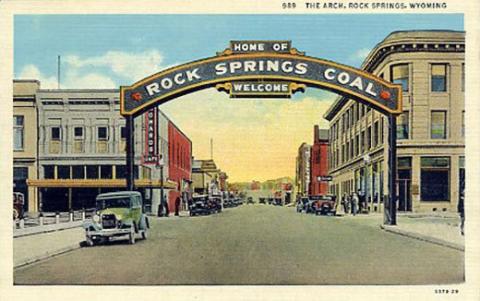

It was a dark day for Wyoming Territory and an even darker time for freedom and inclusion in America. September 2, 1885, brought violence and mayhem to Rock Springs, and in the end, 28 (some say up to 50) Chinese immigrants lost their lives, and over 75 homes were burned, causing what today would be almost $4 million in property damage. The historic event is now known as the Rock Springs Massacre.

Leading up to the Riot

Tension in the United States over Chinese immigration had been building for years in the late 1800s. So much so that in May of 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act into law. It was one of the most significant restrictions on free immigration in U.S. History. It was the first law implemented to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the country. Although the Act was originally designed to last for only 10 years, it would be renewed, and then made permanent, until finally being repealed by the Magnuson Act of 1943.

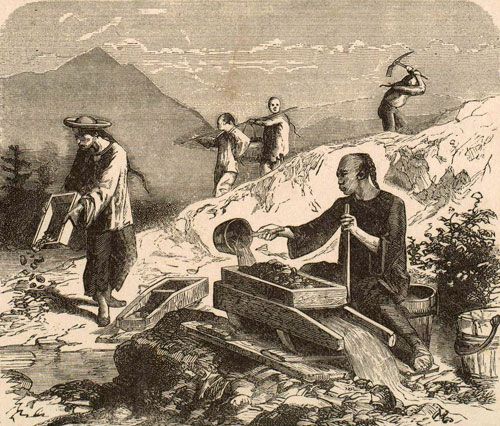

Animosity toward the Chinese had always been there but became prevalent after the Civil War. The 1870s saw an economy hurting, and as competition over finding gold and jobs increased, so did the ill will toward most foreigners. That ill will was especially felt toward the Chinese, who fled their homeland due to famine and political upheaval. Many of them came to California to work in the gold mines, but after being forced out of the mines, wound up taking low-paying jobs such as restaurant and laundry workers. As the post-war economy suffered, labor leaders and California Governor John Bigler blamed the Chinese for depressed wages, leading to further organization against the immigrants. Although California passed a law to ban anyone of Chinese or Mongolian race from entering the state in 1858, the State Supreme Court struck it down in 1862. As the population continued to increase, several California cities saw violence over the Chinese immigrants.

By the late 1870s, the sentiment toward Chinese immigration had reached Washington D.C., and in 1878 Congress passed legislation excluding the Chinese. However, it was vetoed by then-President Rutherford B. Hayes. In 1882, under a new President, Chester A. Arthur, they would successfully pass the legislation. Meanwhile, in Wyoming Territory, many Chinese were working the railroads, then afterward in the coal mines owned by Union Pacific Railroad. A leading voice against Chinese immigration, the Knights of Labor, established a chapter in Rock Springs in 1883 and, like in California, blamed the Chinese for depressed wages.

The Massacre

Newspaper accounts that followed the riot on that September day in 1885 wrote of building tensions and indicated that labor organizers had been planning a general strike “to bring matters to a crisis,” but the violence that ensued was not “part of the program.” Indeed, the tensions had been rising against Union Pacific, who, by paying the Chinese lower wages, left the white miners at Rock Springs believing they were being robbed of their own decent wages. In addition, a strike against Union Pacific ten years earlier led the company to replace the mostly Cornish, Irish, Swedish, and Welsh workers with Chinese strikebreakers. When the strike of ’75 was over, the company resumed mining with only 50 white miners, compared to 150 Chinese immigrants.

When things came to a head in 1885, there were 150 white miners and over 300 Chinese miners in Rock Springs. That summer, many white miners were out of work, but the Union Pacific Railroad was bringing in Chinese laborers by the dozens. In August, notices were posted from Evanston to Rock Springs demanding the Chinese expulsion, and on the night of September 1, white miners held a meeting. That next morning a fight broke out between ten white miners and Chinese laborers in the mine, resulting in two of the Chinese being badly beaten, one of whom would later die from his injuries. The white miners then left the mine to strike against the company. More white miners were gathering in town for a Knights of Labor meeting, and thus the mob began to grow.

While some white miners chose to go to the saloons instead of participating in what was coming, a Union Pacific official, anticipating trouble, convinced the saloons and grocers to close by early afternoon. About that time, the mob of white miners, now armed, moved toward Chinatown to drive out all Chinese immigrants from the town. The mob gave them an hour to leave and the Chinese, now in a panic, agreed. But the mob grew impatient and, thinking that the Chinese were preparing to defend themselves, began to advance on them with “much shooting and shouting.”

An 1886 article on the massacre published by Franklin Press states:

“Without offering any resistance, the Chinamen snatched up whatever they could lay their hands on and started east on the run. Some were bareheaded and barefooted; others carried a small bundle in a handkerchief, while a number had rolls of bedding. They fled like a flock of frightened sheep, scrambling and tumbling down the steep banks of Bitter Creek, then through the sagebrush, and over the railroad, and up into the hills east of Burning Mountain. Some of the men were engaged in searching the houses and driving out the stray Chinamen who were in hiding, while others followed up the retreating Chinamen, encouraging their flight with showers of bullets fired over their heads…”

“…Soon a black smoke was seen issuing from the peak of a house in “Hong Kong,” than from another, and very soon eight or ten of the largest of the houses were in flames. Half choked with fire and smoke, numbers of Chinamen came rushing from the burning buildings, and, with blankets and bedquilts over their heads to protect themselves from stray rifle shots, they followed their retreating brothers into the hills at the top of their speed.”

Chinese immigrants present that day would recount their horrifying experience to the Chinese consulate in New York City.

“Whenever the mob met a Chinese, they stopped him and, pointing a weapon at him, asked him if he had any revolver, and then approaching him they searched his person, robbing him of his watch or any gold or silver that he might have about him, before letting him go. Some of the rioters would let a Chinese go after depriving him of all his gold and silver, while another Chinese would be beaten with the butt ends of the weapons before being let go. Some of the rioters, when they could not stop a Chinese, would shoot him dead on the spot, and then search and rob him. Some would overtake a Chinese, throw him down and search and rob him before they would let him go. Some of the rioters would not fire their weapons but would only use the butt ends to beat the Chinese with. Some would not beat a Chinese but rob him of whatever he had and let him go, yelling to him to go quickly. Some, who took no part either in beating or robbing the Chinese, stood by, shouting loudly and laughing and clapping their hands.”

The riot continued into the night, with the mob demanding some of the Union Pacific mine management and anyone else they deemed “helping the Chinese” to leave town. Sheriff Joe Young came down from Green River that evening, and guards were out all night protecting Rock Springs citizens’ property; however, all was quiet ‘in town. Chinatown continued to burn, and “All the night long the sound of rifle and revolver was heard, and the surrounding hills were lit by the glare of the burning houses”.

The Aftermath

The next day revealed the horror of the event, with bodies burned in the ashes of homes and found shot dead in the hills while trying to escape. Wyoming Territorial Governor Francis Warren telegraphed President Grover Cleveland on September 4 the following.

“Unlawful combinations and conspiracies exist among coal miners and others, in the Uintah and Sweetwater Counties in this Territory, which prevents individuals and corporations from enjoyment and protection of their property and obstruct execution of laws. Open insurrection at Rock Springs; property burned; sixteen dead bodies found; probably over fifty more under ruins. Seven hundred Chinamen driven from town, and have taken refuge at Evanston and are ordered to leave there. Sheriff powerless to make necessary arrests and protect life and property unless supported by organized bodies of armed men. Wyoming has no territorial militia; therefore I respectfully and earnestly request the aid of United States troops, not only to protect the mail and mail-routes but that they may be instructed to support civil authorities until order is restored, criminals arrested, and the suffering relieved.”

Under orders from the War Department, General Howard sent four companies of troops to the scene, and by September 5, around 80 troops were in Rock Springs and as many in Evanston, with orders to protect the United States mail. Meanwhile, the striking white miners continued to prevent Union Pacific from operating in Rock Springs and the Almy mines near Evanston. On September 7, the Chinese were given notice not to enter the mines at Almy, or they would be fired upon. The mines at Almy were then closed.

The local Rock Springs newspaper defended the riot to an extent, as well as some other newspapers. Still, overall, Wyoming newspapers railed against the massacre while supporting the cause of the white miners, laying the blame on Union Pacific and their employment practices. Things finally began to settle down in Rock Springs by mid-September, and many of the Chinese survivors had been escorted back, still employed by the coal mines, but the white workers continued to strike. The Knights of Labor did not support the white miners continuing to strike in Rock Springs because they did not want to be seen as condoning the violence there. It was later emphasized that the Knights of Labor organization was not involved in the massacre and that only some of its members took part. A debatable claim when considering the high rhetoric leading up to the event. When the Union Pacific Coal Department reopened the mines, they fired 45 white miners in connection with the violence. Justice beyond that wouldn’t come though. Although 16 men were arrested, a Sweetwater County grand jury refused to bring indictments, stating: “no one has been able to testify to a single criminal act committed by any known white person that day.”

After the riot, tensions rose further between the U.S. and the Chinese government over the incident, with one China official suggesting that Americans in China may be the target of revenge for Rock Springs. The rising anti-American sentiment was noted in Hong Kong, and American diplomats warned that the backlash could ruin U.S. trade with China. These tensions lead to the U.S. government agreeing to pay compensation for the property damage but not for the actual victims. Secretary of State Thomas Bayard, working with Congress, presented the compensation as a monetary gift, not as any legal declaration of responsibility. Bayard had expressed to Chinese officials in Washington that it was the Chinese laborers’ fault that tensions had escalated so far, expressing the widely held view that their resistance to cultural assimilation precipitated the hatred and that racism against Chinese was typically found among other immigrants, rather than the majority of Americans.

The Rock Springs Massacre led to more incidents against the Chinese in Washington Territory, Oregon, and other states. Historians see it as the worst, most significant instance of anti-Chinese violence during the 1800s in the United States. Federal troops would remain outside Rock Springs at Camp Pilot Butte until the camp was closed in 1898.

© Dave Alexander, Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Chinese Immigration to the United States

Sources:

The Chinese Massacre at Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory, September 2, 1885 – Boston: Franklin Press – Rand Avery & Co., 1886

Wikipedia