friend brought it back full of water. This the lover drank at a draught.

“Bring me more,” he said.

Again his friend filled the kettle at the river, and again the lover drank it dry.

“More!” he cried.

“Oh, I am tired. Cannot you go to the river and drink your fill from the stream?” asked his friend.

“Remember your promise.”

“Yes, but I am weary. Go now and drink.”

“Ek-hey, I feared it would be so. Now trouble is coming upon us,” said the lover sadly. He walked to the river, sprang in, and drank greedily, lying down in the water with his head toward land. By and by he called his friend.

“Come hither, you who have been my sworn friend. See what comes of your broken promise.”

The friend came and was amazed to see that the lover was now a fish from his feet to his middle.

Sick at heart, he ran off a little way and threw himself upon the ground in grief. By and by, he returned. The lover was now a fish to his neck.

“Cannot I cut off the part and restore you by a sweat bath?” the friend asked.

“No, it is too late. But tell the chief’s daughter that I loved her to the last and that I die for her sake. Take this belt and give it to her. She gave it to me as a pledge of her love for me,” and he is then turned to a great fish, swam to the middle of the river, and there remained, only his great fin remaining above the water.

The friend went home and told his story. There was great mourning over the death of the five young men and for the lost lover. In the river, the great fish remained its fin just above the surface and was called by the Indians “Fish that Bars” because it bar’d navigation. Canoes had to be portaged at great labor around the obstruction.

The chief’s daughter mourned for her lover as for a husband, nor would she be comforted. “He was lost for love of me, and I shall remain as his widow,” she wailed.

In her mother’s teepee, she sat, with her head covered with her robe, silent, working, working. “What is my daughter doing,” her mother asked. But the maiden did not reply.

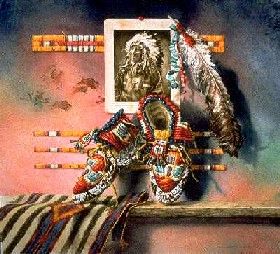

The days lengthened into moons until a year had passed. And then the maiden arose. In her hands were beautiful articles of clothing, enough for three men. There were three pairs of moccasins, three pairs of leggings, three belts, three shirts, three headdresses with beautiful feathers, and sweet-smelling tobacco.

“Make a new canoe of bark,” she said, which was made for her.

Into the canoe, she stepped and floated slowly down the river toward the great fish.

“Come back, my daughter,” her mother cried in agony. “Come back. The great fish will eat you.”

She answered nothing. Her canoe came to the place where the great fin arose and stopped, its prow grating on the monster’s back. The maiden stepped out boldly. One by one, she laid her presents on the fish’s back, scattering the feathers and tobacco over his broad spine.

She answered nothing. Her canoe came to the place where the great fin arose and stopped, its prow grating on the monster’s back. The maiden stepped out boldly. One by one, she laid her presents on the fish’s back, scattering the feathers and tobacco over his broad spine.

“Oh, fish,” she cried, “Oh, fish, you who were my lover, I shall not forget you. Because you were lost for the love of me, I shall never marry. All my life, I shall remain a widow. Take these presents. And now leave the river, and let the waters run free, so my people may once more descend in their canoes.”

She stepped into her canoe and waited. Slowly the great fish sank, his broad fin disappeared, and the waters of the St. Croix (Stillwater) were free.

By Marie L. McLaughlin, 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

About the Author: Myths and Legends of the Sioux was written by Marie L. McLaughlin in 1913. The text as it appears here, however, is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader. McLaughlin, who was of ¼ Sioux blood and was born and reared in the Indian community, acquired a thorough knowledge of the Sioux people and language at an early age. While living on an Indian reservation for more than forty years, she learned the legends and folklore of the Sioux. These legends and myths were told in the lodges, at the past campfires, and then later by the firesides of the Dakota. McLaughlin kept careful notes of the many tales told to her by the Sioux elders until she published this book of legends in 1913.

Also See:

Legends, Ghosts, Myths & Mysteries