By Sue Moore

William J. McGrew might have been a hero, but unfortunately, he turned out to be a scalawag. Born in 1844 in either Claiborne or Copiah County, Mississippi, his roots were Old Alabama, but his destiny was an early grave in unholy ground in Texas.

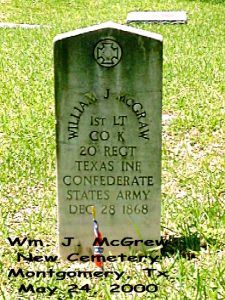

He joined the Porter’s Guards, Co. H of the 4th Texas Infantry C.S.A., at the beginning of the Civil War in Montgomery, Texas, but was discharged in 1861 as being disabled. He was only 17 at the time. He returned home to Montgomery in Montgomery County, Texas, to eventually become a lieutenant of the home guard, Co. K, 20th Texas Regiment, basically assigned to duty in Texas and the Indian Territory.

Remaining in Porter’s Guards of Hood’s famous Texas Brigade were the Cartwright brothers of Montgomery’s Bear Bend. Unfortunately, E. W. “Ras” Cartwright became the first casualty of the company. As the group was being shipped to the Virginia battlefields, the train stopped at Holly Springs, Mississippi. “Ras,” six feet six, borrowed a sword and was impersonating an officer in order to impress the Southern belles gathered on the platform.

Evidently, he was enjoying himself so much that he was the last man to leap aboard the moving train. Somehow the sword caused him to trip and fall beneath the train, severing both legs and resulting in his death. The Cartwrights’ bad fortune continued when brother James G. W. Cartwright was killed in the bloody Wilderness Campaign in Virginia, and brother Lemuel, the eldest, was wounded and lost an arm in the last major conflict before Appomattox. Their unit was devastated, and of the 143 men of Porter’s Guards, Hood’s Texas Brigade, only nine remained to surrender with Lee in April of 1865. However, the survivors of the Cartwright family would soon cross paths with the McGrew-Oliver clan.

Following the war in 1867, William J. McGrew/McGraw was appointed county attorney during Reconstruction. His reputation among town folks was “a Republican appointee by day, a KKK by night, and a horse thief in between,” according to Montgomery County Historical Society’s Choir Invisible. Added to his list of misdeeds were the actions of John P. and Robert O. Oliver, his younger half-brothers, teenagers who maddened the town folks by riding their horses into business establishments, shooting up the town, robbing, and stealing.

These boys had inherited a terrible legacy. Their father and William McGrew’s stepfather, Egbert O. “Eg” Oliver, had been shot down in 1853 in old Montgomery when the boys were small children. From the Autauga Citizen, Prattville, Autauga County, Alabama, issue of Thursday, Oct. 20, 1853:

“Death of an Outlaw: The Galveston Civilian has a letter dated Montgomery, Texas, October 1st, in which the writer says: A sad occurrence took place in our (town) between seven and eight o’clock. A man, well known in this section of the country, if not in others, named Eg Oliver, was shot from his horse on the public square. He had been arrested by the sheriff of which was for an assault with intent to kill a fellow named Lang in this county. It being the greatest charge on which the sheriff was authorized to arrest him, he brought him to our town and delivered him to our sheriff, who committed him to jail in default of bail. About a week before court began here he broke out and was then supposed left.

But during court, he was seen several times in this vicinity, and one night went to the house of our sheriff and called him up, but would not let him approach near enough to arrest him. Yesterday, while most of our citizens were at dinner, he rode into the square, galloped about it, and then rode off again, in defiance to all. He was pursued by the sheriff and several citizens but eluded the pursuit, and last night just at dark came into town again, threatening, as I am informed, to burn the jail. In attempting to arrest him for the purpose of recommitting him, he refused to surrender, and while in the act, as was supposed from his action (it was dark) of shooting upon those gathered around him, he was shot down, fell from his horse and died immediately. Who committed the deed, can never be known, as there were several shots fired at the same time. Thus perished a man, who, by his reckless and lawless course of life has been a horror to some, and respected by but few. May the memory of his many errors be buried with him. He has left a wife and two small children who have been compelled to flee from him, and seek protection under the roof of strangers.”

To make matters worse, William’s real father had been an outlaw in his own right. William “Red Bill” McGrew and his cousin William “Black Bill” McGrew, in their early twenties, had killed two teenage boys in Sumter County, Alabama in 1835. In May, Alabama Governor John Gayle put out an $800 bounty for their apprehension. From the Commercial Register of Mobile:

“Wanted – A Proclamation – On or about the first day of April of the present year [1835], William McGrew and William P. McGrew, in the county of Sumter [Alabama] murdered a couple of boys in the foulest manner, and under the most shocking and aggravated circumstances. The oldest of the lads was 16 or 17 years of age and his little brother about 11 or 12. Their name was Kemp. They were peaceably at work, earning a subsistence for the indigent family to which they belonged, having given no offense or provocation whatsoever, when they were cruelly shot down at the same time, in a very wantonness of deliberate and cold-blooded murder.”

Notices of the reward appeared in Mobile, New Orleans, and even in Texas. Soon another reward of three thousand dollars was raised by the citizens of Sumter and Marengo. Published in Mobile, New Orleans and in the Brazoria, Texas Republican 24 October 1835 was this description of culprits:

“William P. McGrew (“Black Bill”) is about twenty-four years of age, hair a little dark, fair skin and blue eyes; mild, and retiring look when sober; six feet high. William McGrew, (“Red Bill”) the cousin of the other, is about 21 years old, red hair, fair skin, eyes between gray and blue, six feet high, down look and forbidding countenance. Both addicted to intemperance.”

“Black Bill” McGrew fled to Texas, to a place “about 125 miles from Nacogdoches” where bounty hunters from Alabama ” handed a letter, perhaps from some authority in Texas to a man there by the name of Bowie with the expectation of getting his assistance in the taking of McGrew; but he being the friend of McGrew showed him the letter. The party in pursuit of McGrew immediately became alarmed and fled,” according to the Voice of Sumter paper, Nov. 6, 1837. Eventually, McGrew was betrayed by a man posing as a friend and turned over to the three bounty hunters. He was returned to Alabama where he escaped from the Mobile jail and was subsequently recaptured by the sheriff in Little Rock, Arkansas. As he was being returned to Alabama, he created such a commotion on board the steamboat trying to escape that the Captain was obliged to put him and the sheriff off at Vicksburg. He was then shackled and the sheriff and a contingent of men delivered him for trial in Sumter County. Tried for murder, he received a $500 fine and one year for manslaughter since evidence proved the Kemp boys had readied guns in an ambush position. In addition, the Kemp boys’ mother, who was the only eyewitness, told at least three different stories to different people and did not fare well under cross-examination. Yet within the year, “Black Bill” died from his prison experience.

Because the people of the town did not want to bury the outlaws in their existing cemetery, they were buried outside the consecrated ground in an area simply called the “New Cemetery.” The first to be buried here, McGrew is the only one who has a marker, but his half-brothers, the Olivers, are said to be buried beside him. Photo courtesy Sue Moore

Ironically, his name “William” had once been an honorable one, passed down from “Black Bill’s” father, William McGrew, Territorial Representative, Colonel and commandant of the 15th Regiment Militia, Clarke County, Alabama, and a hero of the Creek War, killed by Indians at Bashi Creek in Alabama in 1813. “Bill” was only two years old when his father was ambushed, and his mother Nancy Hainsworth McGrew Phillips did not maintain such an honorable family reputation. In the Voice of Sumter, August 9, 1836, she was denounced by Regulators, as a “Jezebel” for harboring mixed Indians and borderers among her clan, and for aiding and abetting the Kemp-McGrew feud. The article by Louis C. Gaines called for her to be driven from the country, but she said she would “die on the grit.” Evidently, she did choose to return to Texas. She had been listed in the failed Wavell’s colony in Texas in 1830, causing her to remain in Alabama, but in 1850 she was in Leon County, Texas, whether by choice or force is unknown.

“Red Bill” McGrew was arrested in St. Stephens, Washington County, Alabama in June of 1836. He was arraigned, pled not guilty, but evidently was never tried, probably due to the inconsistencies brought out in his cousin’s trial. The Voice of Sumter reported his court appearance:

“Thursday being a fair day, our town was crowded too with persons anxious to witness the interesting trial of McGrew, which has received double interest from its notoriety. About 10 o’clock, the accused, a young man of fine personal appearance, was brought to the bar, and a great rush was made for the Courthouse to secure an opportunity of witnessing the event. But a small number of the multitude could crowd in the house, and the yard was thronged with spectators on tiptoe to listen to the trial.” Evidently “Red Bill” could no longer remain in Alabama, so he sought a new home.

Economic depression occurred in Alabama beginning with the Specie Circular (an executive order issued by President Jackson requiring payment for the purchase of public lands be made exclusively in gold or silver), and by the early 1840’s the cotton market was in shambles. The McGrews had once been very influential and wealthy planters. The patriarch of the family, John McGrew, had arrived on the Tombigbee River above Mobile in 1779, settling in what would become old Washington and Clarke counties. He had survived the English, the Spanish, and the Indians, carving out the largest holdings in the area. The chiefs of the Choctaw Nation had deeded him 1500 acres of the best river land because “in his kindness, he had saved them from famine.” He ran more than 1,000 cattle on his plantation. The infamous “Bills” were his grandsons. With the economic crash, Caroline McGrew, “Red Bill’s” mother, moved her family to Claiborne County, Mississippi, after seeing her once-fine plantation sold for taxes after the death of her husband, John Jr., in 1842 in Texas. Bill and his family evidently accompanied her at this time, eventually succumbing to the greener and fresher pastures of Texas in the 1840s.

How “Red Bill” ended his days is uncertain, but McGrew cousins who lived in old Milam, Sabine County, Texas, passed down a story of two men who arrived sometime in the mid-to-late 1840s at their home. One was a McGrew cousin they called “Red,” and he was wounded. The men had saddlebags full of gold which they were taken to Mississippi. During the night, “Red” crept out, buried the gold, and returned to bed to die before morning. The gold was never found, and he was buried north of the house. His mother’s estate papers in 1853 in Claiborne County, Mississippi, revealed that Bill was dead in Texas, survived by several children, including a son William – William J. McGrew who would come to no good end in Montgomery in a few short years at the hands of a group of vigilantes led by the Cartwright family.

Ironically, the Cartwrights and McGrews knew each other back in old Washington County, Alabama. Thomas Peter Cartwright, the patriarch of the family, had served on juries with the McGrews. He was a Methodist minister, and he and his wife Elizabeth Shaw, had eleven children, all were born there. Old John McGrew and his sons John Flood McGrew and Colonel William McGrew were judges and representatives of that area to the Mississippi Territorial Legislature. Flood McGrew had been appointed by President John Adams as a member of the Territorial Council of five men who served as a virtual Senate of the Mississippi Territory. So the families certainly knew each other. When they moved to Texas, the Cartwrights also became influential in county government, with old Peter Cartwright becoming a Justice of the Peace in 1836 and Samuel Cartwright becoming sheriff of Montgomery County. For an unknown reason, Samuel resigned in 1866. Records do not show how or when William J. McGrew became the county attorney, but records indicate he was in office in 1867.

About this time, according to Robin Montgomery’s History of Montgomery County, Jesse James had camped at McGraw’s crossing of the San Jacinto River for a few weeks. When the gang departed, they left behind Charles “Tex” Brown, a Yankee sympathizer, with whom Jesse had grown weary. “Tex,” also believed to be a murderer and deserter from Wheeler’s Cavalry, then fell in with the McGrew-Oliver clan. He was described by J. W. DeForest in Harper’s Weekly, December, 1868, as “Twenty-three or twenty-five years of age, of medium height, slender, sinewy, and agile, with a dark complexion, piercing black eyes, and a jaw disfigured by a pistol shot, and an expression of brutal ferocity.”

What caused the shootout in late December of 1868 is not recorded in the county records, but two old citizens of Montgomery County, Mrs. W.C. Cameron, and Mr. Buck Martin recounted the following, according to Narcissa Boulware of the Montgomery County Times:

“When they (the gang) stole a fine horse from the Cartwrights and came into town to rob the stores and head out on ‘a scout’ for Mexico, a mob was formed at Bear Bend where the Gaffords, Cartwrights, and others who came in after the men, lived.” According to Montgomery’s History, “Finally the citizenry had had enough, and led by the old family of Cartwrights from Bear Bend, they engaged in a bloody shootout with the outlaws in Montgomery which ranged over several blocks. At the end of the battle, all four desperadoes were dead and placed on Mrs. Oliver’s porch.” Sadly, Cameron and Martin recounted the deaths of one of the boys, “Bob Oliver the youngest, was scarcely 16 years old at the time. When the shooting started, he ran to Mrs. Chilton’s house. The mob followed, promised not to shoot him if he would come out. Someone killed him with a Bowie knife. He ran back into the house before he died. Here he died under a bed. The bloodstains can still be seen on the floor.”

Another citizen and a local judge, Nathaniel Hart Davis, recorded the bloody event on page 33 of his journal,

“McGrew-Oliver Killing of Dec. 28, 1868 – On the 28th of December in the forenoon four men, Wm McGrew Esq. County Atty. for the last two years and his two half-brothers, John and Bob Oliver of this town and “Charles Brown” of Cokesbury, S. Carolina alias “Texas Brown” of whom an account is given in Harper’s Monthly of Decr. 1868 were shot to death here (Montgomery) by some ten to 20 or thereabouts, men of this town and vicinity. If the people or society can be said to act in necessary self-defense in the destruction of lawless desperados then I am of the option that this was such a case- a few others hereabouts may be nearly as bad as they-or some of them-one, May made a narrow escape. McGrew for a young man was a moral disgrace to the legal profession as he was to the office he filled. I did not recommend him to the Police Court – the appointing tribunal. After I started for Miss. and Tenn. in Jany., I learned that he was in the crowd that took the Negro at court and that he and others had disguised themselves in the Post Office that night. On my return, I found quite a change for the better in Montgomery. It is now rather an orderly quiet place. And the general expression is that much good was done in the killing of Dec. 28. There may be some, for reasons best known to themselves who regret the death of McGrew. One white single female to whom he paid marked attention both before and since his marriage, manifests a fondness for his memory and a sorrow at his loss and continues to talk long after with a silly sentimentality-so says gossip. I heard not talk but believe it true – Miss E.A.”

William McGrew’s grave marker in Montgormy’s New Cemetery, photo courtesy Photo Robert L. “Dan” McGrew.

The desperadoes were not buried in the consecrated ground of the old cemetery, but rather outside the gates in what would become Montgomery’s New Cemetery. There is a CSA marker on Lt. William McGrew/McGraw’s grave, but his young stepbrothers, buried near him lie unmarked. The only good thing said of William McGrew was recorded in the Houston Times, picked up by the Texas News, dateline January 23, 1869, “Tragic affair at Montgomery County. Death of William McGraw, county attorney. Mr. Brown of San Antonio and two brothers named Oliver and William McGraw was in no way connected with the difficulty. He was trying to prevent the parties from using their pistols.”

©Sue Moore, January 2005, updated December 2020.

About the Author: Sue Moore is a retired English teacher and descendant of the Alabama McGrew family. Ms. Moore has written several articles for genealogical/historical magazines and books and is a winner of the American Association of State and Local History awards. She has been researching her family history for 50 years.

Thanks Sue for a great article.

Also See: