By Edward Sylvester Ellis in 1892

Until the year 1851, the vast plains to the eastward side of the Rocky Mountains were regarded as Indian territories, over which numerous tribes roamed at will from Texas and Mexico to the British possessions to the north.

The discovery of gold in California, in 1849, drew the eyes of the civilized world to the Pacific Coast, and a tide of emigration set in that direction, the like of which this country had never seen before. The ships that made the tempestuous passage around Cape Horn were crowded to overflowing with men eager to face every peril for the sake of digging the yellow particles from the mountains and river beds.

While these lines of travel were crowded, thousands more crossed the continent by the plains or overland route, which was filled with perils. The emigrants spent weeks and months, their wagons winding slowly across the prairies, fording streams, climbing mountains, toiling through ravines, deluged with rain, sleet and snow, shivering with cold or fainting with heat, and in continual danger from Indians. Many a train that left Independence, Missouri, fully equipped and armed, and full of high hopes, never lived to catch the gleam of the far Pacific. If they survived starvation and the rigor of the climate, they were overwhelmed, perhaps, in some lonely glen by the fierce warriors, and their whitening bones were left to tell their fate to the crowds following in their footsteps, and compelled to face the same perils and possibly to meet the same fate.

The tide of emigration across the plains made necessary a treaty with various tribes, by which a broad highway was opened to California, and the Indians were restricted within certain boundaries. The government agreed to give the tribes $50,000 annually for 15 years in payment for the privilege granted to emigrants to cross the plains without molestation.

This treaty assigned as boundaries to the Cheyenne and Arapaho, the larger part of the present State of Colorado, while the Crow and Sioux were to occupy the land traversed by the Powder River route to Montana. However, some years later, gold and silver were discovered in Colorado upon the Indian lands, and hundreds of settlers crowded in, as usual with no regard for the rights of the Indians. When these intruders had taken up most of the lands, another treaty — The Treaty of Fort Wise — was made on February 18, 1861. The Indians agreed to give up an immense tract of territory and to confine themselves to a small district on both sides of the Arkansas River, and along the northern boundary of New Mexico. The government bound itself to protect them in these possessions, paying an annuity of $30,000 to each tribe for 15 years, and to furnish them with stock and agricultural implements.

No difficulties occurred between the white inhabitants of Colorado and the Indians until April 1864. During the summer of that year, some warriors began committing depredations and robberies upon the property of the settlers. Colonel John Chivington, commanding the troops at Denver, allowed a subordinate officer to lead a detachment of soldiers to punish the Indians for their acts. He attacked the Cheyenne village of Cedar Bluffs, killed 26, wounded 30, and divided the plunder among his men. Hostilities and fighting continued until autumn, but the Indians wanted peace and applied to Major Edward Wynkoop, commander of Fort Lyon, Colorado to negotiate a treaty to secure it. That officer ordered the Indians to gather about the fort, assuring them of protection.

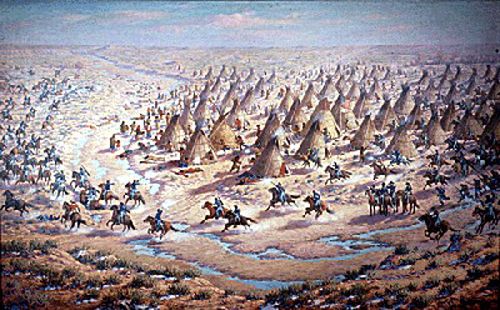

In response to this command and guarantee, 500 men, women, and children collected at the post. Colonel Chivington then attacked and slaughtered them without mercy. This horrible crime, known as the Sand Creek Massacre, was committed November 29, 1864. Inevitably, a war with these tribes followed, drawing 8,000 men from the forces in the field to suppress the insurrection, and costing the country 30 million dollars. During the campaign of 1865, less than 20 Indians were killed. The attempt to obtain peace by this means was as futile as with the Seminole tribe, nearly 30 years before.

Commissioners were appointed in autumn of 1865, to secure a council with the tribes and end, if possible, the war. In October of that year, the commissioners met the chiefs of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other tribes at the mouth of the Little Arkansas River, and induced them to give up their reservation upon the Arkansas River, and accept another in the State of Kansas, with the privilege of ranging over the plains formerly owned by them.

The Senate later amended this treaty to exclude the tribes entirely from Kansas, leaving them nothing but their hunting privileges on the unsettled plains. Nevertheless, the southern tribes strictly observed the treaty through the year 1866.

The Sioux, to the north, had driven the Crow into Montana and occupied the wide range of territory originally assigned to both. The territories to the south had become populous, and rumors of rich mines in Montana attracted emigration in that direction across their lands. This narrowed the rich hunting grounds to the valley, from the north of which flowed the Powder River. The annuities from the government having ceased, it was important that the remnant of the Indians‘ hunting ranges should remain intact, for they afforded their only means of subsistence.

Orders were issued by the commanding officers of the Military Departments of the Missouri and of the Platte, to establish several military posts along the new route of travel to Montana. The orders were given June 15, 1866, to garrison Forts Reno and Phil Kearny in present-day Wyoming, and C.F. Smith in Montana. The Indians warned the troops from the first that this occupation of their territory would be resisted; however, no heed was paid to the threat, and fighting continued through the summer and autumn. On December 21, 1866, a wagon train attended by an escort was sent a short distance from Fort Phil Kearny, to procure lumber. They were attacked by Indians and Brevet Lieutenant Colonel W. T. Fetterman was ordered out with 49 men to the rescue of the wagon train. The entire company, including its commander, was assailed and massacred by the Indians. The event is known today as the Fetterman Massacre.

Great apprehension now prevailed that war would be kindled along the line of the Union Pacific Railroad. General George Crook, commanding from Omaha, Nebraska, forbade the sale of arms and ammunition to the Indians within the limits under his command. This deepened the resentment of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, for, without ammunition, they could not hunt for food.

The troops on the Powder River route were exasperated and alarmed by the Sioux and Cheyenne, who would not listen to any proposition until the troops were withdrawn. The memory of the Sand Creek Massacre still burned in the hearts of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche and Apache. They had been driven from the rich lands of Colorado and left only the poor privilege of ranging the plains for the fast disappearing buffalo and other game, and now this privilege was made worthless by the order forbidding the sales of arms and ammunition, which was promulgated in January at the Arkansas River posts also. Threats of a general Indian war in the spring were uttered by the leading chiefs and warriors.

The American forces were under the command of Lieutenant General William T. Sherman, of the Military Division of the Missouri River. This division was made into three departments: Dakota, on the north, commanded by General Alfred H. Terry; the Platte River, in the middle, commanded by General Christopher C. Augur; and that of Missouri River, to the south, commanded by General Winfred S. Hancock.

A violent storm raged on that day and prevented the conference. The following day it was learned that about 1500 Cheyenne were encamped at a village on the Pawnee Fork, Kansas. On the 13th, General Hancock rode toward the Indian encampment and was met by the chiefs, who begged him to come no nearer with his soldiers as they were afraid of a repetition of the scenes of Sand Creek. Thus, did the shame of one officer throw its baleful shadow over the spotless fame of another.

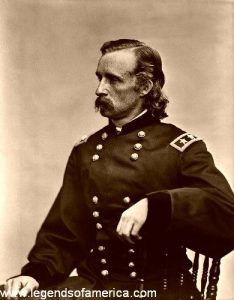

General Hancock advanced, however, and the warriors fled with their families. In their flight they destroyed several stations, killing the guards and taking away the property. Learning of these acts, Hancock burned the village, consisting of 300 lodges, and property to the amount of $100,000. He pushed westward, and hearing of constant attacks by the hostiles upon the Smoky Hill Trail, on the line of the Union Pacific Railroad, he sent General George A. Custer with a force of 400 men in that direction.

Custer met Oglala Sioux War leader, Pawnee Killer, and sought a friendly understanding with him, but without success. The attacks by the Indians continued, and Custer assumed the offensive, rarely succeeding in bringing about an engagement with them. Near Fort Wallace, Kansas, 500 Indians attacked the wagon train, and a fierce engagement followed. The wagon train got through with a loss of 12 men. Soon after this occurrence, on June 26th, General Custer was recalled from the region.

General Hancock continued his expedition and held a number of important conferences with chiefs who professed a desire for peace if it could be had on equitable terms. Hancock returned to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in August and was succeeded by General Philip Sheridan.

The Indians were much exasperated by the burning of the village on Pawnee Fork, and continued their depredations during the summer. The operations on the Union Pacific Railroad were much slowed down. Surveyors and workmen were often waylaid and murdered, and stock and materials were driven off or destroyed. Stages and express trains were robbed, stations burned, settlements attacked, and a wild predatory warfare carried on.

In August 1867, a freight train from Omaha, Nebraska was thrown off the track near Plum Creek by obstructions placed on the rails by Indians. The cars and merchandise were burned, and all the employees on the train, except one, were killed. General Augur sent a detachment of troops to the scene. They were joined by a band of friendly Pawnee, and in a fight with 500 Sioux, killed 60 of them.

Most of General Augur’s forces, numbering about 2,000, had been sent under General John Gibbon to the region about the sources of the Powder and Yellowstone Rivers, where the northern tribes were engaged in hostilities. On August 2nd, a band of woodcutters at Fort Phil Kearny, attended by an escort of forty soldiers and some fifty citizens, was attacked by an overwhelming force of Indians. A desperate fight followed, lasting three hours, when the whites were saved by the arrival of two companies of Federal troops with a howitzer, who drove off the warriors, inflicting a loss of more than 50 killed and a large number wounded.

The operations against these Indians accomplished nothing. General Sheridan declared that fifty of them could checkmate 3,000 soldiers, and recommended peaceful negotiations as the only means of putting an end to the lamentable state of affairs.

Congress passed an act in July, “to establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes,” which provided for the appointment of commissioners with a view to the following objectives:

1. To remove, if possible, the causes of the war.

2. To secure, as far as practicable, our frontier settlements, and the safe building of the railways looking to the Pacific.

3. To suggest or inaugurate some plan for the civilization of those Indians.

The commissioners selected were: N. G. Taylor, J. B. Henderson, Lieutenant General William T. Sherman, Brevet Major General W. S. Harney, John B. Sanderson, Brevet Major General Alfred H. Terry S. F. Tappan, and Brevet Major General C. C. Augur.

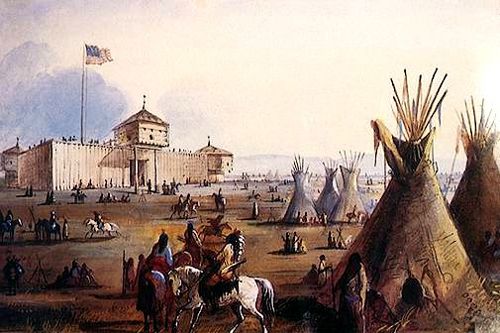

These commissioners organized at St. Louis, Missouri on August 6th, and set to work to obtain interviews with the chiefs of the hostile tribes. Runners were sent out to assure the Indians of the purposes of the commissioners, who visited various parts of the Military Division of the Missouri, taking evidence of the officers regarding the hostiles and the causes of the war, and completing arrangements for a great council of the northern hostile tribes at Fort Laramie, Wyoming September 13th, and of the southern tribes at Fort Larned, Kansas on the 13th of October.

It was found difficult to deal with the discontented Sioux, but, through the exertions of Swift Bear, a chief of the Brule Sioux, several tribes were represented at a meeting at North Platte in September, and something like a friendly disposition was shown. The Indians insisted before any talk was had that arms and ammunition should be promised them, and this was done by the commissioners. The meeting at Fort Laramie was postponed until November 1st, because it was impossible to get the northern Cheyenne and Sioux, who still kept up their hostilities on the Powder River route, to the post in time.

At the conference at Fort Larned, Kansas in October, the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache, who had not been engaged in any of the outrages upon the plains during the summer, were readily persuaded to meet the commissioners, and a satisfactory treaty was signed with them on October 20th. There was more difficulty with the southern Cheyenne and Arapaho, but they were finally induced to sign a joint treaty.

The commissioners then proceeded north to meet the tribes at Fort Laramie. A delegation of Crow awaited them at the post, but Chief Red Cloud, the mighty Sioux leader in the north, refused to have anything to do with the commissioners. He resisted all overtures, but, sent word to them that war would cease whenever the military garrisons were withdrawn from the Powder River Trail, and their hunting grounds left free from molestation. The commissioners, having no authority to make such withdrawal, succeeded in persuading Red Cloud to cease hostilities and to meet them the following spring or summer.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated June 2018.

About the Article & Author: This article was excerpted from Edward Sylvester Ellis’ book The Indian Wars of the United States: From the first settlement at Jamestown, in 1607, to the close of the great uprising of 1890-91, published by Cassell Publishing Co. in 1892. However, the article as it appears here is far from verbatim, as it has been heavily edited to provide additional clarification, remove references that are seen today as being derogatory, and updated for ease of the modern reader. Edward Sylvester Ellis (1840-1916) – Beginning his career as a school teacher, Ellis wrote his first successful book at the age of 20. In his early years, he wrote chiefly adventure fiction stories. Writing under dozens of pseudonyms, as well as his own name, he produced dozens of the popular “dime novels” of the time, as well as short stories and sketches for magazines and periodicals. Later in life, he began writing accounts of historical events and biographies and even dissertations on his view of life. His writing was so prolific and written under so many names, there is no complete listing of his works today.

Also See:

The Army In The Indian Wars, 1865-1890

Indian Wars, Battles & Massacres

Military Campaigns of the Indian Wars

Soldiers and Officers in American History