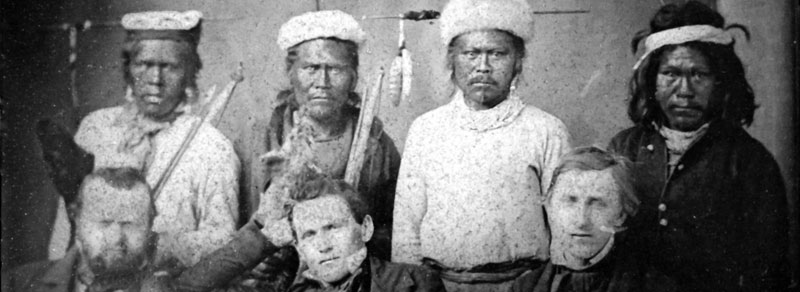

The Maidu are a Native American people of northern California who lived from the crest of the High Sierra, west to the Sacramento River, and south to the Cosumnes River. Collectively known as the Maiduan, four groups of closely related people have inhabited the land for thousands of years. These included the Mountain Maidu of Plumas and Lassen Counties, the Mechoopda of Butte County, the Konkow of Butte and Yuba Counties, and the Nisenan of Placer, Sacramento, and El Dorado Counties of California, and in Yuba, Nevada.

They spoke a language of Penutian stock. In Maiduan languages, Maidu means “man.”

In 1770, the estimated population of the Maidu was 9,000.

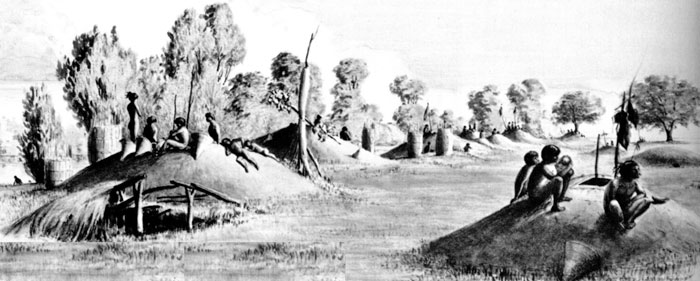

Each Maidu band resided in one of three habitats — the inland valleys, the Sierra Nevada foothills, or the mountains. The valley people were prosperous, but poverty was more common in the higher elevations. Those least exposed to inclement conditions had the most protective shelter, building large earth-covered communal dwellings in the valley.

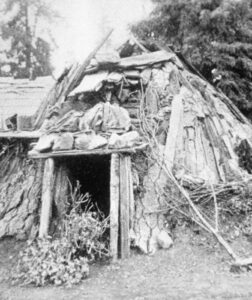

The foothill dwellers and mountaineers made more-fragile brush or bark lean-tos. Especially higher in the hills and the mountains, the Maidu built their dwellings partially underground to gain protection from the cold. These homes were sizable, circular structures 20 to 40 feet in diameter, with floors dug three to four feet below ground level. A pole framework was built over the floor covered with pine bark slabs. A central fire with a stone-lined pit and bedrock mortar to hold heat for food preparation was prepared on the ground level. The village ceremonial house was of the same design.

Several families shared a house, which they would build in the spring when the ground was soft. Some Maidu built cone-shaped houses from poles covered with bark. These were smaller than the earth lodges. A different structure was built for summer dwellings near where they were hunting or gathering food. These shelters had poles and a flat roof of oak branches, soil, and leaves.

Maidu lived in small villages or bands with no centralized political organization. Social organization was built around autonomous, yet allied, settlements, each claiming communal territory and acting as a single political unit. Communities comprised three to five villages, with an average of seven to ten houses in each village. The main village had a ceremonial earth lodge, where the headman often lived. His job was to advise the people and speak for them with other groups. Each community held certain lands on which they had hunting and fishing rights, and guards were posted to ensure people from other communities did not hunt or fish there. People did not usually travel more than 20 miles from home during their lifetime.

Like many other central California tribes, the Maidu practiced the Kuksu religion, involving male secret societies, rites, masks and disguises, and special earth-roofed ceremonial chambers. It was characterized by the Kuksu or “big head” dances. A traditional spring celebration for the Maidu was the Bear Dance when the Maidu honored the bear coming out of hibernation. The bear’s hibernation and survival through the winter symbolized perseverance to the Maidu, who identified with the animal spiritually. Rattles, flutes, and whistles were used in many of the dances. Some of the purposes of the rituals were naturalistic — to ensure good crops or plentiful game or to ward off floods and other natural disasters such as disease. The Pomo and the Patwin also followed the Kuksu cult system among the Wintun. Missionaries later forced the people to adopt Christianity, but they often retained elements of their traditional practices.

Among southern groups, the chiefs were hereditary, but among northern groups, they could be deposed and probably achieved their position through wealth and popularity. Leaders were typically selected from the pool of men who headed the local Kuksu cult. They did not exercise day-to-day authority but were primarily responsible for settling internal disputes and negotiating matters between villages.

Like many other California tribes, the Maidu were hunters and gatherers and did not farm. However, they tended local groves of oak trees to maximize the production of acorns, which were their principal dietary staple. Preparing acorns, a long and tedious process, was undertaken by the women and children. After shelling and cleaning the actors, they were ground into meal, and the tannic acid in the acorns was leached out by spreading the meal smoothly on a bed of pine needles laid over sand. Besides acorns, the Maidu supplemented their acorn diet with edible roots, seeds, berries, pine nuts, and other plants.

The men hunted deer, elk, antelope, bears, and smaller game, such as squirrels, rabbits, ducks, and geese, within a spiritual system that respected the animals. Sometimes a man hunted alone, and sometimes with a group of men, often using hunting dogs. The men fished for salmon, eel, and other river life. Several kinds of insects, including grasshoppers and crickets, were also eaten.

The Maidu made dugout canoes by burning out the middle of logs steered with one paddle or pole. They also made log rafts for crossing rivers by binding several logs with vines. Nets, bows and arrows, knives, and spears were used in hunting and fishing. Obsidian was used to make arrowheads, and knives and spears were made from hard black basalt rock, fastened to a wooden handle.

The Maidu traded with their neighbors. From the Achumawi to the north, they got obsidian and a green dye; from the Konkow, they got bows, arrows, deer hides, and several kinds of food. Clamshell disks that they got from the coast people served as money for the Maidu. The pieces of clamshell were made into polished beads.

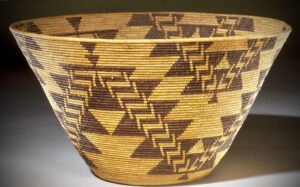

The Maidu women were exemplary basketweavers, creating highly detailed and useful baskets in sizes ranging from thimbles to huge containers that were ten or more feet in diameter. These extremely large baskets were utilized as above-ground acorn granaries to store the abundance of acorns for harder times. The weaving on some of these baskets is so fine that a magnifying glass is needed to see the strands. In addition to making closely woven, watertight baskets for cooking, they made large storage baskets, bowls, shallow trays, traps, cradles, hats, and seed beaters. They used wild plant stems, barks, roots, twigs, and leaves. By combining these different kinds of plants, the women made geometric designs on their baskets in red, black, white, brown, or tan. Utilizing coiled and twining systems, the products were sometimes handsomely decorated with feathers of brightly plumaged birds, shells, quills, seeds, and beads.

The Maidu did not need to wear much clothing. If the men wore anything in the warm summer weather, it was a simple piece of deerskin around their hips. Women wore a double apron, one section covering the front and the other covering the back. The apron was made of deerskin or of bark. In the winter, the Maidu wore moccasins made of deerskin stuffed with grass for extra warmth on their feet. Deer hide leggings were wrapped around the lower part of the legs, and they were robes made from deer or mountain lion skins over their shoulders.

The Maidu wore their hair long and hanging loose. Some men wore a net cap, sometimes decorated with feathers for ceremonies. Maidu women wore a basket cap made of tules. Tattooing was practiced by piercing the skin with a fish bone or pine needle and rubbing it in a dye or charcoal. Men often had vertical lines on the chin, and women tattooed their chest, arms, and abdomen.

The Maidu inhabited areas in the northeastern Sierra Nevada. Many examples of indigenous rock art and petroglyphs have been found here. Scholars are uncertain about whether the Maidu people created these or whether they date from previous indigenous populations. The Maidu incorporated these works into their cultural system and believe that such artifacts are real, living energies that are an integral part of their world.

In the 1910 census, the Maidu population, including the Konkow and the Niesan, was 1,100.

In the early 21st century, population estimates indicated more than 4,000 individuals of Maidu descent

There are several federally recognized bands today, including:

Berry Creek Rancheria of Maidu Indians

Enterprise Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

Greenville Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

Mechoopda Indian Tribe of Chico Rancheria

Mooretown Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, Shingle Springs Rancheria (Verona Tract)

Susanville Indian Rancheria

United Auburn Indian Community of the Auburn Rancheria

Other bands that are not federally recognized include:

Honey Lake Maidu Tribe

KonKow Valley Band of Maidu Indians

Nisenan of Nevada City Rancheria

Strawberry Valley Band of Pakan’yani Maidu, aka Strawberry Valley Rancheria

Tsi Akim Maidu Tribe of Taylorsville Rancheria

United Maidu Nation

Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe of the Colfax Rancheria

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2023.

Also See:

Native Americans – The First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

Encyclopedia Britannica

Roseville Historical Society

Social Studies Fact Cards

Wikipedia