The Miwok people are members of four linguistically related Native American groups indigenous to Northern California. Also spelled Miwuk, Mi-Wuk, or Me-Wuk, they traditionally spoke one of the Miwok languages in the Utian family. The name Miwok comes from the Northern Sierra Miwok word miw·yk meaning “people.”

Anthropologists commonly divide the Miwok into four geographically and culturally diverse ethnic subgroups.

The Plains and Sierra Miwok lived in the western slope and foothills of the Sierra Nevada, the Sacramento Valley, the San Joaquin Valley, and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

The Coast Miwok lived in Marin County and southern Sonoma County. This group included the Bodega Bay Miwok and Marin Miwok.

The Lake Miwok lived in the Clear Lake basin of Lake County.

The Bay Miwok lived in Contra Costa County.

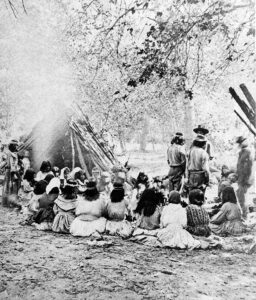

The Miwok lived mostly along the foothills of the Sierras and up into the mountains below the line of heavy winter snows. Northern branches of the group, known as the Plains Miwok and the Bay Miwok, lived along the Sacramento River and its delta. The Miwok lived in small groups of villages of 100 to 500 people. There was no centralized political authority before contact with European Americans in 1769. The Sierra branches that lived in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada constituted the greatest number of Miwok individuals and had more than 100 villages at the time of European contact.

Each group was led by a headman, who inherited the position from his father. The wealthy headman settled arguments and directed the hunting and food gathering. Assisting him were speakers and messengers, including a speaker who was a sort of sub-chief.

In mountain areas, the Miwok homes were made of bark slab layers leaning against each other in a cone shape. In the lower foothills and on the plains, houses were made around a frame of poles covered with bundles of grass or tule reeds or with mats woven from tule reeds. In the center of the house were a fireplace and an earth oven. Pine needles covered the floor, and tule reed mats and animal skins were used for sitting and sleeping.

The largest building in each community was the assembly house, used for dances and other gatherings. A hole three to four feet deep was dug in the ground to erect this building. The roof beams were held up by center posts and by the hole’s edge, creating a room 40 to 50 feet across. The roof beams were connected by smaller branches and then covered with brush, pine needles, and earth layers. There was a smoke hole in the center of the roof and a door on one side. The village sweathouse was made like the assembly house but much smaller.

The Miwok cultivated tobacco but were otherwise hunter-gatherers. The Sierra Miwok harvested acorns from the California Black Oak. The modern-day extent of the California Black Oak forests in some areas of Yosemite National Park is partially due to cultivation by Miwok tribes. They burned understory vegetation to reduce the fraction of Ponderosa Pine. Nearly every other kind of edible vegetable matter was used as a food source, including bulbs, seeds, and fungi.

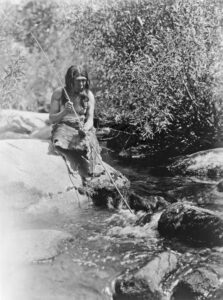

Animals were hunted with arrows, clubs, or snares, depending on the species and the situation. The Sierra Miwok depended on deer as their main source of meat. For the Plains Miwok, elk and antelope were easier to get. Each group traveled to the other’s area for hunting. Black and grizzly bears were hunted in the Sierras, though the Plains Miwok did not eat bears, foxes, or wildcats. Smaller animals like rabbits, beavers, squirrels, and woodrats were used as food. The Plains Miwok took salmon and sturgeon from the Sacramento delta waters. The Sierra Miwok caught trout in mountain streams. Grasshoppers were a highly prized food source, as were mussels for those groups adjacent to the Stanislaus River. The Coastal Miwok were known to have predominantly relied on food gathered from the inland side of the Marin Peninsula but also engaged in diving for abalone in the Pacific Ocean. They stored food for later consumption, primarily in flat-bottomed baskets.

Bows and arrows were used in hunting and in warfare. The Sierra Miwok used cedar wood to make the bows, which were backed with layers of sinew. Antlers were used to chip and shape the arrowheads. Also used in warfare were spears with obsidian tips. No shields or body armor were used.

The Sierra and Plains Miwok used twining and coiling methods for making baskets. Young willow branches were used as the foundation for both types of baskets. Redbud fibers were wrapped around the willow coils in the coiled baskets.

Tule reeds were woven together to make mats used on the floors of houses. The Plains Miwok used bundles of tules tied together around a frame made of willow poles to make canoes. Wooden paddles were used to propel the canoes. In the mountains, rafts made from two logs tied together with vines were used for crossing streams. String and cord were used to make nets for catching fish, birds, and small animals.

Northern Sierra Miwok women wore a deerskin wrap-around dress. The Central Miwok and Plains Miwok women wore a two-piece apron-type skirt made of deerskin, grasses, or shredded tule reeds. Miwok men wore a piece of deerskin around their hips. Men and women used blankets or robes made from animal skins for warmth in cold weather. Deer, bear, mountain lion, coyote, and rabbit skins were used to make robes.

Young children had their ears and noses pierced and wore flowers as ear and nose ornaments. Adults wore beads, shells, bones, and feathers as ear and nose ornaments. Both men and women had tattoos, usually with three lines running from the chin down the body. Hair nets were worn only by the village leaders, except at special ceremonies.

In trade, clamshell disks were used as money, though they were considered less valuable among the Miwok than among their neighbors to the north. Pieces of clamshell were shaped into small circles, holes bored in them, and strung on strings. Miwok men and women wore strings of clamshells as necklaces to show their wealth. Olivella shells and stone cylinders were also strung on strings and used in trade. The Sierra Miwok got salt and obsidian from groups on the east side of the Sierras and shells from those living on the sea coast. Baskets, bows, and arrows were traded between groups.

Some Miwok ceremonies were connected with religious practices. For these, special robes and feather headdresses were used. Other dances were held for fun and entertainment. Some Miwok dances included clowns called Wo’ochi, who were painted white and represented coyotes. The Miwok also had a grizzly bear ceremony, where the dancer pretended to be a bear, with pieces of obsidian attached to his fingers as claws.

The Miwok creation story and narratives are similar to those of other natives of Northern California. Miwok had totem animals identified with land and water. Personal names were often related to which group the person belonged. Geese, frogs, salmon, clouds, ice, deer, antelope, coyote, rock, and sand were related to water. The land side included bears, foxes, lizards, bluejays, fire, and drums. These totems controlled kinship and politics, regulating descent, marriage, and relations with other tribes. These totem animals were not thought of as literal ancestors of humans but rather as predecessors.

The Miwok historically used seven Miwokan languages that were part of the Penutian Family. This group of endangered languages was spoken in central California, ranging from the Bay Area to the Sierra Nevada. There are a few dozen speakers of the three Sierra Miwok languages, and in 1994 there were two speakers of Lake Miwok. The best-attested language is Southern Sierra Miwok, from which the name Yosemite originates.

In 1770, there were an estimated 500 Lake Miwok, 1,500 Coast Miwok, and 9,000 Plains and Sierra Miwok, totaling about 11,000 people. This is probably a low estimate because the estimate did not include the Bay Miwok.

The 1910 Census reported only 671 Miwok total, and the 1930 Census, 491. Today there are about 3,500 Miwok.

Miwok descendants numbered more than 5,700 in the early 21st century.

Federally recognized tribes include:

Buena Vista Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians

California Valley Miwok Tribe, formerly known as the Sheep Ranch Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians

Chicken Ranch Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians

Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, formerly known as the Federated Coast Miwok

Ione Band of Miwok Indians of Ione, California

Jackson Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians

Middletown Rancheria includes members of Pomo, Lake Miwok, and Wintun descent

Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, Shingle Springs Rancheria

Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians of the Tuolumne Rancheria

United Auburn Indian Community of Auburn Rancheria

Wilton Rancheria Indian Tribe

Tribes that have not been federally recognized include:

Calaveras Band of Mi-Wuk Indians

Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe of the Colfax Rancheria

Miwok of Buena Vista Rancheria

Miwok Tribe of the El Dorado Rancheria

River Valley Miwok Indians, formally known as Historical Families of Wilton Rancheria

Nashville-Eldorado Miwok Tribe

Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2023.

Also See:

Native Americans – The First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

California State Parks

Encyclopedia Britannica

Social Studies Fact Cards

Wikipedia