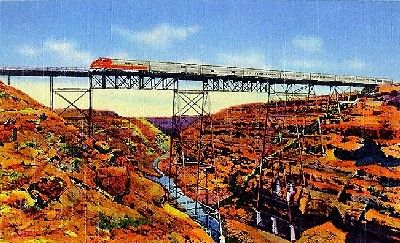

Canyon Diablo, Arizona.

By James Harvey McClintock in 1913

On March 21, 1889, an Atlantic and Pacific train was stopped at the Canyon Diablo, Arizona station by four robbers who, after searching the contents of the express strong box, fled northward. The robbery scene was in Yavapai County, so Sheriff William O. O’Neill took the trail with three deputies. After a chase of 300 miles and consuming two weeks, the posse finally sighted their men in Southeastern Utah, 40 miles east of Canyonville. Then came a pitched battle in which over 50 shots were fired, though the only effect was the wounding of one of the robber’s horses. The fugitives, leaving their horses behind, plunged into the mountains on foot, soon to be run down by the posse.

The capture included William D. Sitrin, “Long John” Halford, John J. Smith, and D.M. Haverick. Upon them was found about $1,000. A rather amusing incident was the attempt of citizens of Canyonville to arrest the desperadoes. Still, the attempt failed, for the large citizen’s posse was held up by the robbers and made to stack arms and retreat. The return to Arizona was made around Salt Lake. On the homeward journey, Smith escaped through a car window.

Another train robbery, September 30, 1894, occurred near Maricopa where a through express was boarded by Frank Armer, a Tonto Basin cowboy, only 20 years old, who climbed over the coal of the engine tender and at the muzzle of a pistol stopped the train where a confederate of Rodgers was in waiting. Little booty was secured. The two men, before this, had ridden in circles around the desert to throw pursuers off their track, but Indians, taking a broad radius, soon picked up the trail. Rodgers was caught far down the Gila, and Armer was taken at the home of a friend near Phoenix after a battle with Sheriff Murphy and officers in which he was wounded.

At Yuma Penitentiary, under a 30-year sentence, he made three attempts to escape. He dug a tunnel discovered when it had nearly connected his cell with the world beyond the Great Wall. A second time, when he broke for freedom from a rock gang, he had to lie down under a stream of bullets from a Gatling gun on the wall. A third time, he secreted himself while at outside work and eluded the guards but was run down in the Gila River bottom by Indian trailers. Finally, prostrated by consumption, he was released, barely in time to die at home in the arms of his mother. Rodgers was sentenced to a 40-year term, served only eleven, and then discharged for exemplary conduct.

Grant Wheeler and Joe George, on January 30, 1895, held up a Southern Pacific train near Willcox and robbed the through safe of $1,500 in paper money. The safe was broken open by dynamite upon the explosive piled sacks of Mexican dollars, of which in the car they were about $8,000. The result was satisfactory, the safe not only being cracked open but the express car nearly wrecked as well, the silver pieces acting upon it like shrapnel, sowing the desert around with bent and twisted Mexican money, which also was found deeply embedded in telegraph poles, and in the larger timbers of the car.

Sections of the telegraph poles and the car, stuck full of silver dollars, like plums in a pie, were valued souvenirs for years thereafter in railroad and express offices along the coast. Yet only $600 was lost from the silver shipment. The robbers escaped into the hills. They returned for more on February 26 when they stopped a train at Stein’s Pass but made the mistake of disconnecting the mail car instead of the express car, so they got no booty. W.M. Breakenridge took up the trail and was then in charge of the peace of the Southern Pacific line in southern Arizona. He trailed Wheeler into Colorado and ran him down near Mancos on April 25. The following day, the outlaw surrounded and, appreciating the hopelessness of his position after a brief exchange of shots with the pursuing posse, committed suicide.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

About the Author: James Harvey McClintock was born in Sacramento in 1864 and moved to Arizona at 15, working for his brother at the Salt River Herald (later known as the Arizona Republic). When McClintock was 22, he attended the Territorial Normal School in Tempe, earning a teaching certificate. Later, he served as Theodore Roosevelt’s right-hand man in the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War and became an Arizona State Representative. Between 1913 and 1916, McClintock published a three-volume history of Arizona called Arizona: The Youngest State (now in the public domain) in which this article appeared. McClintock continued to live in Arizona until his poor health forced him to return to California, where he died on May 10, 1934, at the age of 70. Note: The article is not verbatim, as spelling errors and minor grammatical changes have been made.

Also See: