By William Worthington Fowler in 1877

Of all the tens of thousands of devoted women who have accompanied the grand army of pioneers into the wilderness, not but one has been either a soldier to fight, a laborer to toil, or a ministering angel to soothe the pains and relieve the sore wants of her companions. She has seldom acted worthily in all these several capacities, fighting, toiling, and ministering by turns. If each of these brave and faithful women had kept a diary of the events of their pioneer lives, what a record of toil, warfare, and suffering it would present. How many different types of female characters in different spheres of action would it show — the self-sacrificing mother, the tender and devoted wife, the benevolent matron, the heroine who blenched not in battle! Unnumbered thousands have passed beautiful, strenuous, and brave lives far from the scenes of civilization and gone down to their graves, leaving only local, feeble voices, if any, to celebrate their praises. Today, we do not know the place of their burial. Others have had their memories embalmed by the pens of faithful biographers, and a few also have left diaries containing a record of the wonderful vicissitudes of their lives.

A woman’s life experience in the wilderness is never better told than in her own words. More impressible than a man to passing events, more susceptible to pain and pleasure, enjoying and sorrowing more keenly than her sterner and rougher mate, she often possesses a peculiarly graphic power in expressing her own thoughts and feelings and also in delineating the scenes through which she passes.

Therefore, a woman’s diary of frontier life possesses an intrinsic value because it is a faithful story and, at the same time, one of surpassing interest as a consequence of her personal and active participation in the toils, sufferings, and dangerous incidents of such a life.

Mrs. Williamson of Pennsylvania

Such a diary is that of Mrs. Williamson, which, in the quaint style of the olden times, relates her thrilling experience in the wilds of Pennsylvania. We see her first as an affectionate, motherless girl accompanying her father to the frontier, assisting him in preparing a home for his old age in the depths of the forest and enduring with cheerful resolution the manifold hardships and trials of pioneer life, and finally closing her aged parent’s eyes in death. Then we see her as a wife, the partner of her husband’s cares and labors, and as a mother, the faithful guardian of her sons; and again as a widow, her husband having been torn from her arms and butchered by a band of ruthless Indians. After her sons had grown to be sturdy men and had left her to make homes for themselves, she showed herself to be the strong and self-reliant matron of 50, still keeping her outpost on the border and cultivating her clearing with the assistance of two black men. At last, after a life of toil and danger, she is attacked by a band of Indians and defends her home so bravely that after making her their captive, they spare her life and, in admiration of her courage, adopt her into their tribe. She dissembles her reluctance, humors her Indian captors, and forces herself to accompany them on their bloody expeditions, wherein she saves many lives and mitigates the sufferings of her fellow captives.

The narrative of the escape is given in her own quaint words:

“One night, the Indians, greatly fatigued with their day’s excursion, composed themselves to rest as usual. Observing them to be asleep, I tried various ways to see whether it was a scheme to prove my intentions or not, but after making a noise and walking about, sometimes touching them with my feet, I found there was no fallacy. My heart then exulted with joy at seeing a time come that I might, in all probability, be delivered from my captivity, but this joy was soon dampened by the dread of being discovered by them or taken by any straggling parties, to prevent which, I resolved, if possible, to get one of their guns, and, if discovered, to die in my defense, rather than be taken. For that purpose, I tried to get one from under their heads (where they always secured them), but in vain.

“Frustrated in this my first essay towards regaining my liberty, I dreaded the thought of carrying my design into execution: yet, after a little consideration, and trusting myself to the divine protection, I set forward, naked and defenseless as I was; a rash and dangerous enterprise! Such was my terror, however, that in going from them, I halted and paused every four or five yards, looking fearfully toward the spot where I had left them, lest they should awake and miss me, but when I was about two hundred yards from them, I mended my pace, and made as much haste as I could to the foot of the mountains; when on sudden I was struck with the greatest terror and amaze, at hearing the wood-cry, as it is called, they make when any accident happens them. However, fear hastened my steps, and though they dispersed, not one happened to hit upon the track I had taken. When I had run nearly five miles, I met with a hollow tree, in which I concealed myself till the evening of the next day when I renewed my flight, and next night slept in a canebrake. The following day I crossed a brook and got more leisurely along, retiming thanks to Providence, in my heart, for my happy escape, and praying for future protection. On the third day, in the morning, I perceived two Indians armed, at a short distance, which I certainly believed were in pursuit of me by their alternately climbing into the highest trees, no doubt to look over the country to discover me.

This retarded my flight for that day; but at night I resumed my travels, frightened and trembling at every bush I passed, thinking each shrub that I touched, a savage concealed to take me. It was moonlight nights till near morning, which favored my escape. But how shall I describe the fear, terror, and shock that I felt on the fourth night, when, by the rustling, I made among the leaves, a party of Indians that lay around a small fire, nearly out, which I did not perceive, started from the ground, and seizing their arms, ran from the fire into the woods. Whether to move forward or to rest where I was, I knew not, so distracted was my imagination. In this melancholy state, revolving in my thoughts the now inevitable fate I thought waited on me, to my great astonishment and joy, I was relieved by a parcel of swine that made it towards the place where I guessed the savages to be; who, on seeing the hogs, conjectured that they had occasioned their alarm, and directly returned to the fire, and lay down to sleep as before. As soon as I perceived my enemies so disposed of, with more cautious steps and silent tread, I pursued my course, sweating (though the air was frigid) with the fear I had just been relieved from. Bruised, cut, mangled, and terrified as I was, I still, through divine assistance, was enabled to pursue my journey until the break of day, when, thinking myself far off from any of those miscreants I so much dreaded, I lay down under a great log, and slept undisturbed until about noon, when, getting up, I reached the summit of a great hill with some difficulty; and looking out if I could spy any inhabitants of white people, to my unutterable joy I saw some, which I guessed to be about ten miles distance. This pleasure was diminished by my inability to get among them that night; therefore, when evening approached, I again recommended myself to the Almighty and composed my weary, mangled limbs to rest. In the morning, I continued my journey towards the nearest cleared lands I had seen the day before and about four o’clock in the afternoon; I arrived at the house of John Bell.”

Mrs. Daviess of Kentucky

Mrs. Daviess was another of these women who, like Mrs. Williamson, was a born heroine, of whom many acted a conspicuous part in the territorial history of Kentucky. Large and splendidly formed, she possessed the strength of a man with the gentle loveliness of the true woman. In the hour of peril, and such hours were frequent with her, she was firm, cool, and fertile of resource; her whole life, of which we give only a few episodes, was one continuous succession of brave and noble deeds. Both she and Mrs. Williamson appear to have been actual instances of the poet’s ideal:

“A perfect woman nobly planned

To warn, to comfort, and command.”

Her husband, Samuel Daviess, was an early settler at Gilmer’s Lick in Lincoln County, Kentucky. In August 1782, while a few rods from his house, he was attacked early one morning by an Indian, and attempting to get within doors, he found that the other Indians had already occupied his house. He succeeded in making his escape to his brother’s station, five miles off, and giving the alarm, he was soon on his way back to his cabin in company with five stout, well-armed men.

Meanwhile, the Indians, four in number, who had entered the house while the fifth was in pursuit of Mr. Daviess, roused Mrs. Daviess and the children from their beds and gave them to understand that they must go with them as prisoners. Mrs. Daviess occupied as long a time as possible in dressing, hoping that some relief would come. She also delayed the Indians nearly two hours by showing them one article of clothing and then another, explaining their uses and expatiating their value.

While this was going on, the Indian who had been in pursuit of her husband returned with his hands stained with pokeberries, waving his tomahawk with violent gestures as if to convey the belief that he had killed Mr. Daviess. The keen-eyed wife soon discovered the deception and was satisfied that her husband had escaped uninjured.

After plundering the house, the Indians started to depart, taking Mrs. Daviess and her seven children with them. Some of the children were too young to travel as rapidly as the Indians wished, and discovering, as she believed, their intention to kill them, she made the two oldest boys carry the two youngest on their backs.

To leave not rail behind them, the Indians traveled with the greatest caution, not permitting their captives to break a twig or weed as they passed along, and to expedite Mrs. Daviess’ movements, one of them reached down and cut off with his knife a few inches of her dress.

Mrs. Daviess was accustomed to handling a gun and was a good shot, like many other women on the frontier. She contemplated as a last resort that, if not rescued in the day, when night came, and the Indians had fallen asleep, she would deliver herself and her children by killing as many of the Indians as she could, believing that in a night attack, the rest would fly panic-stricken.

Mr. Daviess and his companions reached the house and, finding it empty, succeeded in striking the trail of the Indians and hastened in pursuit. They had gone but a few miles before they overtook them. Two Indian spies in the rear first discovered the pursuers and, running on, overtook the others and knocked down and scalped the oldest boy but did not kill him. The pursuers fired at the Indians but missed. The latter became alarmed and confused, and Mrs. Daviess, taking advantage of this circumstance, jumped into a skink hole with her infant in her arms. The Indians fled, and every child was saved.

In its early days, like most new countries, Kentucky was occasionally troubled with men of abandoned character, who lived by stealing the property of others and, after committing their depredations, retired to their hiding places, thereby eluding the operation of the law. One of these marauders, a man of desperate character who had committed extensive thefts from Mr. Daviess and his neighbors, was pursued by Daviess and a party whose property he had taken to bring him to justice.

While the party was in pursuit, the suspected individual, not knowing that anyone was pursuing him, came to the house of Daviess, armed with his gun and tomahawk, — no person being at home but Mrs. Daviess and her children. After he had stepped into the house, Mrs. Daviess asked him if he would drink something and, having set a bottle of whiskey on the table, requested him to help himself. Not suspecting any danger, the fellow set his gun by the door. While he was drinking, Mrs. Daviess picked it up and, placing herself in the doorway, had the weapon cocked and leveled upon him by the time he turned around and in a peremptory manner, ordered him to take a seat or she would shoot him. Struck with terror and alarm, he asked what he had done. She told him he had stolen her husband’s property and that she intended to take care of him herself. In that condition, she held him prisoner until the party of men returned and took him into their possession.

These are only a few similar acts that show Mrs. Daviess’s character. She became noted all through the frontier settlements of that region during the troublous times in which she lived, not only for her courage and daring but for her trickery in circumventing the stratagems of the wily Indians by whom her family was surrounded. Her oldest boy inherited his mother’s character and promised to be one of the most famous Indian fighters of his day when he met his death at the hands of his Indian foes in early manhood.

Suppose Mrs. Williamson and Mrs. Daviess were representative women in the more stormy and rugged scenes of frontier life. In that case, Mrs. Elizabeth Estaugh may stand as a true type of gentle and benevolent matron, brightening her forest home with her kindly presence and making her influence felt in a thousand ways for good among her neighbors in the lonely hamlet where she chose to live.

Mrs. Haddon Estaugh of Pennsylvania

Her maiden name was Haddon; she was the oldest daughter of a wealthy, well-educated, humble-minded Quaker of London. Nature endowed her with strength of mind, earnestness, energy, and a heart overflowing with kindness and warmth of feeling. After the manner of her sect, the education bestowed upon her was highly practical, such as might be expected to draw forth her native powers by careful training of the mind without quenching the kindly emotions by which she was distinguished from her early childhood.

At the age of 17, she made a profession of religion, uniting herself with the Quakers. During her girlhood, William Penn visited her father’s house and greatly interested her by describing his adventures with the Indians in the wilds of Pennsylvania.

From that hour, her thoughts were directed towards the new world, where so many of her sect had emigrated, and she longed to cross the ocean and take up her abode among them. She pictured to herself the toils and privations of the Quaker pioneers in that new country. She ardently desired to join them, share their labors and dangers, and alleviate their sufferings by charitably dispensing a portion of that wealth she was destined to possess.

Her father sympathized with her views and aims and was at length induced to buy a large tract of land in New Jersey, where he proposed to go and settle in company with his daughter Elizabeth and carry out the plans she had formed there. His affairs in England took such a turn that he decided to remain in his native land.

This was a sad disappointment to Elizabeth. She had arrived at the conviction that among her people in the new world was to be her sphere of duty; she felt a call thither which she could not disregard, and when her father, who was unwilling that the property should lie unimproved, offered the tract of land in New Jersey to any relative who would settle upon it, she gladly availed herself of the proffer. She begged that she might go herself as a pioneer into that far-off wilderness.

It was a sore trial for her parents to part with their beloved daughter. Still, her character was so stable, and her convictions of duty so unswerving, that at the end of three months and after much prayer, they consented tearfully that Elizabeth should join “the Lord’s people in the new world.”

Arrangements were accordingly made for her departure, and all that wealth could provide or thoughtful affection devise was prepared for the long voyage across that stormy sea and against the hardships and trials in the forest home that was hers. In the spring of 1700, she set sail, accompanied by a poor widow of good sense and discretion, who had been chosen as her friend and housekeeper and two trustworthy men-servants, members of the Society of Friends.

Among the many extraordinary manifestations of strong faith and religious zeal connected with the early settlement of this country, few are more remarkable than this enterprise of Elizabeth Estaugh. Tenderly reared in a delightful home in a great city, where she had been surrounded with pleasing associations from infancy and where, as a lovely young lady, she was the idol of the circle of society in which she moved, she was still willing and desirous at the call of religious duty, to separate herself from home, friends, and the pleasures of civilization, and depart to a distant clime and a wild country. Hardly less remarkable and admirable was the self-sacrificing spirit of her parents in giving up their child in obedience to the promptings of her own conscience. We can imagine the parting on the vessel’s deck, spreading its sails to bear this sweet missionary away from her native land and the beloved of her old home. Angelic love beams and sorrow darkles from the serene countenances of the father, mother, and daughter, yet no tear is shed on either side. The vessel drops down the harbor, and the family stands on the pier, straining their eyes to catch the last look from the departing maiden, who leans on the bulwark and answers the silent and sorrowful faces with a heavenly smile of love and pity. Even during the long and tedious voyage, Elizabeth never wept. Her sense of duty controlled every other emotion of her soul, and she maintained her martyr-like cheerfulness and serenity to the end.

That part of New Jersey where the Haddon tract lay was, at that period, an almost unbroken wilderness. Scarcely more than 20 years had then elapsed since the 20 or 30 cabins had been built, which formed the germ settlement out of which grew the city of Brotherly Love, and nine miles of dense forest and a broad river separated the maiden and her household from the people in the hamlet across the Delaware River.

The home prepared for her reception stood in a forest clearing, three miles from any other dwelling. She arrived in June when the landscape was smiling in youthful beauty, and it seemed to her as if the arch of heaven was never so clear and bright, the carpet of the earth never so verdant. As she sat at her window and saw evening close in upon her in that broad forest home and heard for the first time the mournful notes of the whippoorwill and the harsh scream of the jay in the distant woods, she was oppressed with a sense of vastness, of infinity, which she never before experienced, not even on the ocean. She remained long in prayer, and when she lay down to sleep beside her matron friend, no words were spoken between them. The elder, overcome with fatigue, soon sank into a peaceful slumber, but the young enthusiast lay long awake, listening to the lone voice of the whippoorwill complaining to the night. Yet, notwithstanding this prolonged wakefulness, she arose early and looked out upon the lovely landscape. The rising Sun pointed to the tallest trees with his golden finger and was welcomed with a gush of song from a thousand warblers. The poetry in Elizabeth’s soul, repressed by the severe plainness of her education, gushed up like a fountain. She dropped to her knees and, with an outburst of prayer, exclaimed fervently, “Oh, Father, very beautiful hast thou made this earth! How beautiful are thy gifts, O Lord!”

To a spiritless, meek, and brave, the darker shades of the picture would have obscured these cheerful gleams, for the situation was lonely and the inconveniences innumerable. But Elizabeth easily triumphed over all obstacles by practical good sense and quick promptings of her ingenuity. She was one of those clear, strong natures who always had a definite aim in view and saw the means best suited to the end at once. Her first inquiry was what grain was best adapted to her farm’s soil, and being informed that rye would yield the best, “Then I shall eat rye bread” was the answer.

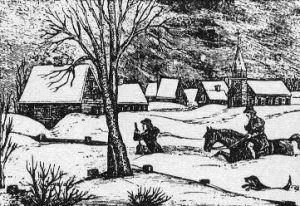

When winter came, and the gleaming snow spread its unbroken silence over hill and plain, was it not dreary then? It would have been dreary indeed to one who entered upon this mode of life for mere love of novelty or a vain desire to do something extraordinary. But the idea of extended usefulness, which had first lured this remarkable girl into an unusual path, sustained her through all her trials. She was too busy to be sad and leaned too trustingly on her Father’s hand to be doubtful of her way. The neighboring Indians soon loved her as a friend, for they always found her truthful, just, and kind. From their teachings, she added much to her knowledge of simple medicines. So efficient was her skill, and so prompt’ her sympathy, that for many miles around, if a man, woman, or child were alarmingly ill, they were sure to send for Elizabeth Haddon; and wherever she went, her observing mind gathered some hint for the improvement of farm or dairy. Her house and heart were both large and as her residence was on the way to the Quaker meeting house in Newtown, it became a universal resort to Friends from all parts of the country traveling that road and an asylum for benighted wanderers.

Late one winter’s evening, a tinkling of sleigh bells was heard at the entrance of the clearing; the hoofs of horses were crunching the snow as they passed through the great gate towards the barn. The arrival of strangers was a common occurrence, for the home of Elizabeth Haddon was celebrated far and near as the abode of hospitality. The toil-worn or benighted traveler there found a sincere welcome, and none who enjoyed that friendly shelter and abundant cheer ever departed without regret. But now, there was an unusual stir in that well-ordered family; great logs were piled in the capacious fireplace, and hasty preparations were made to receive guests who were more than ordinarily welcome. Looking from the window, Elizabeth recognized one of the strangers in the sleigh as John Estaugh, with whose preaching years before in London she had been deeply impressed, and ever since, she had treasured in her memory many of his words. It was almost like a glimpse of her dear old English home to see him enter, and stepping forward with more than usual cordiality, she greeted him, saying,

“Thou art welcome, friend Estaugh, the more so for being entirely unexpected.”

“And I am glad to see thee, Elizabeth,” he replied, with a friendly shake of the hand, “it was not until after I had landed in America that I heard the Lord had called thee hither before me, but I remember thy father told me how often thou hadst played the settler in the woods when thou was quite a little girl.”

“I am but a child still,” she replied, smiling.

“I trust thou art,” he rejoined, “and as for those strong impressions in childhood, I have heard of many cases when they seemed to be prophecies from the Lord. When I saw thy father in London, I even had an indistinct idea that I might be sent to America on a religious visit.”

“And hast thou forgotten, friend John, the ear of Indian corn my father begged of thee for me? I can show it to thee now. Since then, I have seen this grain in perfect growth, and a goodly plant it is, I assure thee. See,” she continued, pointing to many bunches of ripe corn that hung in their braided husks against the wall of the ample kitchen, “all that, and more, came from a single ear, no bigger than the one thou didst give my father. May the seed sown by thy ministry be as fruitful!” “Amen,” replied both the guests.

That evening a severe snowstorm came on, and the blast howled around the dwelling all night. The following day, it was discovered that the roads were rendered impassable by the heavy drifts. Elizabeth’s home had already been made the center of a settlement composed mainly of low-income families, who relied primarily upon her to aid them in cases of distress. That winter, they had been severely afflicted by a fever incident in a newly settled country. Elizabeth was in the habit of making them daily visits, furnishing them with food and medicines.

The storm roused her to an even more energetic benevolence than ordinary. Men, oxen, and sleds were sent out, and pathways were opened; the whole force of Elizabeth’s household, under her immediate superintendence, joined in the excellent work. John Estaugh and his friend tendered their services joyfully, and none worked harder than they did. His countenance glowed with the exercise, and a cheerful, childlike, out-beaming honesty of soul shone forth, attracting the kind but modest regards of the maiden. It seemed to her as if she had found in him a partner in the good work she had undertaken.

When the paths had been made, Elizabeth set out with a sled-load of provisions to visit her patients, and John Estaugh asked permission to accompany her. While they were standing together by the bedside of the aged and suffering, she saw her companion in a new and still more attractive guise. His countenance expressed a sincerity of sympathy warmed by rays of love from the Sun of mercy and righteousness. He spoke to the feeble and the invalid words of kindness and consolation, and his voice was modulated to a deep tone of tenderness when he took the little children in his arms.

The following “first day,” which the world’s people call the Sabbath, a meeting was attended at Newtown by the whole family, and then John Estaugh was moved by the Spirit to speak words that sank into the hearts of his hearers. It was a discourse on the trials and temptations of daily life, drawing a contrast between this course of earthly probation, with its toils, sufferings, and sorrows, and that higher life, with its rewards to the faithful beyond the grave.

Elizabeth listened to the preacher with meek attention; he seemed to speak to her for all the discourse lessons applied to herself. As the deep tones of the excellent man ceased to vibrate in her ears, and there was stillness for a full half hour in the house, she pondered over it deeply. The impression made by the young preacher seemed to open a new window in her soul; he was a God-sent messenger whose character and teachings would lift her still higher life and sanctify her mission with a holier inspiration.

A few days of united duties and oneness of heart made John and Elizabeth more thoroughly acquainted with each other than they could have been by years of ordinary fashionable intercourse.

They were soon obliged to separate, the young preacher being called to other meetings of his sect in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. When they bade each other farewell, neither knew that they would ever meet again, for John Estaugh’s duty might call him from the country ere another winter, and his hobbies in the new world were absorbing and continuous. With a whole heart but with the meekness characteristic of her sect, Elizabeth turned away from her daily round of good works with a new and holier zeal.

In May, they met again. John Estaugh, in company with numerous other Friends, stopped at her house to lodge while on their way to the quarterly meeting at Salem. The next day a cavalcade started from her hospitable door on horseback, for that was before the days of wagons in Jersey.

John Estaugh, always kindly in his impulses, busied himself with helping a lame and very ugly old woman and left his hostess to mount her horse as she could. Most young women would have felt slighted, but in Elizabeth’s noble soul, the quiet, deep tide of feeling rippled with an inward joy. “He is always kindest to the poor and neglected,” thought she; “verily, he is a good youth.”

She was leaning over the side of her horse to adjust the buckle of the girth when he came up on horseback and enquired if anything was out of order. She thanked him, with slight confusion of manner and a voiceless calm than her usual utterance. He assisted her to mount, and they trotted along leisurely behind the procession of guests, speaking of the soil and climate of this new country and how wonderfully the Lord had here provided a home for his chosen people. The girth began to slip, and the saddle turned so much on one side that Elizabeth was obliged to dismount. It took some time to readjust the girth, and when they again started, the company was out of sight. There was brighter color than usual in the maiden’s cheeks and unwonted radiance in her mild, deep eyes.

Young Quaker Man

After a short silence, she said, in a voice slightly tremulous, “Friend John, I have a subject of importance on my mind and one which nearly interests thee. I am strongly impressed that the Lord has sent thee to me as a partner for life. I tell thee my impression frankly, but not without calm and deep reflection, for matrimony is a holy relation and should be entered into with all sobriety. If thou hast no light on the subject, wilt thou gather into the stillness and reverently listen to thy inward revealings? Thou art to leave this part of the country tomorrow, and not knowing when I should see thee again, I felt moved to tell thee what lay upon my mind.”

The young man was taken by surprise. Though accustomed to that suppression of emotion that characterizes his religious sect, the color came and went rapidly in his face for a moment. But he soon became calmer and replied,

“This thought is new to me, Elizabeth, and I have no light thereon. Their company has been very pleasant to me, and their countenance ever reminds me of William Penn’s title page, Innocency, with her open face. I have seen thy kindness to the poor and wise household management. I have observed, too, that their warm-heartedness is tempered with a most excellent discretion and that their speech is ever sincere. Assuredly, such is the maiden I would ask of the Lord as a most precious gift, but I never thought of this connection with thee. I came to this country solely on a religious visit, and it might distract my mind to entertain this subject at present. When I have discharged the duties of my mission, we will speak further.”

“It is best so,” rejoined the maiden, “but one thing disturbs my conscience. Thou hast spoken of my true speech, and yet, friend John, I have deceived thee a little, even now, while we conferred on a serious subject. I know not from what weakness the temptation came, but I will not hide it from thee. I allowed thee to suppose, just now, that I was fastening the girth of my horse securely, but, in plain truth, I was loosening the girth, John, that the saddle might slip and give me an excuse to fall behind our friends; for I thought thou wouldst be kind enough to come and ask if I needed thy services.”

They spoke no farther upon this topic, but when John Estaugh returned to England in July, he pressed her hand affectionately as he said,

“Farewell, Elizabeth: if it be the Lord’s will I shall return to thee soon.”

The young preacher made but a brief sojourn in England. The Society of Friends in London appreciated his value as a laborer among them. It would have been pleased to see him remain, but they knew how fruitful of good had been his labors among the brethren in the wilderness and deemed it a wise resolution when he informed them that he should shortly return to America. Early in September, he set sail from London and reached New York the following month. A few days after landing, he journeyed on horseback to the dwelling where Elizabeth was awaiting him, and they were married at Newtown Meeting according to the simple form of the Society of Friends. Neither of them made any change of dress for the occasion; there was no wedding feast; no priest or magistrate was present; in the presence of witnesses, they simply took each other by the hand and solemnly promised to be kind and faithful to each other. The married pair then quietly returned to their happy home, prepared to resume together that life of good words and kind deeds which each had thus far pursued alone.

Three times, during the long period of their union, she crossed the Atlantic to visit her aged parents, and not seldom did he leave her for a season when called to preach abroad. These temporary separations were challenging for her to bear, but she cheerfully gave him up to follow his duty’s path wherever it might lead him. Amid her cares and pleasures as a wife, she neither grew self-absorbed nor, like many of her sexes, bounded her benevolence within the area of the household. Her heart was too large, her charity too abounding, to do that, and her sense of duty to her fellow men always dominated that narrow feeling that concentrates kindness on self or those nearest to one. While her husband performed his noble work in the care of souls, she pursued her career within the sphere where it was so allotted. As a housewife, she was notable; to her might be applied the words of King Lemuel, in the Proverbs of Solomon, celebrating and describing the good wife, “and her works praised her in the gates.” As a neighbor, she was generous and sympathetic; she stretched out her hand to the poor and needy; she was at once a guardian and a minister of mercy to the settlement.

When, after 40 years of happiness in wedlock, her husband was taken from her, she gave evidence of her appreciation of his worth in a preface which she published to one of his religious tracts entitled, “Elizabeth Estaugh’s testimony concerning her beloved husband, John Estaugh.” In this preface, she says:

“Since it pleased Divine Providence so highly to favor me with being the near companion to this dear worthy, I must give some small account of him. Few, if any, in a married state ever lived in sweeter harmony than we did. He was a pattern of moderation in all things; not lifted up with any enjoyments, nor cast down at disappointments; a man endowed with many good gifts, which rendered him very agreeable to his friends and much more to me, his wife, to whom his memory is most dear and precious.”

Elizabeth survived her excellent husband 20 years, useful and honored to the last. The monthly meeting of Haddonfield, in a published testimonial, speaks of her thus:

“She was endowed with great natural abilities, which, being sanctified by the Spirit of Christ, were much improved; whereby she became qualified to act in the affairs of the church, and was a serviceable member, having been clerk to the woman’s meeting nearly 50 years, greatly to their satisfaction. She was a sincere sympathizer with the afflicted, of a benevolent disposition, and in distributing to the poor, was desirous to do it in a way most profitable and durable to them and, if possible, not to let the right hand know what the left did. Though in a state of affluence regarding this world’s wealth, she was an example of plainness and moderation. Her heart and house were open to her friends, whom to entertain seemed one of her greatest pleasures. Prudently cheerful and well-knowing of the value of friendship, she was careful not to wound it herself nor to encourage others in whispering supposed failings or weaknesses. Her last illness brought great bodily pain, which she bore with much calmness of mind and sweetness of spirit. She departed this life as one falling asleep, full of days, like unto a shock of corn fully ripe.”

The maiden name of this gentle and useful woman has been preserved in Haddonfield, thus appropriately commemorating her manifold services in the early days of the settlement of which she was the pioneer mother.

By William Worthington Fowler, 1877. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

About the Author: William Worthington Fowler was a diverse man with a number of careers, including lawyer, stockbroker, politician, and author. This article was the prelude to his book Woman On The American Frontier: A Valuable And Authentic History, initially published in 1877. The article as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been heavily edited for the modern reader.

Also See: