Salt Lake City is well situated in the valley with gently rising ground to the foothills. The streets were wide and had running water in ditches through them. The buildings were mostly of logs, and in the center of the town was what might be termed a fort. The log cabins were built in a hollow square, enclosing two acres of ground, and at different intervals were gates; this no doubt being for defense in time of Indian troubles. However, the Mormons became friends of most of the Indians in that country and any Indian you met always said, “Mormonee, Mormonee, heap good Mormon.”

We hired teams to take us to the Lake, about 20 miles away. The water is so impregnated with salt you could wade out to your armpits and then be raised right off your feet. One can walk along through the water without sinking any deeper, and a nap on the surface is not an impossibility. The water is very clear, so clear you can see the pebbles in the bottom at 20 feet. Along the shore was tons of salt, just win-rows of it two or three feet deep. We spent the day there, and on the return trip, stopped at a good camping place, where we refreshed ourselves with a few hours sleep, and then proceeded on our way to camp, arriving about sunrise the next day.

On Sundays, we heard Brigham Young preach. They held services in what they called their Tabernacle. It was made by planting posts in the ground, with poles across, and then brush on top, enough to make good shade. Seats were made of rough sawed lumber and would seat about a thousand. The pulpit was also made of the same rough material, no pains being taken to plane the boards.

During the first twenty minutes of the sermon, Brigham Young lectured them roundly on things to do and not to do, something on this line: “Some of you hang around the emigrant wagons and fool your time away, and by and by, tithing day will come and you won’t have a cent to pay your tithing, and as for the emigrant, so long as they are here, obey our laws and regulations they are welcome to stay, but, when they don’t they can go to hell and be damned. We don’t care for them anyway; look at this pulpit. My new vest is worn out already on these rough boards. Some of you might think I am swearing, but I am not, for when I swear, I swear in the name of the Lord, therefore this is not swearing.” Maybe it wasn’t swearing, but it sounded much like cursing. However he could say what he pleased to his people, and they come home from church mightily pleased that someone had caught it, and never taking any of the lectures for themselves.

A party of us thought we should like to prospect in the Wasatch Mountains, so ten of us left about 10:00 o’clock at night, quietly, as we didn’t want the Mormons to know anything of our intentions. We went up to the little Cotton Wood Canyon, reaching the mouth of the canyon about daylight. At the entrance we saw two men on horseback about half a mile distant, one on each side of the canyon, watching us. We traveled hard all day and camped at night good and tired. The majority turned back the next morning, and about a quarter of a mile away found a campfire still burning, but, no one in sight. Whoever followed us evidently thought we had turned back, and they did also. We were out five or six days, following up the creek to its source, in fact, went clear to the summit of the mountain, but, we ran out of grub and for three days had nothing to eat but chipmunks, at least what little there was left after shooting them with a rifle. We saw tracks of larger game, possibly elk, but none of us had ever seen any elk, and so did not know their tracks. Since being in California, and familiar with elk tracks I think there must have been elk in that country. Our prospecting didn’t amount to anything, as we knew nothing of prospecting. We might not have been sure of gold had we seen it lying loose in the ground. Since that time, the Emmas mine and other rich mines have been worked and millions taken right out of the ground we passed over at the mouth of the canyon. The boys of our crowd met us with a packhorse loaded with food, and you can imagine how the food disappeared, after being without for three or four days. While on the summit of the mountains we had a snowstorm, and this in September.

The Mormons were all fond of dancing, and fortunately, I was invited to several of the parties. Brigham Young always led off with the fairest in the assemblage, and it was always considered an honor to be chosen by Brother Brigham, as he was styled. In build, Brigham Young was very much like Theodore Roosevelt. He was a very good speaker, but no orator, but he shined as a leader. His people would do everything he proposed, and his control seemed to reign over them. I have been often asked how many wives he had, and all I have to judge by was the sleeping apartments. In walking past his place of residence I saw about seven or eight wagon bodies with covers on, all in a row ranged in his backyard and was told these were occupied by his wives. Across the square from where I boarded, were two more, and these I knew quite well.

The warm springs were there at that time, in an open plain and we all thoroughly enjoyed the bathing. One day there was a dozen of us enjoying our bath when along came a wagon, drove up to almost 30 paces of us and the driver asked if we didn’t know this was the ladies bath day. We told him we were entirely ignorant, and would immediately get into our clothes and give them full possession. Which we did. Many Mormons had been to California and returned with gold from the mines, and had it coined at Salt Lake into five-dollar gold pieces. On one side was printed the All-Seeing Eye and on the other side the Bee Hive. But, most of the currency consisted of shinplasters written on paper and signed by Brigham, and circulated only amongst themselves, for all things bought from emigrants was paid for in gold coin. The gold was soft, no alloy being used, so it lasted but a short time.

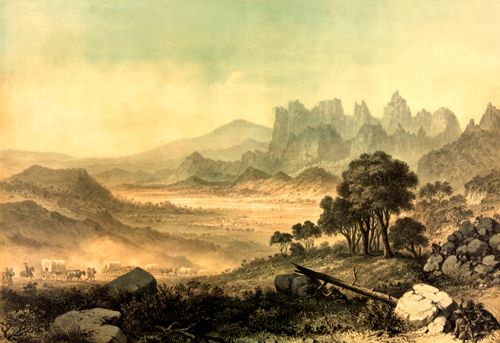

We commenced to think of leaving, and inquired about the best route out. The Mormons told us of the Donner Party being snowed in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and that it was too late now for us to undertake any route but the Southern route. This sounded plausible to us, but, there was a motive back of this that we didn’t comprehend. The Southern route was the Old Spanish Trail, and it was policy for them to have a traveled trail to the coast, rather than go back to the Mississippi or Missouri Rivers for supplies.

About the latter part of September, we started the organization of a company, and by the first of October we had gathered 105 wagons, and a Mormon guide, who claimed to know the road well, and he did prove to be competent. Our contract with the guide, Captain Jefferson Hunt, called for a $1,000 to Los Angeles, or $10.00 per wagon. As soon as the wagons were in readiness, the start was made on the first day of October, from a place called Provo, where we congregated, 50 miles from Salt Lake.

We were divided into seven divisions, each division had a captain, and a name coined to suit the fancy of the division. Some of them were “Bug Smashers,” “Buck Skins,” “Wolverine,” “Hawk Eye,” etc. The one to which I belonged was styled the “Jay Hawkers of Forty Nine,” the party that plays the prominent part in this narrative.

Every day we took turns leading the train as it was styled. That is, the division that led the train one day fell into the rear next day, for the leader always had the hardest work, for the road had to be broken. The first part of the journey was through the sagebrush and proved difficult traveling, and with such a large company we made but a few miles a day. The trail was over low rolling hills covered with scrub cedars, and somewhat sandy soil in places. The grass and water became scarcer every day, but, we managed fairly well until we passed Little Salt Lake, where three Mormons made their appearance on horseback. The leader and spokesman said his name was Barney Ward, and that he was an old mountaineer and plainsman and knew the country well, and by following his proposed route we could cut from 400-500 miles off our journey.

He had the road all mapped out and a diagram showing the camping places, about 15 miles between. Naturally, we fell into a discussion, for the road would terminate at the mines, instead of Los Angeles. Meeting after meeting was held, and all the advantages of the cut-off were discussed. In the meantime, we had reached what is now known as the Iron Mountain. I think that I, with one of the others, was the discoverer of this mountain of iron. After camping, we strolled up the mountain, and the rocks were noticeable for their weight and their positions. They lay in masses and had a metallic ring to them. I took one into camp, and showed it to a professor we had with us and he pronounced it iron.

We camped next at Mountain Meadows, a place that afterward became known as the scene of the Mountain Meadow Massacre of 1857. It takes too much space to give in detail all the horrors of this massacre, but, to sum it up, according to the best information obtainable, 120 lives were taken, and 17 children between the ages of two months and seven years, were spared from the butchery.

According to the evidence, the Mormons and the Indians divided the spoils, but, the Indians became dissatisfied with the division. After a lapse of 29 years, during which there was trial after trial, with no jury ever agreeing, John D. Lee was convicted. In the hearing, he said “there must be a victim, and I am selected as the victim. I studied for 30 years to make Brigham Young my pleasure, and see what I have come to. I have been sacrificed in a cowardly dastardly manner.” He was shot to death while seated on a rudely made coffin, on the same spot where occurred the massacre.

Almost a day out from Mountain Meadow, we came to the point where the road left the main trail. A halt was called, and Captain Hunt said those who wished to go with him could do so, and he would guide them to safety. The result was that out of the 105 wagons there were only seven that accompanied him. When we started on, Captain Hunt called out to us “boys if you undertake that route you will go to hell.”

I know now he knew whereof he spoke. He had had considerable desert experience, and we none. He realized these men who were leading were fakes, sent out by the Church for a purpose, but, to tell us so would mean the loss of his life. Brigham and the church wanted a short route to the Pacific Coast, and here was the opportunity of having that route prospected. Counting the toll in lives was a nominal consideration.

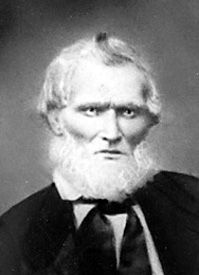

Captain Jefferson Hunt

But, the train moved on, notwithstanding Captain Hunt telling us where we would land. After two days’ travel, we came to a bluff, seemingly a thousand feet to the bottom, and straight up and down. A small stream flowed at the bottom, and by using ropes and buckets we could get enough for camp use, using it sparingly. The oxen had to go without, and after a couple of days prospecting, a greater part of the train turned back to take up Captain Hunt’s trail. But, the “Jay Hawkers of ’49” said they had started on this trail and would follow it or leave their bones on the way.

After reconnoitering we found, by taking a circuitous route, we could get the whole division, with the exception of two wagons. Others followed, but the “Jay Hawkers” took the lead, and kept it, and followed as direct a western course as possible, turning aside for the low passes in the mountains. There was no solid range of mountains to cross, but rather, a series of broken ranges where we crossed the passes at quite high altitudes. Thus, week after week passed with scarcely any grass, and the oxen were becoming weaker from day to day. The distances were so great between water places and when water was found, it seemed impossible to use it, being so blackish.

On one occasion we had gone five days without water, but through a kind Providence on the third night, snow came. About two or three inches fell, but before the ground was barely covered we were all out gathering the snow to melt, and before the storm had passed we had ample supply for ourselves and our oxen. No doubt this is what saved many of us, for we never reached water for two days more. It became a cause of anxiety, whether we would ever reach the next watering place or not. It became the custom toward the last to send out men to prospect for water, and if water was found smoke was made, as in this desert country smoke could be seen a great distance.

From day to day our cattle became weaker and weaker, and our provisions were getting low. So we were put on short allowance. Finally, the teams could pull no further, many had already died, so the wagons were abandoned and pack saddles made on the oxen.

On Christmas day, 1849, we were all busy making pack-saddles, and cooking the scanty supply of flour into little biscuits, or crackers, as they were perfectly hard. We were divided into twos, from eight men to two men mess, and each one had his share allotted to him. We had a half dozen of the little crackers, about three or four spoonfuls of rice, and about as much dried apples, and this ended the bill of fare, which must last until we reached settlements.

California seemed a long way off. We did not know where we were, but, I know we were much further off than we realized. The proposition now became a single one, for we just had to subsist on the oxen, and they had become so poor there was little or no nourishment in their flesh, as they were dying then from starvation.

As soon as an ox fell he was butchered, everything saved, especially the blood. We did not know where we were and we realized that the strictest economy must prevail. We even boiled the hide and it became partially tender. When we left Salt Lake City, we had two teams of four yoke of oxen to each, and only eight men, with what we considered ample provisions. Captain Jefferson Hunt had told us of the distance to Los Angeles, and if we had remained with him we would have had abundance. When we killed an ox we cut the meat into strips, and dried it over a fire, during the night, so it would be ready to pack the next day. We found little patches of greasewood, the only thing that grew in the desert, and this was of a very scrubby variety at best. It grew not more than two feet high, of the size of a finger, still, by searching diligently we could secure enough to answer our needs in camp.

Here is where the Reverend J. W. Brier and his family came up to us and wanted to travel with us. At first, we objected, as we didn’t want to be encumbered with any women, but, we hadn’t the heart to refuse. So they joined the “Jay Hawkers”, and the little woman proved to be as plucky and brave as any woman that ever crossed the plains, either before or since. They had three small boys, about six or eight years old. When the smallest got too tired tramping he was placed on the back of an ox for a change.

There were others who came to our camp, one was a company of Georgians, about 15 of them. The next day we saw snow on the mountains in the distance, and we know if we could reach the pass through the mountains we would find water, so we started straight for it. But, the Georgians hugged the foot of the mountain, in hopes of finding water in the canyon. They found no water, but, did find a silver mine, of almost pure silver. I saw a piece they melted and made a gunsight of. Thousand and thousands of dollars have been spent trying to find the gunsight lead. Governor Lore of Nevada fitted out several expeditions to try to find it, but it has never been located. I was offered all kinds of money in California to go back and hunt for it, but, I never had the least inclination to accept.

Captain Townshend who seemed to be the head man of the Georgia company, took the company through on another route. They packed their provisions on their backs and were better supplied than we were, as they still had some flour of which they gave a portion to the Brier family. They succeeded in getting through Walkers Pass, on to the head of Kern River, then into San Joaquin Valley and to Chowchilla River, where they were nearly all murdered by the Indians.

I believe there were but two who escaped. Another party of eleven men passed who thought they could make it by packing on their backs enough to last them. They had killed their oxen, dried the meat and packed what they could, and out of the eleven there was but two to finish the trip, the others having died, in a pile. These two would have died also had it not been they disagreed on the route to travel and stole away in the night.

In 1864, I was traveling down Owens River Valley, below Owens Lake, and at a place now known as Indian Wells there came a man in from the Slate Range of Mountains. In the conversation, he told me that some of his party in prospecting had come across the remains of nine men all together behind a little barricade of brush. They had probably built a wind break and had died right there from thirst. I made him promise that he would see the remains properly buried upon his return.

Speaking of thirst, there is no punishment that has any comparison. It is the most agonizing suffering possible and the feeling is indescribable. Our tongues would be swollen, our lips crack, and a crust would form on our tongue and roof of the mouth that could not be removed. The body seemed to be dried through and through, and there wouldn’t be a drop of moisture in the mouth.

So day by day we pursued our way, our cattle and ourselves growing weaker and weaker. The outlook was gloomy, and often when we killed a steer we looked forward to the marrow found in the bones. But in breaking the bones often there would be nothing there but a little bloody substance, and I suppose our bones were much in the same condition, as we had become as starved as they were.

Another party, called the Bennett party, tried a little different route from ours. They struck off South from us on the other side of the mountain. I didn’t know the number in the party, but, there were two families of Bennetts, and the Arcans, and each had a wife, but no children. There may have been ten or a dozen altogether. They called a halt and sent two of their number, William Lewis Manly, and John Rogers, on to the settlements for supplies and pack animals. They thought the trip there and back wouldn’t take more than two weeks, but, they were gone five, and those behind gave up all hope and resigned themselves to their fate. About this time the boys returned, and when within a few hundred yards of camp found one lying dead. They saw no sign of life in the camp and gave the rest up for dead. A few minutes later they heard a feeble cry, “there they are, the boys, I knew they would come back,” the women said, and such rejoicing as there was.

It became a great task now to save our oxen. We had used all the iron shoes and had to depend upon moccasins for the oxen as well as for ourselves. We made them from the hides, but some of the country was so rough with rock, sharp as flint, that every day new moccasins had to be put on the oxen.

Sand dunes nearby Old Stovepipe Wells in Death Valley National Park, California. Photo by Dave Alexander.

We finally reached Death Valley, where we lost two men, Fish and Isham, who were of the Brier party. One of our party went out hunting water, Deacon Richards by name. He found a spring, just about dusk. He gave the usual sign and from that time up until midnight the company came staggering in, but in the morning we found two missing. We took water and started back and found them dead within a hundred yards of each other. We named the spring Providence Spring, and it retains its name to this day. It was always so when water was found, the strongest came in first, and the weakest was last. Those first in returned to help the others, and so long as they kept their courage there was hope, but, just as soon as they gave up a little they wouldn’t last long.

I remember one incident relating to this and that was the case of Captain Asa Haines. He was quite elderly compared with the rest of us, probably 60 years of age. He would remark, “Boys, if I only had the corn that my hogs at home are rooting in the mud I would consider it the greatest luxury imaginable,” and then would cry like a baby. A few days later he said to us, “Boys, I feel that I can’t go any further and I’ll have to leave you”. I knew then that he would die soon, and told my mess-mate, Bill Rude, that Captain Haines would not live until morning. We had each saved two or three of our little biscuits and a couple of spoonfuls of rice. I told Bill I was willing to give all I had to Asa Haines if he would. So we took the last morsel we had saved, made a kind of stew of it, and carried this to Haines. He said, “Boys, you have saved my life”, and we knew we had. It did us more good, yes ten times over, than if we had eaten it ourselves.

We all thought a great deal of the Captain, and I have never felt so satisfied in my life with a deed, as I did in knowing that I was the means of helping to save a valuable life. He remained in California a short time and returned to Illinois, where he lived not more than three miles from my father’s house. Father wrote me that Captain Haines often came to the house and told him that his son saved his life in California. Bill Rude was also a neighbor of his and thought a great deal of him. He felt that we could get to California and a few spoonfuls of food to us was nothing compared to a human life.

From Providence Springs we crossed the range of mountains, and going down the other side, one of the best oxen went over the cliff and broke his back. We had to stop and make him into jerky. It seemed only a short distance across to the snow mountains that loomed up in sight, but the remainder of that day and the next went by before we came to water, which has since been known as Indian Wells, owing to the water being in holes or wells.

At this camp, William Lewis Manly and John Rogers saw our light and thought us Indians, until they heard my voice and they then knew we were “Jay Hawkers”. They came into camp and were made welcome to all we had. We struck a broad plain trail that we knew must lead to settlements and we resolved to follow it no matter where it leads. It took a southerly direction instead of a westerly, but we were bound to stay with the trail. We found out afterward that this trail was made by the Owen River Indians, or Paiutes, who made raids into the large ranches of California and ran off hundreds of head of horses at a single drive. The Spaniards were afraid to follow, as they would be outnumbered. A year or so afterward I stayed overnight at Williams Ranch, where there were thousands and thousands of cattle and horses, and the owner told me that he had made a treaty with the chief of the Indians, presenting him with a fine horse and silver-mounted saddle, and the Indians always knew his brand after that and never troubled him.

The next morning, William Manly and John Rogers took the trail and hurried, as they were anxious to make the trip and get back to their company. We traveled two more days, and then the trail ran right into an immense desert and we could scarcely see the mountains beyond. If the trail had not led that way we would never have thought of facing such a dreary outlook. In after years, I found this was the Mohave Desert. Going on we found an immense lot of bones all along the trial. After two days of travel, we came to a spring right in the middle of the desert. There was quite a patch of willows growing around the water, and plenty of water for our use, although it ran but a few rods and then sank into the sand. While here, we killed another ox and prepared the meat for jerky.

It proved to be a long way to the mountains, for we were three days and nights making the trip. Our progress was slow, and there was much suffering. Many could travel but a few hundred yards at a time, and so the weaker ones were hours behind in getting into camp. When water was found the smoke was made and this would put new life and energy into the weak ones. One man named Robinson had become so weak we had to put him on a poor little mule we had. He said in the morning he couldn’t make it, but we thought he could on the mule. When within 30-40 steps of the campfire he fell off. We tried to assist him, but, he begged to be left alone, saying he would come when rested. About 15 minutes later, as he hadn’t come in, we went to get him and found him dead. The next morning we buried him as best we could, for the ground was hard and rocky and we only had our knives to dig with, and our hands to throw out the dirt. At this same camp a Frenchman, his name not known, became insane and after wandering away was captured by the Indians and kept a slave for 14 years. He was finally rescued by a United States surveying party and brought to the settlements.

At this watering-place, the trail seemed to be obliterated and from here we ascended a long hill or divide, and after crossing saw a brook with running water, the first we had seen for months. It looked good to us, and we concluded it must empty into the Pacific Ocean, which was correct, for this proved to be the headwaters of the Santa Clara River that empties into the ocean near San Buena Ventura. Here, we found timber and signs of game, – the tracks of a grizzly bear where we had crossed the creek. Three of us started after him and followed the tracks till dark. We camped on the tracks, intending to follow him the next morning. I stood watch the first half of the night, and the other two were to take the last half. I called them and then crawled under the blanket, and in a moment I was asleep, but, the boys never got up. In the morning when I awoke I could hardly get my breath, so I threw back the blanket and found the snow fully four inches deep. This ended the bear hunt, and when we got back to camp we found the oxen had stampeded and had run away beyond all recovery. This left us with one ox, and we would not have had him, but someone had happened to be leading him. This was all we had left out of 16 we left Salt Lake with, besides two horses. It was only our division that lost the cattle. The others were further behind and did not get into the stampede. We didn’t mind much, as we felt we were now in a game country and could live anyway, but, we didn’t find game so plentiful.

The next game we came across, was an old mare and two colts, a yearling and a two-year-old. Ed Doty and Bill Rude happened to be ahead and got all three of them. We camped right there and built a fire and went to eat. I thought I had never eaten anything that tasted as good. They had a little fat on them and that was what tasted so good to us. We ate the old mare up that night and made jerky of the colts to pack along. As the Reverend Brier was well supplied with oxen, he kindly permitted us to pack one or two of his oxen.

Two or three days later some of the boys killed a deer, and some of us stayed back to dry the meat, and the rest went on. Among those that stayed was old man Gould, as we called him, and he and I tried to sleep together. We had only one single blanket between us and he wouldn’t pull his boots off. He said if he had to die he wanted to die with his boots on. He seemed a little off in his mind, and by the way, there were two in our party who never did get entirely in their right minds again. The next day brought us out into the most beautiful valley I ever saw in all my life, Paradise, in fact. It was covered with thousands of cattle feeding, and they looked so fat and sleek, I never had anything that impressed me as that sight did, I felt as though I could stand there and gaze on it forever.

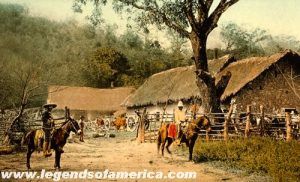

After coming off the desert the contrast was beyond all description. The boys that were ahead of us, when they came to the cattle, shot three or four. It seemed to them that each man could eat a steer. The Spaniards heard the shooting and didn’t know what to make of it, but gathered such arms and other implements as they had, and came out to where the boys were. They did not know then what they were, as the boys were so emaciated and ragged. In fact, our boys didn’t pay much attention to them, for they were too busy skinning and tearing off the fat parts of the meat and eating it just as it was. They hadn’t taken time to start a fire to cook it.

It just happened that we had a man with us that had been in the Mexican War, and he knew little Spanish. His name was Tom Shannon. When the Spaniards saw the condition of the company they said, “Buena Mericanas”, and told them to come on down to the ranch and they would kill an animal for them there, but, the boys wouldn’t take any chances, and they began to load themselves with beef. The Spaniards told them that was too much hard work. The boys marched down to the ranch about four miles distant, and when they arrived, found a bullock already slaughtered. The boys went at once to eating roasted meat and eating all they could stuff. This came near killing some of them, as it was too rich for their weakened condition. We were lucky in being a day behind and profited by their experience. We ate sparingly at first, a little at a time. I know the first night at the ranch I got up two or three times in the night and roasted me a piece of beef. In fact, I couldn’t sleep from thinking how good the meat was. It did taste good, though our stomachs craved fat more than anything else, even castor oil tasted fine. This ranch lies on the Santa Clara River, and is called San Franciscita, and was owned by Del Vule.

We certainly were well treated. They gave us everything they had, such as beef, corn, milk, wheat, and chili peppers, and offered us money, but, of course, we could not accept money, as they had been so kind. Some of the boys had money and offered to pay for what had been furnished us, but, they wouldn’t take a cent. In fact, they were the most hospitable people I ever was among where the country was first settled, but, that state of affairs changed after a few years.

After being at this ranch for a day or two, we thought we would have a bath in that beautiful stream of water. Upon removing my clothes I was actually frightened. I found I was nothing but a skeleton. My thighs were not larger than my arm, and the knee joints were like knots on a limb, and on my hip bone, the skin was calloused as thick as sole leather and just as hard, caused by lying on the hard ground and rocks. We were all of us in pitiful condition, hardly fit subjects for a picture show. After recuperating for a few days at the ranch we began to try to make arrangements for getting on to the mines. Some went one way and some another, and some came up by water from San Pedro, which was a very wise thing to do.

But, we all did not have the money to do that, and I was one of that number, so, instead of starting up the Coast via San Buena Ventura, I went to Los Angeles to take a start from there. I was only there three or four days when I found an opportunity to come along with a couple of men who were buying up pack mules. I could travel with them if I could furnish my own saddle and help drive the mules. So I paid four dollars for a saddle tree, or what the Spaniards call a busta. This left me with only a dollar. Everything went well enough until we arrived at Santa Barbara. I had been in the habit of taking the mules out to graze every morning as soon as it was light enough, so at Santa Barbara I did the same thing, but it happened to be a cold stormy morning, and rain poured down. I had no coat, just a woolen shirt, and no vest, and the mules were very hard to manage. They wanted to travel with the storm in spite of all I could do. Time went on and I kept getting colder and colder. Ten o’clock came, and no relief party was in sight as had been the custom up to that time, but, I supposed it was a little too stormy for them to turn out. And the longer I waited and the more I thought of it, the madder I got. I gave the mules a good scare, and they went a flying, and I turned and broke for shelter. By this time we had drifted with the storm about four miles, and I had to face the storm going back. When I entered the dining room where the pair were smoking their pipes by a good warm fire, the first greeting I got was “Where are those mules gone to?” Then I let loose on them and don’t know what I told them, but, it wasn’t anything very pretty. There was a large butcher knife lying on the table nearby and I kept my eye on that and was careful to stand near it, but, they were great cowards, both of them, and did not try taking revenge at that time. They certainly were brutal taking advantage of a poor helpless boy and imposing on him in that manner.

This left me stranded in Santa Barbara with a single dollar, so in order to make my dollar go as far as I could I would buy me a piece of beef and a few crackers, or hardtack, and go out to where there was a big log burning just on the outskirts of the town. I kept this up for a few days until an old Spanish woman, who had seen me making my trips out to the old log, finally hailed me and asked, “Why don’t you come here and eat?” Of course, I could not understand a word she said, but she just made me understand by bringing out her frijoles, tortillas, meat and coffee, and putting them before me. I understood what she meant then and she made it plain that she wanted me to come every day and for every meal. She seemed to have plenty, and evidently, she could see by my looks that I needed fattening. I hadn’t gained any flesh as yet and my cheekbones stood out quite prominently. I spent most of my time trying to find some work, but, there was no building going on, and as I had no knowledge of Spanish, there were no openings for work. I believe there was but one American there and he kept a grocery store, but, he had nothing for me to do. Prospects looked gloomy, and I was 2,000 miles from home, with no money. I had suffered everything but death to get there and was still some 500-600 miles from my destination, the mines. How to reach the mines was a problem.

I knew I could walk but, had no money to help me on the way. While in this quandary some emigrant wagons drove in and camped at the old log where I first cooked my meat. The teams all belonged to a man called Dallas. There were four of them and they proved to be a part of our original train of 105 wagons and Old Dallas was one of the parties who had turned back and taken up Captain Hunt’s trail. I had a partial acquaintance with him, to begin with, but, I knew him better by his reputation and that wasn’t the best. I thought if I could make some arrangements with him whereby I could reach the mines, I didn’t care much if he did get the best of the bargain. After talking with him we made an agreement that he should board me at the price of twelve dollars a week, and give me the privilege of riding in the wagon, as I was still too weak to attempt heavy walking, and I wanted to be in good condition to work when I reached the mines. I was to pay for my passage when I got work in the mines. Everything was satisfactory, and we started. About two days out, one of the drivers said he had a lame back, Dallas came to me and asked me to take the man’s place, saying he would make it alright with me. For five weeks I drove the team through wet grass up to my waist in many places. If the sun happened to be out my clothes would hardly be dry before noon. This was an every morning occurrence, and still, the man’s back continued to be lame, for it was much easier riding in the wagon than walking and driving the team.

At one place a tree had fallen across the road, and had been partially cut away, but, when I attempted to pass, the tree stuck in the end gate of the wagon. There was but one thing to do and that was to cut the tree off, and while I was busy doing this “Old Dallas” came up and started his abuse. He stopped at nothing in his tirade, and I stood it as long as I could, finally starting for him, telling him he had gone too far already. He ran around the wagon, keeping the wagon between us, and by this time others of the party came up and quiet was restored again. This ended my driving team, for I told him I wouldn’t drive another step for him.

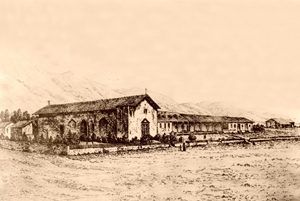

We finally reached and passed through San Jose, about March 1850. The Legislature was in session here, and at this time, San Jose was nothing but a Mexican settlement of adobe shanties, dives and all manner of gambling dens were running full force. Santa Clara Street ran to Third, and after that, you ran into the mustard grass. In fact three or four blocks from the center of town in any direction you got into the mustard, which was so thick and high it was well-nigh impassable, except in the trails made by cattle.

Going towards San Jose Mission we passed two houses, the first was occupied by Mr. Vestal, about a mile from town, and in the second house, Jim Murphy lived. Just beyond the crossing of Coyote Creek some Alvisos lived near the foothills on the east side of the valley. On the road, where Milpitas now is, there was nothing but, a horse corral, and in Milpitas, I built the first cabin in 1852.

Passing the Mission we came into the Livermore Valley, and Livermore himself lived there at the time and offered me work at $200 a month and board. He had a building he wanted done, but, we passed on. We reached the San Joaquin Plains, and they looked very beautiful, for at this time they were covered with wildflowers, and were level as far as the eye could see. The plains resembled the Illinois prairies more than anything I had seen on the whole trip. There were bands of wild horses or mustangs as they were called, and herds and herds of elk and antelope – there seemed to be no limit to them.

I never saw so much game in such a space of country, excepting the buffalo on the plains. It seemed as if there was wild game enough to feed a nation. Speaking of game, California was the best country I ever saw; one could go anywhere in the state, and find all the game he wished.

We crossed the San Joaquin River at Bounsall’s ferry, just where the railroad crosses now. The old man’s heart was nearly broken when he found he had to pay a fee of ten dollars a wagon and a dollar a yoke for the oxen in order to ferry; but, it was either pay or stay on that side of the river. Fifteen miles brought us to Stockton, and on the day we arrived I had been just one year on the road, with the exception of six weeks I spent in Salt Lake City. Everything was lively in Stockton. Buildings of all kinds were being rushed, and lumber was selling for three hundred dollars a thousand, at that time all the lumber came around the Horn, and carpenters’ wages were an ounce or sixteen dollars a day. There were many cloth houses, tents of all kinds, and shacks of every description. Some of the better houses cost $150,000 and over. Freighting charges were from six to ten cents a pound to the mines. People were flocking to the mines, some walking with their blankets strapped on their backs; some were in stages; some on mule back; but all were trying to reach the gold district. Many came back and reported the whole thing as a hoax and a failure.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated June 2021.

About the Article: This article was excerpted from Lorenzo Stephens’s book, Life Sketches of a Jayhawker of ’49, published in 1916. However, it is not verbatim, as it has been edited, truncated, and updated for the modern reader.

Lorenzo Dow Stephens, Pioneer

Lorenzo Dow Stephens (1827-1921) – Death Valley pioneer, California ’49er, gold prospector, cattleman, sheepman, adventurer, entrepreneur, railroad investor, businessman, farmer, author, and historian.

Lorenzo was born near Hackettstown, New Jersey on September 29, 1827, to Richard and Eleanor Addis Stephens, the youngest of five children. Just before the Black Hawk War, the family moved from New Jersey to Illinois, where his father built the first frame house in what would become Canton, Illinois. In about 1832, the region became much disturbed from the Black Hawk War, and the family moved to Ohio. After about six, years, they returned to Illinois, settling near Galesburg. Lorenzo was reared on a farm and acquired agricultural knowledge, but, was also taught the carpenter trade under his father’s able instructions.

He was 21 years old when the news of gold discovery arrived from California. He was anxious to try his fortune in the mines and joined an Illinois party bound for the Pacific Coast. On March 28, 1849, the expedition started on its long and fatal journey. Finding that navigating in such large numbers was slowing them down, they divided into small groups. Lorenzo’s group of men, mostly from the Knox County, Illinois area called themselves “The Jayhawkers”. He would later write of his adventures in a book called Life Sketches of a Jayhawker of ’49, published in 1916, where he described the trials and tribulations of the overland journey west, including Brigham Young’s sermons at the Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, and the deaths of many along the trail. Because it was October when the group left Salt Lake City, they chose to take a southern route, which placed them in Death Valley. Lorenzo Dow Stephens was the last surviving member of the Jayhawker group and the only person of that first group of pioneers that crossed Death Valley to author a book telling of those days in the desert. His memoirs continue through the 1860s describing prospecting on the Merced River, farming in the Santa Clara Valley, cattle drives from San Bernardino and San Diego, and taking part in the 1862 British Columbia gold rush.

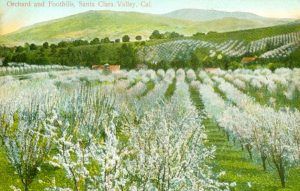

Santa Clara Valley, California

Lorenzo married Julia Ludlum in San Francisco, California on December 25, 1867, and the couple would have two children. Stephens didn’t make his fortune in mining, rather, he was among the first Californians to capitalize on the great need for cattle in the north, buying herds in southern California and driving them to sell to the gold miners of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and in San Francisco. He purchased over 2,000 acres in the San Joaquin Valley for a ranch to base his cattle and was an early investor in the lumbering and railroading ventures in the Santa Cruz Mountains. He also manufactured windmills and farmed in the Santa Clara Valley. He and his family settled in the Santa Clara Valley, where he remained for the rest of his life. However, he never gave up his adventurous nature, traveling to the goldfields Nevada, Idaho, Oregon, British Columbia, as well as visiting Hawaii, and the great Klondike Gold Rush in Alaska in 1899.

Lorenzo Dow Stephens died on February 10, 1921, and was buried in Oak Hill Memorial Park, San Jose, California.

The San Jose Mercury newspaper did a feature article about his life, which stated in part:

“The last of the Jayhawkers, Lorenzo Dow Stephens, whose figure on the streets of San Jose for many years was a familiar one, has passed away. For seventy years he was known and very generally beloved in this county. He was the last of the Jayhawkers, the first party of white people to invade Death Valley. It seems incredible that Mr. Stephens left his Illinois home seventy two years ago in 1849 to make the trek across the continent by oxen transportation, the only means of interstate travel at that time. Mr. Stephens was a pioneer of pioneers. He was one of a few men that could speak personally of the influx of seekers for wealth in the gold days of ’49. No more picturesque figure could be found in this county than Lorenzo Dow Stephens, a splendid relic of the old school of Americans.”

Also See:

Crossing the Great Plains in Ox-Wagons