While not nearly as famous as the Salem, Massachusetts, witch trials of 1692, witch hunts in Connecticut began decades earlier in 1647 and lasted intermittently until 1697. As a part of this greater madness, the Hartford Witch Panic began in 1662.

In the Puritan settlements of the New World, these highly religious, conservative, righteous, and intolerant people looked for something or someone to blame for any hardship. These might include illness, weather, Indian attacks, or even something as simple as food spoilage. Witchcraft was often the scapegoat, and their eyes would quickly turn to anyone who did not strictly conform to the harsh religious, social, and personal standards of the community. More often than not, those accused were women.

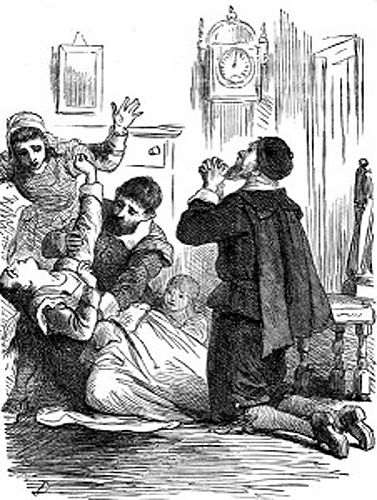

In the spring of 1662, Connecticut’s witch-hunting peaked in Hartford. The panic was set off with the death of eight-year-old Elizabeth Kelly, whose parents were convinced she had been bewitched. At about the same time, another young woman named Ann Cole began to have fits, and this, too, was blamed on witchcraft.

Soon, several other people in Hartford came forward, claiming to have been “afflicted” by demonic possession at the hands of their neighbors.

Many of the stories from Hartford were incredibly bizarre. One woman claimed that Satan had caused her to speak with a Dutch accent, another eyewitness said she saw her neighbors transform into large black hounds, and several people claimed to have seen witches dancing with the devil at night.

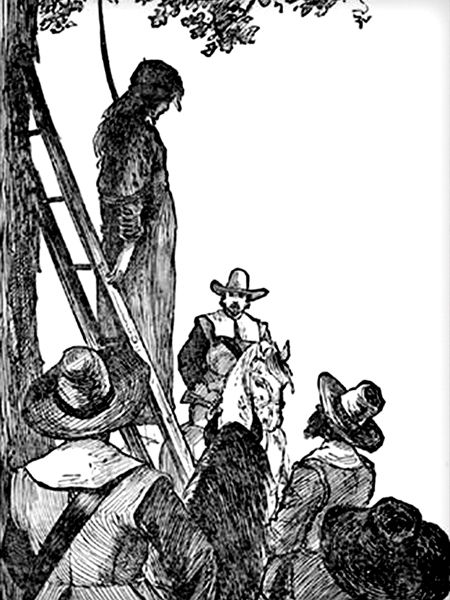

Between 1662 and 1663, 12 people were accused of witchcraft, and four were executed. Those accused included Goody Ayres, Judith Varlet, Nathaniel and Rebecca Greensmith, Andrew and Mary Sanford, Mary Barnes, John and Elizabeth Blackleach, Katherine Palmer, James Wakely, and Elizabeth Seager.

In 1663, Nathaniel and Rebecca Greensmith, Mary Barnes, and Mary Sanford were hanged.

Following these deaths, the Colonial Governor, John Winthrop, Jr., began to question the value of the “evidence” in the witch trials, as well as the possible agendas of the witnesses. As a result, he established more objective criteria for witch trials that required at least two witnesses for each alleged act of witchcraft, and in some cases, he personally intervened and overturned or reversed verdicts.

At that time, executions stopped, but the witch hunts continued.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Salem, Massachusetts Witchcraft Hysteria

Sources:

Connecticut Magazine, November 1899

List Verse

On Seger Mountain

Witch Hunts in Connecticut