Montserrat, Missouri, located between Warrensburg and Knob Noster in Johnson County got its start in 1867, at which time it was called Carbon Hill. What started out as a coal mining camp is now a ghost town with just a few area residents.

In 1863, coal was discovered in the area and was developed on a limited scale. It was worked first in the drifts of Clear Fork Creek. Two years later, more development occurred, and in 1866, the Missouri Pacific Railroad Coal Company sunk the first shaft. They operated successfully for four or five years until there was a management change of the railroad. They lost their patronage, became unprofitable, and the mining business was suspended for several years.

However, other companies and private individuals continued to operate with varying degrees of success. One of these men was John A. Gallaher, from nearby Knob Noster, who continued to work in the coal industry and did good business on a small scale.

The depth of the coalbed from the surface was estimated to be about 100 feet, with the thickness of each coal vein having an average thickness of about five feet. The coverage area of the coal was estimated to be three to five miles wide, east and west, and ten to fifteen north and south. The coal was classified as superior for railroad purposes because it produced immense heat, producing an incentive to continue coal mining in the area.

Montserrat, Missouri Post Office

In August 1870, a new townsite was platted by John Gallaher further west when the Missouri Pacific Railroad was extended to that point. Carbon Hill was located midway between Montserrat and Knob Noster. At that time, the people and businesses of the former community moved westward to the new town that Gallaher named Montserrat, after a jagged mountain about 30 miles northwest of Barcelona, Spain. It was thought that his choice of the name was inspired by the elevated site of the town and the serrated hills leading away south of it.

In 1872, the new town received a post office with C. B. Baker acting as the first postmaster. Baker also kept a saloon. Other early businessmen were W. H. Anderson, a carpenter who served as the justice of the peace; Drs. John W. Gallaher and J.L. Lea worked as physicians and also kept a drug store; Lea & Mayes kept a grocery store; S. J. LaRue also established a grocery store; H. B. McCracken was a drayman; D.S. Williams established a butcher shop, and J.C. Cooper was one of the pioneer blacksmiths. Several other saloons were operated by John Gibson, George James, and George Penn.

In 1875, Thomas H. Boyd came to Montserrat and became the superintendent of the mines owned by the Southwestern Coal Association. This company had bought or leased over 5,000 acres of land lying near Montserrat. Having prior experience in the coal industry, the company flourished under Boyd’s direction. He also ran a large general store.

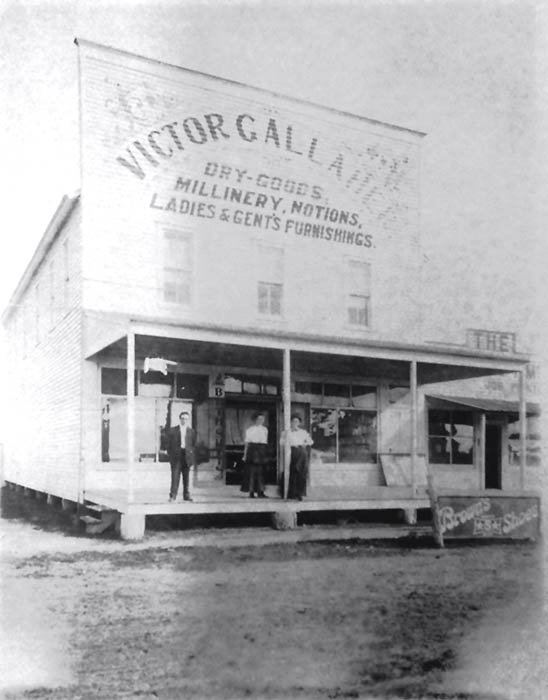

Victor Gallaher’s Store in Montserrat, Missouri

The Montserrat Coal Company was organized by John A. Gallaher in 1875. For several years, the company did extensive business, averaging 400 tons of coal on cars and in chutes daily.

Two years later, in 1877, great riots and strikes began among coal miners in the east, and the mania spread across the nation. Another series of strikes and clashes by railroad workers that summer brought the nation’s transportation to a grinding halt. In August, after the Montserrat mine workers did not receive a raise, they walked off the job angrily and went on a strike that lasted 30 days and cost the company more than $10,000.

The company then contracted with the manager of the state penitentiary to put 300 convicts to work in the mines. For the next three years, this arrangement worked well, with the profits going to the Montserrat Coal Company and the State of Missouri.

The Montserrat convict miners were housed in a three-story barrack that was surrounded by a 15-foot-tall wooden stockade. Armed guards stood at vantage points atop the stockade.

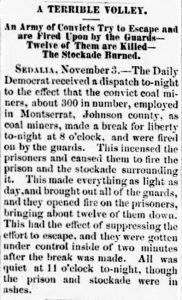

Coal Mine Escape

On the evening of November 3, 1877, Deputy Warden W. M. Todd brought out convict Allen Williams to be punished for lying to a guard. After Williams received a whipping, Todd sent prisoner Charles Butler to be punished for being “loud and unruly.” However, when Butler refused to leave the barracks, a group of armed guards was sent in to retrieve him.

When the guards went to retrieve Butler, the convict waved a red-hot poker from the stove at them while another prisoner hurled a stream of obscenities at the guards, which soon turned into a chorus of voices shouting, “Burn it! Burn it!” and an oil lamp was thrown directly at Todd. The lamp landed on the stairway leading up to sleeping quarters, and immediately, a raging inferno cut off any means of escape for those upstairs. Then, two other lamps were thrown, and the entire building was engulfed in flames.

“An indescribable scene of confusion followed in the third story. There were but two windows, and through these, the white convicts threw themselves headlong to the earth. It was a leap for life and no time to calculate the consequences. And out of the windows of the second story poured the black brigade, jumping at random, some head foremost, others alighting on their feet, others on their backs, and thus serving to break the fall of the next corner, all mixed up on the ground, an inextricable, tangled mass of human beings, groaning, shouting, swearing, while above and about them the flames of the burning stockade and quarters roared and hissed. The guards from all around had, in the meantime, rallied and opened a lively fire on those who were attempting to escape.”

— Jefferson City People’s Tribune

When it was over, 21 prisoners suffered burns and injuries from jumping or gunshot wounds, and three died. No convicts were able to escape, and the remainder soon went back to work in the mines. White and Butler, the main instigators of the riot, were taken to the penitentiary in leg irons and put in isolation cells to await their punishment.

In the meantime, Warden Willis returned to Montserrat with lumber and quickly rebuilt the stockade and quarters. The rest of 1877 passed without serious incident. The convicts continued to work in the mines for another two years.

By 1880, Montserrat, Missouri, was called home to 255 people and flourished with brick and rail yards, churches, and a grocery store. In addition to the coal miners, there were fine farms and stock lands where crops, including wheat, corn, hay, and oats, were grown.

In the next decades, the coal began to be worked out, and the population declined. By 1902, what was left of the coal was found to be of inferior quality, and most of the mines had been abandoned. By 1910, the population had dropped to 157, but Montserrat still had three churches, both a white and African American school, a physician, several stores, and a blacksmith shop.

Montserrat’s post office closed its doors forever in 1954. Today, the town is called home to just a few houses and a handful of people.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

The History of Johnson County, Missouri, The Printery, 1881

Johnson County & West Central Missouri

Thompson, Nora; Johnson County Missouri Historical Society Bulletin 1980s