Bloody Island, California

Bloody Island, California, derives its name from the Clear Lake Massacre of 1850, in which Captain Nathaniel Lyon, accompanied by soldiers and local white volunteers, invaded the island and killed 60 of the 400 Pomo Indians who had taken refuge there. Another 75 Indians were killed on the Russian River nearby. The soldiers killed 135 Indians, while two white men were wounded. The Indians fled to the island to save themselves after five Indians had killed two white men.

Charles Stone and Andrew Kelsey had been running cattle and using local Indians as free ranch labor. They “paid” the Indians four cups of wheat each day, which was inadequate to feed a large family. As a result, many Indians were starving. Stone, who was notorious for his mistreatment of Indians, killed a young Indian man who his starving aunt had sent to bring her family more wheat. Soon after this murder, two Indians by the names of Shuk and Xasis decided to borrow Stone and Kelsey’s horses for a hunting trip. Their purpose was to bring back meat to the hungry village. They could not leave their encampment during the day for fear of being seen and punished by the cattlemen. The hunting trip failed, and the horses borrowed by the Indians were returned to the ranchers, but both Indians feared that Stone and Kelsey would kill them if they found out the Indians had taken the horses. They decided to go to Stone and Kelsey’s place and kill them first. In December 1849, Shuk, Xasis, and three other Indians went to Stone and Kelsey’s place, killed them, and got food for their starving village. Many Indians then fled to the island in the middle of the lake, where they felt reasonably safe.

Pomo Indian in a headdress.

Captain Lyon arrived at the lake in the spring of 1850 with a detachment of soldiers. Since he could not reach the Indians’ hiding place, he secured two whaleboats and two small brass field cannons from the U.S. Army arsenal at Benicia, California. While waiting for the boats and field artillery, a party of local volunteers joined the expedition. Soldiers took the cannons aboard the whaleboats while the remaining body of mounted soldiers and volunteers proceeded to the west side of the lake. The two groups rendezvoused at Robinson Point, a little south of the island. The artillery was taken to the head of the lake to be as close as possible to the Indians.

In the morning, soldiers fired shots from the front to attract the Indians’ attention while the remaining force lined up on the opposite side of the island. The soldiers then fired the cannon, which sent the Indians across the island, where they met the rest of the detachment. Many Indian men, women, and children were killed. Some jumped into the water to flee, and some tried to hide on the island, but the soldiers overcame them.

Later in the year, Colonel Reddick McKee traveled to Lake County to negotiate treaties and establish the boundaries of the area’s Indian country. This was an important step because, at the time of the Bloody Island Massacre, there was no recognition of tribal rights in California. Most tribes were, therefore, unrepresented by the state’s political and judicial systems. Bloody Island represents the lack of due process under the law and exemplifies how the military was apt to administer justice when dealing with Indians.

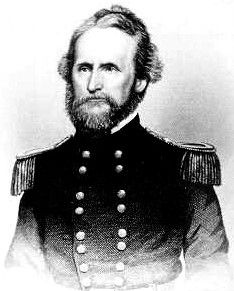

Nathaniel Lyon would become a Brigadier General for the Union Army and die at the Battle of Wilson Creek in 1861.

Bloody Island is one-quarter mile west of Highway 20 and about one and one-half miles south of the town of Upper Lake, north of Clear Lake, California. It is a state-registered landmark. Today, it is not apparent as an island until viewed from the south side because the surrounding lands have been reclaimed from the lake.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Source: National Park Service

Also See: