West Virginia Coal Mine Disasters

Hawk’s Nest Strike – First Strike in West Virginia

Paint Creek & Cabin Creek Strikes of West Virginia

Revitalizing Abandoned Coal Mining Towns: Exploring Opportunities for Repurposing and Sustainability

A large part of West Virginia’s heritage is its coal mining history. Coal has contributed significantly to the state’s economic, political, and social history since it was first discovered in Boone County in 1742. These energy-rich bituminous coal deposits occur in all but two of West Virginia’s 55 counties. The industry has also been a center of controversy and criticism, giving rise to battles over labor, environment, and safety.

Coal was known to exist in Western Virginia from colonial times and was officially reported when John Peter Salley took an exploratory trip across the Allegheny Mountains in 1742. He reported finding a large outcropping of coal along a tributary of the Kanawha River in Boone County, which he and his companions named the Coal River. This report was made over a century before West Virginia became a state.

However, coal would not be exploited for years as there was a great abundance of wood and few manufacturing industries. Small amounts of coal were used by settlers close to an outcrop, blacksmiths, and iron forges.

The erection of salt furnaces in Kanawha County beginning in 1797 provided the initial stimulus to coal mining. In 1810, Conrad Cotts opened the first commercial coal mine near Wheeling for blacksmithing and domestic use. In 1811, the first steamboat on the Ohio River burned coal.

By 1817, coal began to replace charcoal as a fuel for several Kanawha River salt furnaces. Coal was used to heat the brine from salt beds underneath the river. In the 1820s and 1830s, the growth of the salt industry led to the opening of several mines to supply furnace fuel.

In 1840, total coal production for the State was about 300,000 tons, of which 200,000 tons were used in 90 Kanawha salt furnaces. Steamboats also consumed great quantities of coal; factories and homes in Wheeling used the rest.

More coal fields began to develop in the following two decades as demand increased to power factories, and fuel was needed for locomotives and steamships.

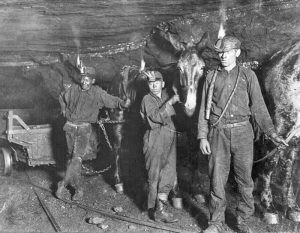

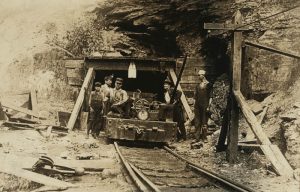

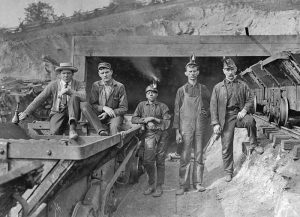

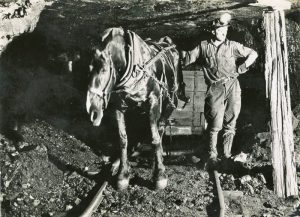

The work was hard, with miners using picks and shovels. The coal was dug out, shoveled into baskets and sacks, and carried away. Later, sleds, wheelbarrows, and carts came into use in deep mining, hauled by oxen, mules, goats, dogs, and sometimes men.

Between 1840 and 1860, many coal companies were organized, and corporations were created to encourage financial investments. As early as the 1850s, immigrants from Wales, England, and Scotland were brought to work in the coal mines.

Afterward, the salt industry began to decline, but the demand for coal continued due to the use of coal oil for lighting. In northern West Virginia, James Otis Watson, sometimes regarded as the father of the West Virginia coal industry, learned all he could about coal mining and, in 1852, organized the Montana Mining Company. He was the first operator in West Virginia to ship coal by rail. Utilizing the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad marked a boom in the northern West Virginia coalfields.

By 1860, 25 independent coal companies had been organized, employing more than 1,000 workers.

When the Civil War began, the industry’s growth slowed. The Kanawha Valley mines were closed. Confederate troops set up camps in the valley, and many locks and dams along the river were destroyed, preventing shipping. Farther north, the Elkins and Fairmont fields remained active, providing coal for the Union via the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. The coal was used for railroad engines and heating in the east.

Following the Civil War, an awakening of interest in the State’s mineral resources brought a new era of development and growth to the coal industry. In 1867, 490,000 tons of coal were produced in West Virginia.

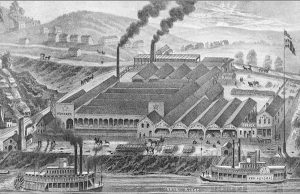

The commercial coal industry began to grow with the arrival of the railroads in the coalfields in southern West Virginia. In 1873, the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad wound its way through the New River and Kanawha coalfields that connected Richmond, Virginia, and Huntington, West Virginia. Many of these coalfields owed their success to the railroad.

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad did not attempt to control the land along its tracks, so independent speculators and mining companies took up the mineral lands in the New and Kanawha Valleys.

In January 1880, the Hawks Nest Coal Company Strike occurred. It would be the first of many coal mining strikes in West Virginia. It was the first time the West Virginia militia was used to stop a coal mine strike and set a president for handling future mine strikes.

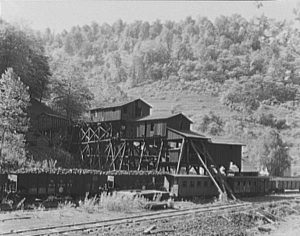

In the 1880s, many mining operators built company towns because most of the mines were located too far from established towns. The towns consisted of inexpensive homes, a company store, a church, a post office, and often recreation facilities for the miners and their families. These unincorporated towns had no government institutions and were entirely run by coal companies.

In these towns, the miners could get advanced credit on their earned wages in scrip to pay for daily necessities at the company store. This simplified bookkeeping and eliminated the need for the coal company to keep large amounts of currency on hand. The earliest coal scrip dates back to about 1883. Each mine had its own scrip symbols on the tokens, which could only be used at the local company store.

Homes were distributed to miners in an economic and social hierarchy, with managers living in better houses. The mine superintendent usually lived in a mansion with 10 to 20 rooms located on a large lot with trees and well-kept grounds. Lower-quality housing, often situated on the edge of the community, was occupied by white miners. Blacks and immigrants were separated in less desirable areas near the mine entrances or along hillsides.

Company towns varied from place to place, with some being better than comparable independent communities while others being filthy and decrepit. Some were harshly repressive, and others largely free. The life span of the company town usually was 50 to 75 years, or as long as the coal seams were productive.

In 1883, the major rail lines were completed, and production totaled nearly three million tons. One of the major southern coalfields was the Flat Top-Pocahontas Field, primarily in Mercer and McDowell Counties. This region first shipped coal in 1883 and grew quickly.

These coalfields were linked to the national markets by the Norfolk & Western Railroad. Unlike the C&O Railroad, the N&W Railroad and its land company purchased hundreds of thousands of acres of coalfields, which it leased to operators. These pioneer operators generally had relatively little capital but had the willingness to do the difficult physical labor and high levels of risk. Coal operators John Freeman and Jenkin Jones, who later became quite wealthy, reportedly arrived in Mercer County with little more than a pick and a shovel.

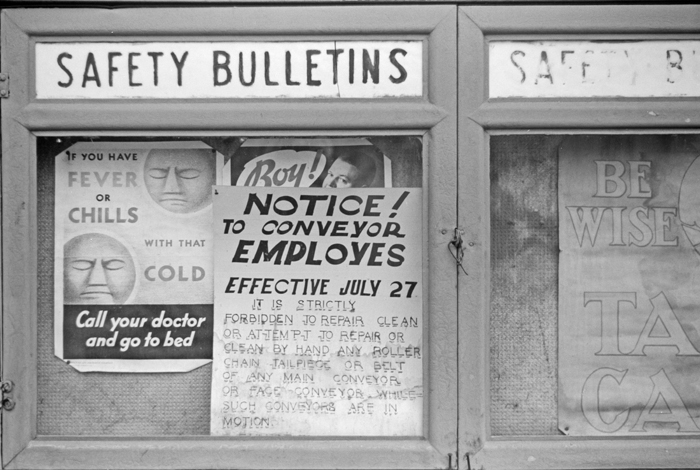

In February 1883, due to the poor conditions in the mines, the West Virginia Legislature passed the first laws regarding coal mining in the state. The law provided for a qualified mine inspector, and the governor appointed Oscar A. Veazey. His job required him to inspect all mines for adequate safety conditions and prepare an annual report on conditions and activities. It also required reporting all mine fatalities and the victims’ names. In 1894, Veazey proposed the first comprehensive mine safety laws. However, the Legislature would not pass the first laws until 1887.

As the coal industry grew, most of the mining was supported by out-of-state capital and was run by out-of-state superintendents. These men brought in cheap foreign labor, especially from southern Europe, and often abused them with long working hours, poor medical care, and generally inferior living conditions.

The first recorded mine disaster in West Virginia occurred on January 21, 1886, at the Mountain Brook Mine in Newburg. An open light ignited the gas and dust explosion, which killed 29 people.

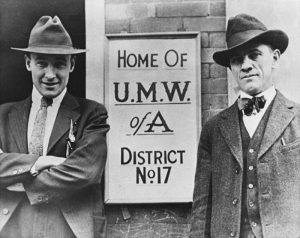

By 1887 coal production had grown to 4.9 million tons. In 1890, the United Mine Workers of America state union was organized in Wheeling to push for better conditions.

Massive capital investments poured into the West Virginia coal industry, producing the region’s social and economic transformation. Many people were needed in the mountains to operate the mines successfully, and in many places, the population was too small to satisfy the demand for labor. This resulted in companies recruiting workers from outside the region and building company towns near the railroads.

With many miners recruited from outside the state, the ethnic and racial mixture changed. In some southern counties, the foreign-born and African-American populations combined to outnumber native-born whites. These areas were often improved with the previously unavailable or scarce social services, such as electric power, public schools, and public libraries. With this growth, retail establishments and the number of professionals like doctors and dentists also increased.

As the coal industry grew, mining methods and laws changed rapidly. Progress in mechanization was slow, as operators did not want to pay for expensive new equipment, and miners feared being replaced by it. However, by 1890, electric coal cutting, loading, and hauling machines were used, and mules were used less frequently. In the early 1900s, electric locomotives moved underground coal, replacing the mules altogether.

The legislature passed in 1897 an act expanding the number of inspection districts to four and created the position of Chief Mine Inspector. Also, that year the mining laws were printed in book form for the first time. Between 1897 and 1904, coal production increased by nearly 125%, and the need for a Department of Mines was warranted. In July of 1905, the West Virginia Department of Mines was created and increased the number of inspectors to seven.

As the C&O railway expanded its lines in southern West Virginia, coal became more available for marketing, and the coalfields prospered. The Logan Field, lying in Logan and Wyoming Counties, was developed in 1904 when the railway finally reached the fields. Soon, Logan became the largest coal-producing county in the state, dominated by the Island Creek Coal Company.

The West Virginia Department of Mines was established in 1905 to enforce inspection laws. That year, six coal mining disasters occurred, the highest number in any year.

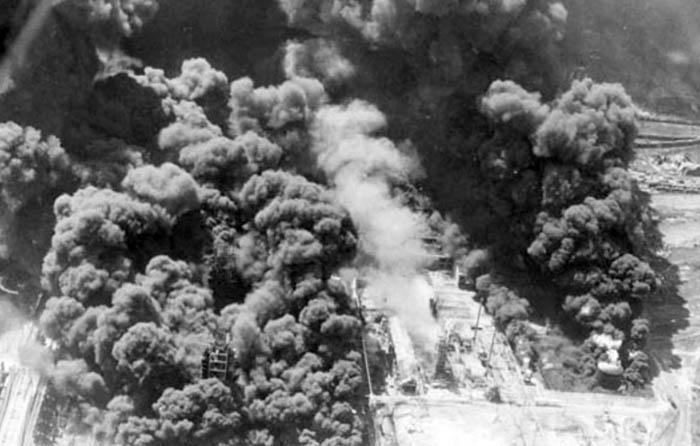

On December 6, 1907, the Fairmont Coal Company’s interconnected Number 6 and 8 mines at Monongah exploded, killing at least 361 miners, the worst coal mining disaster in U.S. history. People could feel the impacts from the explosions as far as eight miles away. The force of the event violently threw some people and animals, and many buildings were destroyed. To this day, officials aren’t sure of the cause. Many believe an equipment spark may have ignited dust or gasses in the air. Of those killed, only 74 were classified as ‘‘Americans.’’

The resulting public outcry brought Congressional action, culminating in the creation of the U.S. Bureau of Mines in 1910. That year, the first mine foreman certification examinations were required.

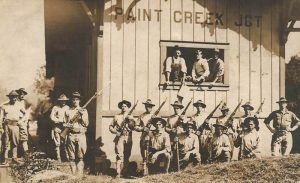

In 1913, when Union miners struck Paint Creek, the governor proclaimed martial law after miners and mine guards clashed.

Large-scale surface mining began in 1914, with the development of huge shovels and draglines, allowing easier removal of rock and soil.

By 1917, the amount of coal produced had increased to 89.4 million tons. The number of mine employees kept pace with production, growing from 3,701 in 1880 to nearly 90,000 in 1917.

By the 1920s, underground work was revolutionized by the mobile loading machine, which organized formerly independent miners into supervised crews.

Before the Great Depression of the 1930s, more than 90% of the miners in southern West Virginia lived in company-owned towns that did not have civic institutions. Combined with numerous work-related grievances among miners, labor-capital relations in the coalfields were frequently strained. Generally, the pivotal issue was the recognition of the United Mine Workers of America as the bargaining agent for the miners. In addition to being opposed to unions, coal operators attempted to control labor costs within a constantly changing market.

Company towns were especially plentiful in southern West Virginia. In 1930, there were an estimated 465 coal company towns in West Virginia, with the majority in the southern counties of Raleigh, Fayette, McDowell, Logan, and Mingo.

Some of the most famous strike episodes in the history of the American coal industry occurred in West Virginia between 1910 and 1933, including the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1912-13; the Mine War of 1920-21, which included the March on Logan, the Battle of Blair Mountain, and the Matewan Massacre; and the Monongalia-Fairmont coalfield wars, which occurred between 1927 and 1931.

In these disputes, the coal companies resorted to every means, legal and otherwise, to break the strikes and prevent unionization. Generally, the government sided with the companies. This period ended with the Great Depression, as the coal industry buckled in the general collapse of the American economy.

It was not until the Franklin Roosevelt era that the federal government intervened to help the miners. The National Industrial Recovery Act was passed in 1933 to help industry and labor during the Depression, established an eight-hour day and minimum wage provision, granted workers the right to organize unions, and provided incentives for companies to abandon costly and unpopular paternalistic policies. Afterward, coal companies sold off the miners’ houses and ceased to provide community services, such as education, police, and fire protection, and abandoned many of the mining towns altogether.

Since the 1930s, the union has been a powerful force in procuring welfare, retirement, and many other benefits for the miners.

After 1936, mechanization went forward rapidly, with shuttle cars, long trains, conveyor belts, and large mining machinery coming into common use.

During the Depression and World War II, the coal industry introduced more labor-saving machinery. Miners resisted mechanization, but this was overcome when the union negotiated an agreement with the operators. The union accepted a reduction in the number of workers but ensured increased productivity would result in higher pay and shorter working hours for the miners who remained.

Over the next half-century, tonnage and employment increased dramatically. By 1950, some 125,000 West Virginia coal miners lived and worked in more than 500 company towns built to house them and their families. There are no company-owned towns today, although remnants of many survive as privately owned communities.

By the early 1950s, a machine known as the continuous miner consolidated all of the basic steps in the mining process into one machine operation. The declining number of workers the increasingly automated coal industry required directly affected thousands of West Virginia families.

By the 1970s, mining was revolutionized again by the introduction of computerized longwall mining, which sheared coal off sections hundreds of feet long onto conveyor belts.

In 1950, there were 127,000 coal miners, but by the end of the 20th century, that number had plummeted to under 18,000 even though coal production reached record highs. Correspondingly, the high unemployment forced many miners to leave the state to search for employment elsewhere.

By the end of the 20th century, ever-larger earth-moving machines decapitated entire mountains in the controversial practice of mountaintop removal.

As the capital requirements increased, hundreds of coal companies either dissolved or were consolidated into much larger corporations. By the end of the 20th century, a handful of major multinational corporations dominated the industry. Production grew under these conditions. In 1997, West Virginia reached a peak coal production of more than 180 million tons.

Over the years, West Virginia has furnished our nation with the finest bituminous coal found anywhere.

At the same time, the West Virginia coal industry exhibits a sense of responsibility – social, health, safety, and environmental – that is unmatched anywhere in the world. More people are killed in farming accidents in the U.S. today than in coal mining accidents.

Today, 25% of coal mined is shipped to foreign markets where it is primarily used in steel manufacturing. The domestic steel industry uses another 15%. The remaining coal mined in West Virginia is used to generate electric power.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Ludlow and the Colorado Coalfield War

Mining on the American Frontier