By Charles M. Skinner

Soon after the rails were laid across Marshall Pass, Colorado, where they go over a height of 12,000 feet above the sea, an old engineer named Nelson Edwards was assigned to a train. He had traveled the road with passengers behind him for a couple of months. He met with no accident, but one night as he set off for the divide, he fancied that the silence was deeper, the canyon darker, and the air frostier than usual.

That morning, a defective rail and an unsafe bridge had been reported, and he began the long ascent with some misgivings. As he left the first line of snowsheds, he heard a whistle echoing somewhere among the ice and rocks. At the same time, the gong in his cab sounded, and he applied the brakes.

The conductor ran up and asked, “What did you stop for?”

“Why did you signal to stop?”

“I gave no signal. Pull her open and light out, for we’ve got to pass No. 19 at the switches, and there’s a wild train climbing behind us.”

Edwards drew the lever and sanded the track, and the heavy train got underway again. Still, the whistles behind grew nearer, sounding danger signals, and in turning a curve, he looked out and saw a train speeding after him at a rate that must bring it against the rear of his own train if something were not done. He broke into a sweat as he pulled the throttle wide open and lunged into a snowbank.

The cars lurched, but the snow was flung off, and the train went roaring through another shed. Here was where the defective rail had been reported. No matter. A greater danger was pressing behind. The fireman piled on coal until his clothes were wet with perspiration, and fire belched from the smoke-stack. The passengers, too, having been warned of their peril, had dressed and were anxiously watching at the windows, for talk went among them that a mad engineer was driving the train behind.

As Edwards crossed the summit, he shut off steam and surrendered his train to the force of gravity. Looking back, he could see by the faint light from the new snow that the driving wheels on the rear engine were bigger than his own and that a tall figure stood atop of the cars and gestured franticly. At a sharp turn in the track, he found the other train but 200 yards behind, and as he swept around the curve, the engineer who was chasing him leaned from his window and laughed. His face was like dough.

Snow was falling and had begun to drift in the hollows, but the trains flew on; bridges shook as they thundered across them; wind screamed in the ears of the passengers; the suspected bridge was reached; Edwards’s heart was in his throat, but he seemed to clear the chasm by a bound. Now the switch was in sight, but No. 19 was not there, and as the brakes were freed, the train shot by like a flash. Suddenly, a red light appeared ahead, swinging to and fro on the track. They also run into something behind them so as to crash into an obstacle ahead. He heard the whistle of the pursuing locomotive yelp behind him, yet he reversed the lever and put on brakes, and for a few seconds lived in a hell of dread.

Hearing no sound, now, he glanced back and saw the wild train almost leap upon his own—yet just before it touched it, the track seemed to spread, the engine toppled from the bank, and the whole train rolled into the canyon and vanished.

Edwards shuddered and listened. No cry of hurt men or hiss of steam came up–nothing but the groan of the wind as it rolled through the black depth. The lantern ahead, too, had disappeared. Now, another danger impended, and there was no time to linger, for No. 19 might be on its way ahead if he did not reach the second switch before it moved out. The mad run was resumed, and the second switch was reached in time. As Edwards was finishing the run to Green River, which he reached in the morning ahead of schedule, he found written in the frost of his cab window these words:

“A frate train was recked as yu saw. Now that yu saw it yu will never make another run. The engine was not under control, and four sexshun men wor killed. If yu ever run on this road again, yu will be recked.”

Edwards quit the road that morning and, returning to Denver, found employment on the Union Pacific. No wreck was discovered the next day in the canyon where he had seen it, nor has the phantom train been in chase of any engineer who has crossed the divide since that night.

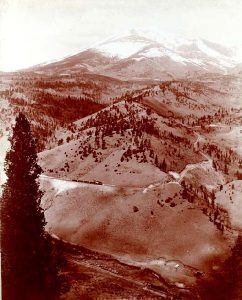

Marshall Pass in 1880, photo by William Henry Jackson.

By Charles M. Skinner, 1896. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

About the Author: Charles M. Skinner (1852-1907) authored the complete nine-volume set of Myths and Legends of Our Own Land in 1896. This tale is excerpted from these excellent works, which are now in the public domain.

Also See:

Ghost Stories from the Old West

The Railroad Blasts Across America (Railroad Tales and History)