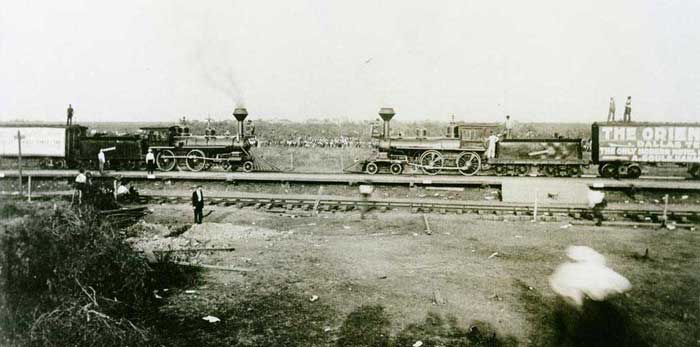

Locomotives meet for publicity photos before the “Crash at Crush” on, September 15, 1896. Photo by Jervice Deane.

There once was a town in Texas that existed only for a day, and exclusively for one event. To purposely crash two locomotives head-on, September 15, 1896.

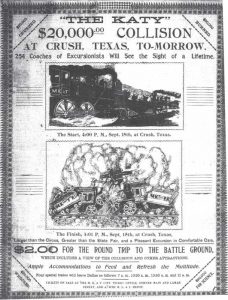

Crush, TX was an area north of Waco, in a shallow valley near the tracks of the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad, also known as the Katy. The “pop-up” town was named after William George Crush, a passenger agent for the Katy, who in 1895 had the outlandish idea of staging a train wreck as a way to generate passenger ticket sales. Texas, along with the rest of the country, was in a serious economic depression, and Crush convinced Katy company officials that his scheme would be a creative marketing ploy and attraction.

So in the summer of 1896, Texans were bombarded with advertising for the “Monster Crash”, daily preparation reports in many newspapers, and publicity stretching beyond the state border. The railroad would use two old locomotives for the event, Old No. 999 painted green and No. 1001 painted red, touring with the doomed steam engines across the state generating interest.

Thousands of Texans turned out to see the locomotives during their tour, and in early September several hundred Katy workmen began staging the town. They laid four miles of track off of the Waco-Dallas line that would be at a slight downward grade for both engines to the point of impact. A grandstand was constructed, along with three speaker’s stands, a bandstand, telegraph office, and a circus tent to act as a restaurant. The atmosphere was set with a huge carnival midway that featured game booths, drink stands, and medicine shows. And to put the final touch, they erected a special depot with a 2,100-foot platform and a sign welcoming passengers to Crush, Texas.

Safety was a concern, however, all but one of the engineers involved did not expect the train’s boilers to burst on impact. With most previous head-on-train collisions, the engines would force each other up into a V and the rest of the cars would accordion behind them, making a boiler explosion less likely. A safety perimeter of 150 yards was set up around the pre-determined collision point and no one would be allowed in the danger zone. “The place selected for the collision is a natural amphitheater, and nobody will have any trouble viewing the entire exhibition,” Crush told reporters.

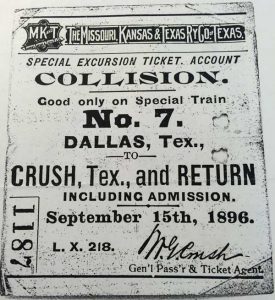

The exact location was kept secret up until the event, as people purchased $2 round trip train tickets from anywhere in the state to come see the stunt. They began arriving at daybreak on September 15, so many that some of the attendees were forced to ride on top of rail cars. What was expected to be around 20,000 quickly grew to more than 40,000 spectators, making the staged town of Crush the second largest city in Texas, at least for the day.

The exact location was kept secret up until the event, as people purchased $2 round trip train tickets from anywhere in the state to come see the stunt. They began arriving at daybreak on September 15, so many that some of the attendees were forced to ride on top of rail cars. What was expected to be around 20,000 quickly grew to more than 40,000 spectators, making the staged town of Crush the second largest city in Texas, at least for the day.

Families picnicked, listened to political speeches, and enjoyed the carnival-like atmosphere awaiting the crash. At 3 pm the trains were brought out for viewing to the cheering crowd with the crash set for an hour later.

At 4 pm, passenger trains were still arriving with spectators, so George Crush announced an hour delay.

Finally, just before 5 pm, the locomotives, each pulling 6 rail cars, slowly inched toward the middle for a salute, then backed away into position at opposite ends of the 4-mile track.

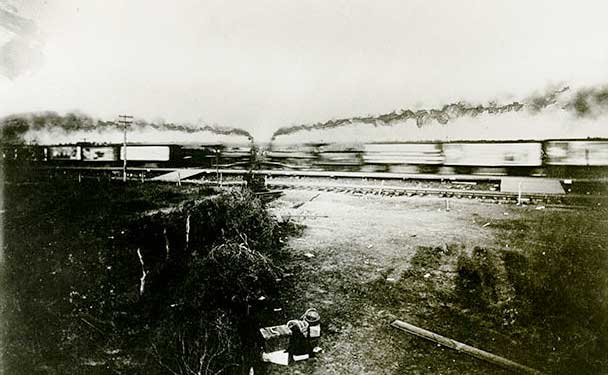

The spectacle was ready. Crush rode a white horse to the middle of the track, raised his white hat, then after a dramatic pause, whipped it down as the signal for the engines to start. As the crowd pressed forward for better views, the locomotive crews jumped to safety leaving the massive 35-ton iron monsters on 50 miles per hour course to disaster. Dramatic effect was added by placing small charges along the rail line creating warning blasts as the locomotives passed them.

Explosion at impact sends hot chunks of metal and wood up to 300 yards through the air. Photo by Jervice Deane, who lost his right eye during the explosion.

Crush and Katy rail officials had underestimated just how powerful the collision would be. It is thought that the trains hit with between 1 and 2 million pounds of force, and despite what the engineers thought would happen, the boilers on both exploded. The thunderous collision filled the air with flying metal as panicked onlookers ran to safety. Debris ranging from the size of a postage stamp to half a driving wheel was sent as far as 300 yards. Not everyone would make it out alive, as at least two were killed, and several injured. Some of the injuries occurring after the crash when spectators rushed to collect souvenirs, not realizing it would burn their hands. Waco based photographer Jervice Deane, whose pictures of the event are included in this article, lost his right eye to a flying bolt that lodged in his skull. Despite the injury, he survived.

The disaster was quickly cleaned up by railroad crews and souvenir hunters, and by nightfall, the town of Crush ceased to exist. Katy rail officials fired George Crush that night, anticipating a large backlash and lawsuits resulting from the larger than expected explosion. However the publicity stunt worked, train ticket sales increased, and Crush was re-hired within days, although his stint as a showman was over. The railroad quietly settled resulting lawsuits with cash and lifetime rail passes. Crush would remain with the railroad until his retirement in 1940.

A plaque 15 miles north of Waco in McLennan County marks the site of the “Crash at Crush”, which is near the town of West.

©Dave Alexander, Legends of America, September 2021.

Also See:

Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad

Ashtabula Train Wreck – Historic Accounts

Quirky Texas – Oddities and Unusual Attractions

Sources:

“Crash at Crush“, Allen Lee Hamilton, Texas State Historical Association

“Crush’s Locomotive Crash Was a Monster Mash“, J.R. Sanders, Wild West magazine, June 2010

KBUR – Waco Public Radio