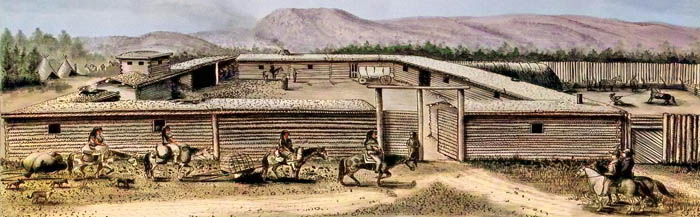

Fort Bridger, Wyoming, was first established in 1843 as a trading post by Jim Bridger and his partner, Pierre Louis (Luis) Vasquez, on Black’s Fork of the Green River. Planning to trade both with the Indians and the westward-bound emigrants, the first “fort” was composed of two double-log houses about 40 feet long, joined by a pen for horses, and provided a small blacksmith shop.

Westward-bound emigrants who looked forward to the stop and a break from the long monotonous days of traveling were often disappointed upon their arrival at Fort Bridger. Unlike Fort Laramie, a “civilized” outpost, in their minds, Fort Bridger was little more than a crude collection of rough-hewn log buildings.

Emigrant Edwin Bryant would say of the fort, “The buildings are two or three miserable log cabins, rudely constructed and bearing but a faint resemblance to habitable houses.”

Another, named Joel Palmer, remarked: “It is built of poles and dabbed with mud; it is a shabby concern. Here are about 25 lodges of Indians, or rather, white trapper’s lodges, occupied by their Indian wives. They have a good supply of skins, coats, moccasins, which they trade for flour, coffee, sugar, etc.”

When the Mormon Pioneer Company reached the fort on July 7, 1847, they spent a day there but considered the prices of supplies too high at the remote trading post. When a group of Mormons settled near Fort Bridger, tensions arose between Bridger and the new settlers. The following year, the Mormon settlers reported to Brigham Young in Salt Lake City that Bridger was selling liquor and ammunition to the Indians, violating federal law.

Young, who was a federal Indian agent, determined to stop the practice, and on August 26, 1853, a Mormon militia of forty-eight men started for Fort Bridger from Salt Lake City. However, Jim Bridger was warned and escaped minutes before the Mormons arrived. When the Mormons arrived, they discovered plenty of liquor, which they destroyed, but found no ammunition.

That same year, the Mormons established Fort Supply, specifically for Mormon emigrants, about 12 miles south of Fort Bridger.

In retaliation, Bridger wrote a letter to General B.F. Butler, a U.S. Senator, in October 1853, claimed he was “robbed and threatened with death by the Mormons” and that over $100,000 of his goods and supplies had been stolen.

The following spring, Brigham Young sent fifteen well-armed men to take control of Fort Bridger and the Green River ferries, which would become an integral part of the Mormon settlement plan. The men built a large stone wall around the fort and several stone buildings.

The Mormons controlled the fort for the next year until Jim Bridger returned in July 1855. The Mormons asked him to sell, but he refused when he noticed the improvements. The following month, he finally agreed to the sale, under some pressure from the Mormon militia. Agreeing on a sale price of $8,000, $4,000 was paid immediately, and the balance was to be paid in November 1856, fifteen months later.

In the meantime, tensions continued to broil between the Mormons and other settlers of the area. In the Presidential Election of 1856, the Republicans attacked polygamy and slavery, and though Democrat James Buchanan was elected, he too opposed the practice of polygamy. More importantly, he opposed the dominance of Utah Territory by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons,) seeing it as a violation of American principles. These tensions soon led to the “Utah War” of 1857- 58. In the meantime, Jim Bridger never received the balance of $4,000 owed him for his fort.

The fort became a point of contention in the fall of 1857 when the U.S. Army, under the command of General Albert Sidney Johnston, marched across the high plains planning to use the fort as a base to enter Utah Territory. However, before the Army arrived, “Wild Bill” Hickman and his brother burned both Fort Bridger and Fort Supply on the night of October 7 to keep them from falling into the hands of the approaching United States Army. As a result, Johnston’s Army, with little shelter and inadequate food supplies, endured an insufferable winter awaiting the spring thaw.

Though the “Utah War” did not involve battles between the Army and the Mormon militia, property was significantly destroyed. At the height of the conflict, more than 100 California-bound settlers from Arkansas were killed by Mormon militia and local Paiute in the Mountain Meadows Massacre in September 1857.

At the end of hostilities, Brigham Young paid the remaining $4,000 owed on the fort during the peace negotiations and thought he owned it. Though the government accepted the payment, they rejected Brigham Young’s claim to the fort and refused to recognize Jim Bridger’s continuing claims to the fort.

Instead, the fort was profitably run by William Alexander Carter, who had come with Johnston’s Army as a sutler or storekeeper. He stayed there with his family, rebuilding and restocking the fort, eventually becoming wealthy. A highly respected man, he was soon known as “Mr. Fort Bridger,” Wyoming’s first millionaire.

The garrison dwindled in numbers during the Civil War as soldiers were sent back east. However, regular troops returned in 1866, utilizing the fort as a base of operations for southwestern Wyoming and northeastern Utah. The post guarded stage routes and the transcontinental telegraph line accommodated a Pony Express station, patrolled emigrant trails, took action against Indian raids, guarded the miners who moved into the South Pass and Sweetwater region and protected and supplied workers building the Union Pacific Railroad not far to the north.

Treaties were signed at the fort with the friendly Shoshone in 1863 and 1868, the second creating a reservation east of the Wind River Mountains. Although strategically located, the fort never served as a base for any of the significant military expeditions of the 1870s against the Indians in the region. Still, some of the garrisons were reassigned for fighting purposes. Temporarily abandoned in 1878, the post was reactivated in 1880. A decade later, it was abandoned by the military.

In the meantime, Jim Bridger continued to press for his claim for payment, gaining no resolution by his death in July 1881. Only after almost two decades of effort by his descendants was the matter finally settled when Congress appropriated $6,000 for the family.

Successful sutlers, William Carter’s family continued to live at the fort until 1928, when it was sold to the Wyoming Historical Landmark Commission for preservation.

Today, the fort is a Wyoming State Park with a group of well-preserved and maintained structures. Some restoration has been accomplished, including the 1884 barracks building, which now houses a museum. Crumbling ruins of the commissary building and the old guardhouse, built in 1858, are visible. In better condition are the 1884 “new” guardhouse, the 1858 sentry box, and the officer’s quarters. Also standing is the sutler’s store, Pony Express stables, post office, a group of lesser buildings, and a portion of the wall constructed by the Mormons. The foundations of other buildings are marked. Interred in the cemetery are Bridger’s daughter and Judge W. A. Carter, a pioneer rancher in the area. Portions of the original fort grounds and some buildings are located on privately owned property outside the State-owned area.

Fort Bridger is south of I-80 at Exit 34.

Contact Information:

Fort Bridger State Historic Site

PO Box 112

Fort Bridger, Wyoming 82933

307-782-3842

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See: